Two-stage partial exchange with interim cemented liner could be an effective option for infected total hip arthroplasty.

Dr. Michelle Hilda Luk, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, 5th Floor, Professorial Block, Queen Mary Hospital, 102 Pok Fu Lam Road, Hong Kong. E-mail: michellehildaluk@gmail.com

Introduction: There is interest in partial exchange for infected total hip arthroplasty, as an alternative to complete removal of components in a traditional two-stage revision. Partial exchange avoids the difficulty of removing a well-fixed component and its associated bone loss.

Case Report: We report a case of a 61-year-old male patient with an infected total hip arthroplasty, who underwent a two-stage partial exchange, with retention of the well-fixed femoral stem, and an interim cemented liner. He had excellent function and no infection recurrence at 4 years of follow-up.

Conclusion: Two-stage partial exchange with interim cemented liner could be an effective option for infected total hip arthroplasty.

Keywords: Infection, prosthetic joint infection, two-stage revision, partial exchange, total hip arthroplasty, component retention.

Periprosthetic joint infection remains a dreaded complication and a substantial burden on the medical system, especially due to the increasing number of primary and revision total hip arthroplasties performed each year. Periprosthetic joint infection is associated with prolonged hospital stay, morbidity, and mortality [1, 2]. A two-stage revision is the accepted standard for periprosthetic joint infection in the United States [3, 4]. In the first stage, all components are completely removed, infected tissues are debrided, and a temporary antibiotic-loaded cement spacer is implanted. The patient is given intravenous antibiotics for about 6–12 weeks during this interim period until evidence of infection control, before the second stage reimplantation of a definitive total hip replacement. A systematic review by Lange et al. reported a 90% success rate of infection eradication with a two-stage approach [5]. There is increasing interest in the partial exchange of components, versus the traditional complete exchange in a two-stage approach. As many orthopedic surgeons may have experienced, a well-fixed implant can be a nightmare to remove. Partial exchange becomes an attractive option, avoiding the difficulty of removing a well-fixed component and its associated bone loss, and may reduce potential iatrogenic fracture. On the other hand, there may be concerns of the adequacy of infection clearance in a partial exchange revision. We report a patient with an infected total hip arthroplasty after multiple rounds of chemotherapy for rectal cancer, who underwent a two-stage partial exchange revision, with retention of the well-fixed femoral stem, who had excellent function and infection-free survival at 4 years of follow-up.

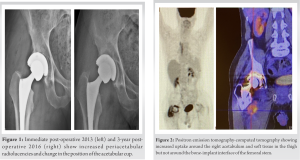

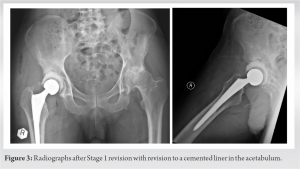

The patient is a 61-year-old gentleman with an infected right total hip arthroplasty for which he had a partial two-stage exchange performed. His primary total hip arthroplasty was performed in September 2013 for hip osteoarthritis. Pre-operatively, he complained of right hip pain for a few years, which limited him to walking with a stick. The primary right total hip arthroplasty components included a cementless acetabular shell and femoral stem, polyethylene liner, and a ceramic femoral head. He had a history of rectal cancer, with a rather turbulent course. A laparoscopic low anterior resection was performed in June 2014. He had further radiotherapy and chemotherapy in the United States. A left lateral segmentectomy was performed for pulmonary metastasis in October 2015 and underwent further rounds of chemotherapy. During chemotherapy, he had recurrent right hip wound swelling and discharging sinus, first noted in June 2015 (21 months after the initial total hip replacement), and he had two drainages performed by a general surgeon, without entry into the hip joint. The last incision and drainage were performed in March 2016. He was given a prolonged 3-month course of antibiotics. The organism isolated was staphylococcus aureus and the right hip swelling eventually improved. He was seen by orthopedics in July 2016. The C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were elevated to 121 mg/L (normal reference <5 mg/L) and 98 mm/h (normal reference 0–15 mm/h), respectively. A right hip aspiration was performed, which did not yield any growth from culture. Repeat radiographs showed acetabular component loosening with new radiolucencies in all three DeLee and Charnley zones and a change in the position (Fig. 1). The femoral component appeared to be well fixed. A positron emission tomography-computed tomography scan showed increased uptake mainly around the acetabulum (Fig. 2). A diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection was made on the basis of a discharging sinus [6]. The patient agreed to a two-stage revision with a partial exchange, with retention of the well-fixed femoral stem. The first-stage revision was performed on 22 August 2016. Intra-operatively, there was extensive fibrous tissue around the hip. The acetabular component was loose, and the femoral component was well fixed. Debridement of the infected tissues and irrigation were performed. The acetabular component and liner were removed. The femoral stem was retained. The fibrous tissue in the acetabulum was removed with reaming. A polyethylene liner was cemented with vancomycin antibiotic-loaded cement to the acetabulum, at the standard cup orientation of 45° abduction and 15° anteversion. The femoral head was exchanged to a metal femoral head. The reduction was stable and the patient was permitted for full weight-bearing walking post-operatively (Fig. 3).

