To address the complexity surrounding chronic unreduced shoulder dislocations and best practices for management.

Dr. Derrick Bark, Department of Research, Logan University, 1851 Schoettler Rd, Chesterfield, Missouri, United States. E-mail: derrick.bark@logan.edu

Introduction: Chronic unreduced shoulder dislocations (CUSDs) are rare with a prevalence of 0.10–0.18%, usually occurring after car crashes, falls, assaults, getting out of bed, and seizures. Management is often open reduction and fixation. Most cases have been reported in countries with inadequate resources and access to care often leading to misdiagnosis and poor management. We report a case of a patient with a CUSD presenting to a chiropractor within a federally qualified health center (FQHC).

Case Report: A 55-year-old, Spanish-speaking, uninsured, female was referred from her primary care provider to a chiropractor within a FQHC with right shoulder pain and reduced range of motion. The patient reported two incidences of right shoulder dislocation, the first being a closed reduction 1 year before presentation and the second occurring 5 months before presentation without any management. Radiographs demonstrated an unreduced right anterior shoulder dislocation. The patient was referred to an orthopedist who treats patients on a sliding scale according to their income.

Conclusion: Because the patient was uninsured and did not have the necessary financial resources, she was unable to receive a shoulder reduction. These barriers often contribute to the misdiagnosis and increase morbidity associated with this pathology. Exercise therapy was not advised out of concern for further structural damage and neurovascular compromise. The recommended management is with topical pain creams and corticosteroid injections as directed by their primary care. Clinicians working with this population should be aware of the diagnosis, both typical and urgent features, complications, and the standard of care in this condition.

Keywords: Chronic unreduced shoulder dislocation, federally qualified health center, Primary care physician

Shoulder dislocations account for roughly 50% of all joint dislocations [1], 95% being anterior dislocations [2, 3]. Multiple episodes of instability after initial dislocation occur in 7 out of 10 people [2]. The accepted definition for chronic unreduced shoulder dislocation (CUSD) is a shoulder joint that has remained dislocated for a minimum of 3 weeks or more [3, 4, 5, 6]. This presentation is rare with a prevalence of 0.10–0.18% [4, 5]. Often, CUSDs occur in those with epilepsy, cognitive disparities, advanced age, multiple traumas, and missed diagnoses likely secondary to limited access to health-care resources [7]. The body of literature on CUSD is sparse, including guidance for evaluation and management. In the US, the safety net population has the least accessible health-care resources. These disparities often lead to treatable conditions being neglected as seen with the majority of CUSDs. We present a rare case of a 55-year-old female seen by a chiropractor within a federally qualified health center (FQHC) with a CUSD. We review the current literature on CUSD epidemiology, evaluation, and management.

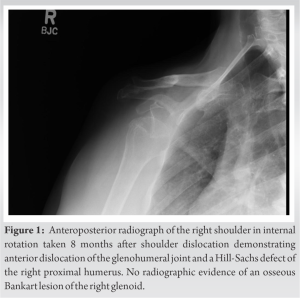

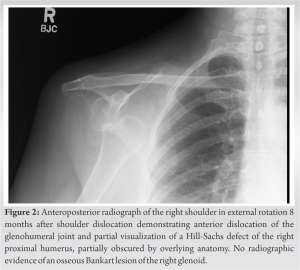

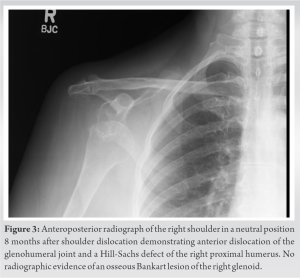

A 55-year-old female was referred by her Primary Care Physician (PCP) to the chiropractor for right shoulder pain. The patient was Spanish-speaking, required an interpreter, and was uninsured. The FQHC where she received all her care is an integrated community health center serving those that are part of the safety-net population, often living at or below the poverty level and under-insured. The patient had a history of right shoulder dislocation 1 year prior. At that time, she went to the emergency department and was treated with a closed reduction and sling. She followed up with her PCP who recommended wearing the sling for 1 week and was referred to an orthopedist. She did not follow through with the referral citing insurance status and financial barriers as the reason. Five months after the first shoulder dislocation, she rolled over in bed and dislocated the shoulder again. She opted not to seek care for 3 months then presented to her PCP who ordered updated radiographs and referred her to chiropractic. At examination, the patient had no neurovascular compromise. Inspection revealed right shoulder dislocation and deltoid atrophy. She was able to abduct the arm 110°. Passive range of motion was full and equal bilaterally.

