Parosteal lipomas without malignant changes have good prognosis and no recurrence can be treated by surgical excision.

Dr. Naveen Sathiyaseelan, Department of Orthopaedics, Jhalawar Medical College, Jhalawar, Rajasthan, India. E-mail: spnaveen17@gmail.com

Introduction: Among all the primary bone tumors and all the type of lipomas, parosteal lipomas stand for <0.1% and 0.3%, respectively, which mostly consists of fully developed adipose tissue with or without a bony component. Patients with this tumor usually have bony lesions (59.2%), necessitating a differential diagnosis of malignant tumors.

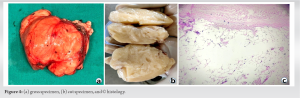

Case Report: Here, we analyze a case report of a 9-year-old boy, who developed a parosteal lipoma in the distal femur. A massive, well-defined, lobulated, mostly fat-intensity lesion of 10 cm by 6 cm by 8 cm was seen on an magnetic resonance imaging scan of the right distal femur. After the lump was removed, the pathologically reveals a parosteal lipoma without any malignant changes.

Conclusion: Finally, it should be noted that parosteal lipomas are less common neoplasias with no known malignant potential. Since these tumors can be removed with mild impact to nearby structures, the lower limb’s functionality is kept intact.

Keywords: Parosteal lipoma, distal femur, lipocytes, vastus medialis, case report.

Among all the primary bone tumors and all the type of lipomas, parosteal lipomas stands for <0.1% and 0.3%, respectively, which mostly consist of fully developed adipose tissue with or without a bony component [1]. The femur, proximal radius, humerus, tibia, clavicle, and pelvis are in which this tumor is most frequently found. The cortical bone is directly superimposed by parosteal lipoma. It is believed to develop from mesenchymal cells in the periosteum and similar histopathologic characteristics with the frequently occurring soft-tissue lipomas, and cytogenetic evidence points to a common histopathogenesis.

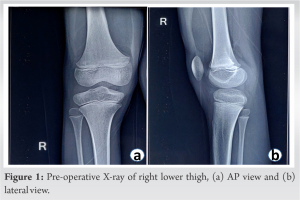

This report describes the case of a 9-year-old male who has been admitted on August 02, 2022, and who has a large mass on the anteromedial aspect of his right lower thigh over the past 6 months. The swelling had well-defined edges, was slow-growing, painless, soft, and non-tender; it was also immobile and not attached to the skin. He had no past trauma, no complaints of pain, and no movement limitations. Before, there had been no interventions. Both a drug history and a family history were absent. On clinical examination, an oval-shaped, elastic, immobile, and non-tender mass of approximately 10 cm × 6 cm was found on the right lower thigh anteromedial aspect. There was no sensory impairment in the right thigh of any kind. On X-ray of the right lower thigh, there was a shadow of poorly specific soft-tissue enlargement in the lower thigh anteromedially (Fig. 1a and b).

