Pathological clavicular fracture from breast carcinoma can be a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge, but open reduction and internal fixation may be used effectively for symptomatic pain relief and return of function in the otherwise well patient.

Dr. Ben Murphy, Department of Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery, Cork University Hospital, Wilton, Cork, Ireland. E-mail: benmurphy@rcsi.com

Introduction: This is the first reported case of breast carcinoma metastasizing to the clavicle, causing a pathological fracture and subsequently being treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF).

Case Report: A 60-year-old female presented with shoulder pain after a minor trauma while swimming. She had prodromal pain and a breast cancer history. The radiograph revealed a right clavicle fracture. She had ongoing pain and no union on radiographs, with concern for a pathological fracture. Bone biopsy was performed and consistent with metastatic breast carcinoma involving the clavicle. ORIF was performed for symptomatic control. A 14-month follow-up revealed a healed fracture and a full return to activity.

Conclusion: A pathological clavicle fracture may be the presenting complaint of an unknown primary tumor or even signal recurrence of a previously treated malignancy. They can be challenging to diagnose and as such, we would urge surgeons to have a high index of suspicion in these cases. Excision of clavicular metastasis and partial or even full claviculectomy have been described in the literature. This is the first reported case of breast carcinoma metastasizing to the clavicle, causing a pathological fracture and subsequently being treated with ORIF. We would suggest that surgeons faced with this issue in the future consider it as a surgical option for pain relief and restoration of function in the otherwise fit and active patient.

Keywords: Pathological fracture, clavicle fracture, metastasis, clavicular metastasis.

Fractures of the clavicle are common and seen in both pediatric and adult populations [1]. Historically, the majority of these were treated conservatively, with a period of immobilization followed by early rehabilitation [2,3]. More recent literature would suggest that a certain cohort of patients may benefit from early union and improved function with immediate surgical treatment [4,5]. The non-operative management of skeletal metastatic disease has been well-described. However, there is a paucity in the literature regarding the management of pathologic clavicular fractures, particularly with regard to operative management. While it has been suggested that operative treatment of bony metastasis does not affect overall mortality, it can provide symptomatic relief to a vulnerable patient cohort [6]. Here, we share a case of a pathologic clavicle fracture, after minimal trauma, arising from a previously treated primary breast malignancy and our own experience with surgical management.

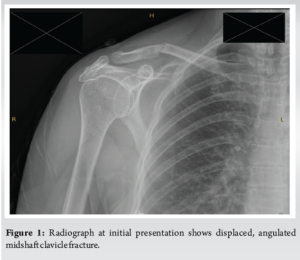

A 60-year-old female presented to the emergency department with pain and deformity of her right shoulder. The patient had been in open water swimming and raised her arms overhead to meet a wave when she felt a “crack” in her right shoulder area. The history revealed that she had prodromal pain in her shoulder region for several weeks before this incident. She had a background history of previous estrogen-receptor-positive breast carcinoma, for which she received full treatment for and recovered from. Her baseline was that of a very active and physically fit woman. Radiographs of the right shoulder were performed in the emergency department and revealed a right middle third clavicle fracture (Fig. 1). A trial of non-operative management followed, and the patient was given a shoulder immobilizer, discharged from the emergency department and given a follow-up appointment in our fracture clinic.

Unfortunately, the patient continued to have severe pain in her clavicular area and failed to progress with physiotherapy. Crucially, her radiographs showed little evidence of bony union. When comparing her follow-up radiographs with chest radiographs from 4 years previously, the appearance of her clavicle was notably different. A systems review confirmed that the patient had no recent weight loss, no change in bowel habits, or dysphagia. Cardiorespiratory and gastrointestinal system examinations were unremarkable, and no masses were palpable on digital rectal examination. Given the patient’s previous history of breast cancer and prodromal pain preceding her fracture, we became suspicious of a pathological fracture. Higher-order imaging was ordered in the form of a computed tomography of the thorax abdomen and pelvis, a bone scan, and an MRI of her right shoulder region. These revealed no other suspicious activity, only again around the fracture. A decision was made to proceed to a biopsy of the lesion so that further management could be facilitated.

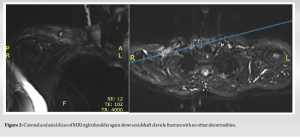

A bone biopsy was performed approximately 12 weeks after her initial presentation to the emergency department. Five biopsy samples were taken using a Jamshidi needle under a general anesthetic. Results revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma with nested and ductal morphology. Immunohistochemistry results (reported as per Guidelines of American Pathologists) demonstrated the following profile in the tumor cells: Estrogen Receptor: positive, Progesterone Receptor: positive, HER-2: negative. These results were all in keeping with a diagnosis of metastatic breast carcinoma involving the right clavicle. (Fig. 2).