This rare case of CUSD highlights the importance of recognizing an at-risk population, typical and urgent features, and appropriate management. Literature around CUSD is limited and in the form of case reports or case series which detail different approaches to treatment. The mean age of patients in these studies is 42–48 years of age [4, 5, 6]. There is no predominance in gender but sample sizes are limited. The average time of dislocation varies from 3 days to 10 years [4, 5, 6, 8]. The common causes of CUSD are crashes, falls, assaults, getting out of bed, and seizures [4, 5, 6]. Anterior dislocations remain the most common type typically from direct trauma with the arm forced into extension, abduction, and external rotation [3]. There are many associated pathologies clinicians should be aware of with shoulder dislocations, such as labral tears, that can reduce the height of the glenoid rim up to 80% [2]. The most common feature of anterior dislocation is Hill-Sachs lesions, found on the posterosuperior portion of the humerus, with a prevalence of 35–93% [2, 3]. Other structures often damaged are the rotator cuff muscles (RTC), glenohumeral ligaments, long head of the biceps, and the articular cartilage [2]. Radiographs utilizing anterior/posterior and lateral scapula or “Y” views should be taken pre- and post-reduction to assess for proper reduction [2]. Radiographs are helpful to evaluate the bony anatomy but provide minimal information on soft tissue. To further assess soft-tissue and other non-osseous structures, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended [2]. Magnetic resonance arthrogram is appropriate for chronic instability and detecting labral tears [2]. There are many limiting factors contributing to the unsuccessful reduction of a CUSD. Osseous contributors are displaced glenoid labrum, bony fragments, greater tuberosity fracture, and impacted humeral head into inferior lip of the glenoid [9]. Soft-tissue contributors are intra-articular fibrosis and scarring, ligament, and muscular contracture (long head of the biceps and the subscapularis tendon being the most common) [7, 9]. Recommendations report that 6 weeks post-CUSD, closed reduction is contraindicated, [9] due to the potential of iatrogenic fracture or neurovascular damage [10]. Neurovascular compromise is rare following acute dislocation but the risk increases with age and more aggressive attempts at closed reduction [10]. The axillary artery, just distal to the subscapular artery, is most commonly affected with resultant hemorrhage and ischemia from distal thrombosis [10]. Roughly, one-third of all patients confronted with a vascular complication have a history of previous joint dislocations or CUSD [10]. Brachial plexus injuries are associated with cases of arterial injury around 60% of the time [10]. A more common injury involves the axillary nerve with the mechanism being neuropraxic in nature [10]. Electromyography or nerve conduction study is appropriate tool for the assessment of nerve function [10]. Patient comorbidities as well as type and size of the lesion determine the most appropriate treatment procedure [10]. This includes the duration of the dislocation, associated injuries to the surrounding structures, hand dominance, previous operations, and functional demands of the patient [4, 5]. Treatment options include closed reduction, open reduction (with or without fixation), Bankart repair, hemiarthroplasty, reverse arthroplasty, full arthroplasty, conservative treatment, or no treatment [4, 5, 6]. Operative approaches show better outcomes compared to non-operative. When utilizing the ROWE score outcome measurement comparing the two groups, improvement in function and decrease in pain are larger in those who received operative management [6]. Non-operative approaches are utilized in those with limited functional demands, minimal discomfort, or with significant comorbidities [10]. The longer the glenohumeral joint remains dislocated, the higher likelihood of surgical intervention for appropriate reduction. The primary approach involves open reduction with fixation [5, 6]. Specific techniques are at the discretion of the surgeon and state of the patient’s condition. If the posterolateral humeral head defect involves <40% of the articular surface, and the dislocation is fewer than 6-month duration, the articular surface may often be preserved [8, 10]. Understanding the underlying condition, establishing need for emergent referral in the case of neurovascular compromise, and appropriate triage and management are necessary for positive outcomes. Limited information on the topic makes appropriate management and triage difficult. To provide the highest value care, these presentations and reviews are crucial for furthering our understanding and treatment.