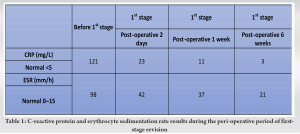

A diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection was made on the basis of a discharging sinus [6]. The patient agreed to a two-stage revision with a partial exchange, with retention of the well-fixed femoral stem. The first-stage revision was performed on 22 August 2016. Intra-operatively, there was extensive fibrous tissue around the hip. The acetabular component was loose, and the femoral component was well fixed. Debridement of the infected tissues and irrigation were performed. The acetabular component and liner were removed. The femoral stem was retained. The fibrous tissue in the acetabulum was removed with reaming. A polyethylene liner was cemented with vancomycin antibiotic-loaded cement to the acetabulum, at the standard cup orientation of 45° abduction and 15° anteversion. The femoral head was exchanged to a metal femoral head. The reduction was stable and the patient was permitted for full weight-bearing walking post-operatively (Fig. 3). Post-operatively, the wound was well and he had minimal pain. There was a downtrend of the inflammatory markers, CRP and ESR (Table 1).

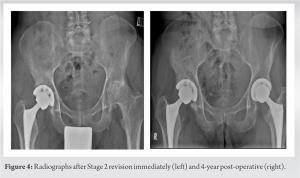

Post-operatively, the wound was well and he had minimal pain. There was a downtrend of the inflammatory markers, CRP and ESR (Table 1). The intra-operative specimens did not yield any growth from extended cultures. A second-stage revision was performed on 7 November 2016 (11 weeks from the first stage revision). Intra-operatively, there was no gross infection. The cemented liner and femoral head were removed. The acetabulum was further reamed and fitted with a new acetabular cementless component, polyethylene liner, and a metal femoral head (Fig. 4).

The intra-operative specimens did not yield any growth from extended cultures. A second-stage revision was performed on 7 November 2016 (11 weeks from the first stage revision). Intra-operatively, there was no gross infection. The cemented liner and femoral head were removed. The acetabulum was further reamed and fitted with a new acetabular cementless component, polyethylene liner, and a metal femoral head (Fig. 4). The post-operative period was uneventful. On his follow-up at 2 weeks post-operatively, he reported no right hip pain, and the wound was well. He also subsequently had left hip mechanical pain for which he had a left primary total hip arthroplasty in February 2016. At his last follow-up at more than 4-year post-operative, he had no hip pain or signs of infection. He had full Oxford (48 out of 48) and Harris hip scores (100 out of100) and had reported no limitation in walking tolerance.

The post-operative period was uneventful. On his follow-up at 2 weeks post-operatively, he reported no right hip pain, and the wound was well. He also subsequently had left hip mechanical pain for which he had a left primary total hip arthroplasty in February 2016. At his last follow-up at more than 4-year post-operative, he had no hip pain or signs of infection. He had full Oxford (48 out of 48) and Harris hip scores (100 out of100) and had reported no limitation in walking tolerance.

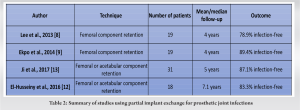

Attempts to remove a well-fixed component can be an arduous task and may result in undesired bone loss and make subsequent reconstruction difficult, with some even necessitating radical solutions such as a total femoral replacement [7]. Partial exchange becomes an attractive option, avoiding the difficulty of removing a well-fixed component and its associated bone loss and reducing the potential risk of iatrogenic fracture. In our patient, a partial two-stage exchange was performed with a first-stage temporary cemented liner and retention of the well-fixed femoral component. Once the infection was cleared, the patient underwent a second-stage revision to definitive components. It has been postulated that the successful osseointegration of the prosthesis, in the case of a well-fixed implant, can act as a barrier against infected tissue and joint fluid, sealing off the bone-prosthesis interface from the effective joint space [8]. Our patient had no hip pain, with full marks in both the Oxford and the Harris hip score and infection-free survival at 4 years of follow-up. The results are in agreement with good outcomes from other studies of two-stage partial exchanges. Ekpo et al. reported an 89% infection control rate for two-stage partial exchange for infected THA, and a mean Harris hip score of 68 out of 100. In comparison, our patient fared better with a Harris hip score of 100 [9]. A systematic review of 9 studies on 134 patients showed a 90% success rate for acetabular revision with femoral component retention. This review included both one-stage and two-stage revisions [10]. The results from partial two-stage revision also seem to be comparable to conventional complete two-stage revisions [11]. Other cohorts of partial implant retention are summarized in Table 2, with general good varying techniques. None of the studies used the technique in our study of a cemented liner as a temporary spacer. One-stage partial exchange may also be a reasonable option, with success rates of 83%–87% for infection eradication [10, 12]. The authors suggest to improve the success rate by local vancomycin powder and brushing the surface of retained implants to remove the biofilm as much as possible [13]. There is potential for more research to compare the outcomes between one-stage and two-stage partial exchange. In the past, a Girdlestone procedure or a static antibiotic-loaded cement spacer was used in the intervening period between the two stages, which rendered reimplantation in the second stage to be extremely difficult due to soft-tissue contractures. These procedures could lead to joint stiffness, limited mobility, and bedbound complications during this period. The arrival of articulating cement spacers was a welcome development, which permitted weight bearing, and patients were able to maintain a good range of movement of the hip while waiting for a second-stage reimplantation [14, 15]. Some authors may even consider it as a semi-permanent implant in selected patients due to its good function [16]. In our patient, after removing the acetabular component, we have cemented a liner to the acetabulum to articulate with an exchanged femoral head, instead of using an articulating spacer. Advantage to this method is that this gives excellent function and is similar to the metal-on-polyethylene articulation in a definitive total joint replacement. Furthermore, it may avoid possible complications of cement articulating spacers, such as spacer fracture, and avoid the difficulty of fashioning a spacer. A possible disadvantage to our method is the cost of replacing multiple components, as the liner and femoral head from the first stage will be exchanged again in the second definitive reimplantation. However, one may justify that there is an element of cost-saving in retaining the femoral implant, and there is potential to avoid the complications of an articulating cement spacer as mentioned above.