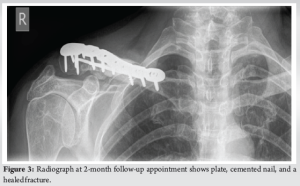

The patient’s oncologist was informed of the results and multidisciplinary discussions were had in light of this information. A discussion was had with the patient and their oncologist regarding the excision of the lesion (and a substantial portion of the clavicle) or whether to fix the fracture. As resection of the metastatic deposit would be unlikely to improve mortality, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) were favored for symptomatic control. One month after receiving her biopsy results, the patient underwent operative fixation of her pathological clavicle fracture. The clavicle segment containing the metastatic mass causing the fracture was excised medially and laterally leaving 1 cm of clear surgical margin. After excision, the defective area was reconstructed with a strut allograft and a cancellous allograft. The fixation was achieved using a locking plate. The patient progressed well following her operative intervention. Her pain levels and functional recovery were satisfactory at 2-week and 2-month follow-up appointments, respectively. She was delighted to have returned to sea swimming at the time of her 2-month appointment. On examination, her surgical wound was well-healed. She was also seen 14 months postoperatively. She had unfortunately fallen off her bicycle between appointments, injuring her right side. Despite this, her radiograph demonstrated a healed pathological fracture with appropriate positioning of metalwork. The patient was subsequently discharged from the fracture clinic at this point. (Fig. 3).

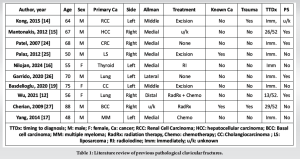

Metastasis to the bone is the most frequent site of metastasis after the liver and lung [7,8]. This is thought to be due to its rich vascular supply and abundant growth factors and chemoattractants produced by stromal cells, osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and other osteocytes [9]. Knudsen et al. declared three small branches of the subclavian artery including the suprascapular artery, the clavicular branch of the thoracoacromial artery, and the internal thoracic artery to be the primarily periosteal blood supply of the clavicle, with no nutrient artery [10]. This is thought to contribute to its relative sparing from metastatic lesions. Owing to its rarity, there is no clear consensus on its management in the literature, particularly with regard to operative management. Almost 60% of patients with upper limb metastatic disease present with pathologic fractures. Clavicular metastasis is rare, making up only 13.7% of upper limb bony metastasis. Malignancy of the clavicle, in general, is also rare, accounting for < 1% of all bone tumors [11]. One hypothesis to support this finding relates to sparse red marrow and minimal blood supply feeding the clavicle [12,13]. Consequently, skeletal metastasis normally occurs in large weight-bearing bones which have a higher metabolic demand [6,12]. The top three primary sources of clavicular metastasis are breast, prostate, and thyroid [7]. As with any bony metastasis, they may present with local signs and symptoms such as bone pain and fracture or with systemic signs such as hypercalcemia. In rare instances, pathological fractures of the clavicle may be the presenting complaint of an unknown primary malignancy elsewhere [14-17]. An extensive literature review was performed by the second author to identify previously described cases of clavicular fractures secondary to a malignant process. Pathological clavicle fractures secondary to infection/osteomyelitis, radiotherapy, or primary bone cancers were excluded. Search terms included “pathological clavicular fractures,” “metastasis, clavicular fracture,” and “breast metastasis, clavicle.” Of 539 papers, 10 were included after abstract screening by the first three authors, and consensus on inclusion was reached. A single paper reported breast metastasis to the clavicle. There was an expansile, destructive lesion present, but no fracture had occurred before surgical resection [18]. Therefore, to our knowledge, this is the first case report of metastatic breast carcinoma resulting in pathological clavicle fracture treated surgically. Our patient had a similar history of presenting complaints to previously reported clavicle fractures secondary to metastasis (Table 1). She had a relatively minor trauma and a history of prodromal pain, such as four of the 10 cases identified in the literature. As mentioned, we found no cases of pathological clavicle fracture secondary to primary breast carcinoma, highlighting the unique nature of our case. These are challenging diagnoses; indeed, three of the 10 published cases initially misdiagnosed the patient. We initially were not suspicious of pathological fracture until we closely examined the patient’s chest radiograph from a couple of years previously. This, coupled with her previous history and prodromal pain, aided the diagnosis. This is a good learning point for surgeons involved in the care of patients with pathological fractures, as a high index of suspicion must be maintained to ensure appropriate treatment. It also highlights the diagnostic challenges associated with rare presentations such as this, i.e., clavicular metastasis.