“Periosteal lipoma,” an uncommon kind of lipoma, was renamed to “Parosteal lipoma” to emphasize the tumor’s proximity to the bone but not necessarily its origin [2]. These lesions commonly appear on the long bone diaphyses in middle-aged people [3]. In addition, it has been demonstrated that the lesion can grow to the scapula, ribs, clavicle, thorax, pelvis, metatarsals, mandible, and skull [2]. These tumors usually have chondroid and/or osseous modulation, allowing subclassification into four different variants: (A) no ossification; (B) pedunculated exostosis; (C) sessile exostosis; and (D) patchy chondro-osseous modulation [3]. Parosteal lipoma manifests as a slow-growing, stationary mass over the bones that is not attached to the skin [4]. The radiographs shows as a well-defined radiolucent lesion next to the long bones and most of them are hyperostotic reactive, but 60% of them may also have additional possible bony alterations, such as cortical bending, smooth cortical erosions, or an osteochondroma [5]. Parosteal lipomas typically appear on computed tomography as a well-defined, lobulated, fatty mass adhering to the underlying bone. The link between the mass and the nearby bone can be assessed using the computed tomography images, which is helpful for surgical planning. On MRI, it is seen as a juxtacorticular mass with the same intensity as subcutaneous fat tissue, despite the pulse sequence. Because they are thin and devoid of post-contrast enhancement, on T1-weighted images of the lesion, it appears as low signal-intensity strands that correspond to fibrovascular strands can be distinguished from those of well-differentiated liposarcoma [6]. On T2-weighted images, more signal strength arise from the cartilaginous components, whereas they showed intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images [7]. A pale, yellowish multilobulated mass consists of mature adipocytes typically characterizes the lesion pathologically, well-encapsulated, and has a wider base of attachment to the underlying bone [5]. The adipocytes of the subcutaneous tissues and the fat cells of a parosteal lipoma are histochemically similar. Despite the possibility of modest cellular pleomorphism, there is currently no evidence to suggest that this tumor progresses to malignancy [3]. Total surgical excision is used to treat parosteal lipoma. In the presence of nerve entrapment, the tumor must be removed before serious muscular atrophy occurs. In addition, the nerve must be kept distinct from the parosteal lipoma and carefully protected during the surgical excision [8]. Rapid bone loss in a radiolucent lipoma should raise suspicions of malignant transformation [9]. The identity between the parosteal osteosarcomas and well-differentiated liposarcomas of soft tissue include their sluggish progression, localized aggressiveness, propensity for local recurrence, and rarity or the absence of metastasis if not dedifferentiated. Both tumors are well separated under the microscope and resemble normal tissue in many ways. Its two parts, the bone basis and peripheral fat, must be biopsied. The differential diagnosis of parosteal lipoma includes several malignancies.

This is a rare instance of parosteal lipoma without chondro-osseous involvement that has been well documented. These benign soft-tissue tumors have a good prognosis and “no” recurrence [4].

We suggest, the Parosteal Lipoma without Malignant changes can be excised surgically, and in the presence of nerve entrapment, the tumor must be removed before serious muscular atrophy occurs.

References

- 1.Aoki S, Kiyosawa T, Nakayama E, Inada C, Takabayashi Y, Sumi Y, et al. Large parosteal lipoma without periosteal changes. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2015;3:e287. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Greco M, Mazzocchi M, Ribuffo D, Dessy LA, Scuderi N. Parosteal lipoma. Report of 15 new cases and a review of the literature. Ann Ital Chir 2013;84:229-35. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miller MD, Ragsdale BD, Sweet DE. Parosteal lipomas: A new perspective. Pathology 1992;24:132-9. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pompili G, Tarico MS, Scrimali L, Scilletta A, Tamburino S, Curreri SW, Soma PF, Perotta R. A big parosteal lipoma of the thigh. Chirurgia 2011;24:107-10. Available from: https://www.minervamedica.it/en/journals/chirurgia/article.php?cod=R20Y2011N02A0107.[ Last access 15 March 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balani A, Sankhe A, Dedhia T, Bhuta M, Lakhotia N, Yeshwante J. Lump on back: A rare case of parosteal lipoma of scapula. Case Rep Radiol 2014;2014:169157. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphey MD, Johnson DL, Bhatia PS, Neff JR, Rosenthal HG, Walker CW. Parosteal lipoma: MR imaging characteristics. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1994;162:105-10. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy A, Williams J. Posterior interosseous nerve palsy caused by lipoma: A case report. Can J Plast Surg 2009;17:e42-4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goto T, Kojima T, Iijima T, Yokokura S, Motoi T, Kawano H, et al. Intraosseous lipoma: A clinical study of 12 patients. J Orthop Sci 2002;7:274-80. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larousserie F, Chen X, Ding Y, Kreshak J, Cocchi S, Huang X, et al. Parosteal osteoliposarcoma: A new bone tumor (from imaging to immunophenotype). Eur J Radiol 2013;82:2149-53. [Google Scholar]