With evolving evidence, partial exchange may become a new standard for infected total hip arthroplasty with the advantages of avoiding substantial bone loss and subsequent reconstruction. The interim cemented liner could be an effective alternative for an articulating cement spacer in the first stage.

Two-stage partial exchange with interim cemented liner could be an effective option for infected total hip arthroplasty.

References

- 1.Shahi A, Tan TL, Chen AF, Maltenfort MG, Parvizi J. In-hospital mortality in patients with periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:948-52.e1. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gundtoft PH, Pedersen AB, Varnum C, Overgaard S. Increased mortality after prosthetic joint infection in primary THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017;475:2623-31. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berend KR, Lombardi AV Jr., Morris MJ, Bergeson AG, Adams JB, Sneller MA. Two-stage treatment of hip periprosthetic joint infection is associated with a high rate of infection control but high mortality. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013;471:510-8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engesæter LB, Dale H, Schrama JC, Hallan G, Lie SA. Surgical procedures in the treatment of 784 infected THAs reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2011;82:530-7. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lange J, Troelsen A, Thomsen RW, Søballe K. Chronic infections in hip arthroplasties: Comparing risk of reinfection following one-stage and two-stage revision: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Epidemiol 2012;4:57-73. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parvizi J, Tan TL, Goswami K, Higuera C, Valle CD, Chen AF, et al. The 2018 definition of periprosthetic Hip and Knee infection: An evidence-based and validated criteria. J Arthroplasty 2018;33:1309-14.e2. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lombardi AV Jr., Berend KR. The shattered femur: Radical solution options. J Arthroplasty 2006;21:107-11. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee YK, Lee KH, Nho JH, Ha YC, Koo KH. Retaining well-fixed cementless stem in the treatment of infected hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2013;84:260-4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekpo TE, Berend KR, Morris MJ, Adams JB, Lombardi AV Jr. Partial two-stage exchange for infected total hip arthroplasty: A preliminary report. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014;472:437-48. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosinsky PJ, Greenberg A, Amster-Kahn H, Campenfeldt P, Domb BG, Kosashvili Y. Selective component retainment in the treatment of chronic periprosthetic infection after total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2020;28:756-63. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leonard HA, Liddle AD, Burke O, Murray DW, Pandit H. Single-or two-stage revision for infected total hip arthroplasty? A systematic review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014;472:1036-42. [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Husseiny M, Haddad FS. The role of highly selective implant retention in the infected hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2016;474:2157-63. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ji B, Xu B, Guo W, Rehei A, Mu W, Yang D, et al. Retention of the well-fixed implant in the single-stage exchange for chronic infected total hip arthroplasty: An average of five years of follow-up. Int Orthop 2017;41:901-9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofmann AA, Kane KR, Tkach TK, Plaster RL, Camargo MP. Treatment of infected total knee arthroplasty using an articulating spacer. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1995;321:45-54. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scharfenberger A, Clark M, Lavoie G, O’Connor G, Masson E, Beaupre LA. Treatment of an infected total hip replacement with the PROSTALAC system. Part 1: Infection resolution. Can J Surg 2007;50:24-8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luk MH, Ng FY, Fu H, Chan PK, Yan CH, Chiu KY. Retention of prosthetic articulating spacer after infected hip arthroplasty as a semipermanent implant: A case report. J Orthop Trauma Rehabil 2019;26:105-7. [Google Scholar]