The presentation of CUSD is rare in the US making assessment and management challenging. The improved access to care and available health-care resources in the US minimizes the likelihood of this condition. However, the safety-net population faces greater barriers to accessing these resources and receiving quality health care, often leading to misdiagnosis and lack of treatment. As seen in this case, the patient was unable to receive appropriate shoulder reduction due to being uninsured and financial barriers. These disparities contribute to the morbidity related to CUSD, underscoring the importance of a thorough evaluation and knowledge of resources available to each patient. When evaluating these patients consider more urgent features of neurovascular compromise, length and mechanism of dislocation, age, underlying comorbidities, and occupation. In this case, therapeutic exercise was not advised given length of dislocation and concern for further structural damage and neurovascular compromise. Topical pain creams and CSIs directed by a primary care provider were our treatment recommendations. Any suspicion of dislocation needs to be evaluated with radiographs pre- and post-reduction. Shoulder dislocations are often associated with other pathologies such as Hill-Sachs lesion, Rotator Cuff (RTC) tears, and labral tears adding to the complexity in management. For further assessment of soft-tissue and other non-osseous structures, MRI is appropriate. Orthopedic evaluation following diagnosis is crucial. Dislocation chronicity increases the possibility of adverse events, namely neurovascular compromise and iatrogenic fracture. Chronicity dictates management with closed or open reduction. The state of the articular surface guides surgical intervention. This presentation and review of the current literature are helpful in guiding appropriate management and to appreciate the continued need for updated literature on the topic.

CUSDs are rare and to date, there is little literature on appropriate initial assessment and treatment in a clinical setting, with misdiagnosis and health disparities often leading to chronicity and potential for serious adverse events. The goal of this case report was to provide a baseline understanding of the condition utilizing the most current and up-to-date literature to improve patient outcomes.

References

- 1.Kirtland S, Resnick D, Sartoris DJ, Pate D, Greenway G. Chronic unreduced dislocations of the glenohumeral joint: Imaging strategy and pathologic correlation. J Trauma 1988;28:1622-31. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Midtgaard KS, Bøe B, Lundgreen K, Wünsche B, Moatshe G. Anterior shoulder dislocation – Assessment and treatment. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2021;141:1074–7. [doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.20.0826]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.xPetrovecki V, Salopek D, Topic I, Marusic A. Chronic unreduced anterior shoulder dislocation: Application of anatomy to forensic identification. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2008;29:89-91. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rai AK, Bandebuche AR, Bansal D, Gupta D, Naidu A. Chronic unreduced anterior shoulder dislocation managed by latarjet procedure: A prospective study. Cureus 2022;14:e21769. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Babalola OR, Vrgoč G, Idowu O, Sindik J, Čoklo M, Marinović M, et al. Chronic unreduced shoulder dislocations: Experience in a developing country trauma Centre. Injury 2015;46 Suppl 6:S100-2. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goga IE. Chronic shoulder dislocations. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2003;12:446-50. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yanmiş I, Kömürcü M, Oğuz E, Başbozkurt M, Gür E. The role of arthroscopy in chronic anterior shoulder dislocation: Technique and early results. Arthroscopy 2003;19:1129-32. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flatow EL, Miller SR, Neer CS 2nd. Chronic anterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1993;2:2-10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Upasani T, Bhatnagar A, Mehta S. BBilateral neglected anterior shoulder dislocation with greater tuberosity fractures. J Orthop Case Rep 2016;6:53-6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verhaegen F, Smets I, Bosquet M, Brys P, Debeer P. Chronic anterior shoulder dislocation: Aspects of current management and potential complications. Acta Orthop Belg 2012;78:291-5. [Google Scholar]