The surgical treatment of pathological clavicle fractures has been described [14,19,20]. However, these patients all underwent excision of the lesion plus partial claviculectomy. Ours is the first patient to have undergone ORIF for her pathological clavicle fracture. Adenocarcinoma is the predominant cell type in upper extremity metastatic lesions, as was the case with our patient. The role of surgical management of bony metastasis is still unclear [21,22]. Muramatsu et al. reported on the surgical treatment of 20 patients with upper extremity metastasis and the indications for the same [23]. Our decision to operatively manage this patient due to her pathological fracture and uncontrolled pain is mirrored in their work. Crucially, their series does not describe a single patient with surgically managed clavicular metastasis. This is where we feel the strength of our report lies and how other surgeons may learn from this patient’s journey.

While skeletal metastasis from primary tumors elsewhere is a common phenomenon, metastasis to the clavicle is rare, and fracture is even rarer. A pathological clavicle fracture may be the presenting complaint of an unknown primary tumor or even signal recurrence of a previously treated malignancy. They can be challenging to diagnose and as such, we would urge surgeons to have a high index of suspicion in these cases. Excision of clavicular metastasis and partial or even full claviculectomy have been described in the literature. This is the first reported case of breast carcinoma metastasizing to the clavicle, causing a pathological fracture and subsequently being treated with ORIF. We would suggest that surgeons faced with this issue in the future consider it as a surgical option for pain relief and restoration of function in the otherwise fit and active patient.

Pathological clavicular fracture from breast carcinoma can be a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge but ORIF may be used effectively for symptomatic pain relief and return of function in the otherwise well patient. This is the first reported case of breast carcinoma metastasizing to the breast, causing fracture, and subsequently being treated with ORIF. This case report highlights another treatment option which has therapeutic potential and may lead to satisfactory outcomes in other patients with this specific pathology.

References

- 1.Postacchini F, Gumina S, De Santis P, Albo F. Epidemiology of clavicle fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002;11:452-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Rowe CR. An atlas of anatomy and treatment of midclavicular fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1968;58:29-42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Andersen K, Jensen PO, Lauritzen J. Treatment of clavicular fractures. Figure-of-eight bandage versus a simple sling. Acta Orthop Scand 1987;58:71-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Sepehri A, Guy P, Roffey DM, O’Brien PJ, Broekhuyse HM, Lefaivre KA. Assessing the change in operative treatment rates for acute midshaft clavicle fractures: Incorporation of evidence-based surgery results in orthopaedic practice. JB JS Open Access 2023;8:e22.00096. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Ahrens PM, Garlick NI, Barber J, Tims EM, Clavicle Trial Collaborative Group. The clavicle trial: A multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing operative with nonoperative treatment of displaced midshaft clavicle fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017;99:1345-54. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Wisanuyotin T, Sirichativapee W, Sumnanoont C, Paholpak P, Laupattarakasem P, Sukhonthamarn K, et al. Prognostic and risk factors in patients with metastatic bone disease of an upper extremity. J Bone Oncol 2018;13:71-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Coleman RE. Metastatic bone disease: Clinical features, pathophysiology and treatment strategies. Cancer Treat Rev 2001;27:165-76. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Macedo F, Ladeira K, Pinho F, Saraiva N, Bonito N, Pinto L, et al. Bone metastases: An overview. Oncol Rev 2017;11:321. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Ban J, Fock V, Aryee DN, Kovar H. Mechanisms, diagnosis and treatment of bone metastases. Cells 2021;10:2944. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Knudson JD, Lopez KN, Maskatia S, McKenzie ED, Lantin-Hermoso MR, Masand PM, et al. Type B interrupted left aortic arch with isolated right subclavian artery. Congenit Heart Dis 2012;7:E25-30. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Ren K, Wu S, Shi X, Zhao J, Liu X. Primary clavicle tumors and tumorous lesions: A review of 206 cases in East Asia. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2012;132:883-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Wu K, Huang YH. A rare case report: An inextricable shoulder pain as the exclusive presentation of lung adenocarcinoma with metastasis over contralateral clavicle. Eur J Med Res 2021;26:23. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Priemel MH, Stiel N, Zustin J, Luebke AM, Schlickewei C, Spiro AS. Bone tumours of the clavicle: Histopathological, anatomical and epidemiological analysis of 113 cases. J Bone Oncol 2019;16:100229. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Kong Y, Wang J, Li H, Guo P, Xu JF, Feng HL. Pathological clavicular fracture as first presentation of renal cell carcinoma: A case report and literature review. Cancer Biol Med 2015;12:409-12. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Mantonakis EI, Margariti TS, Petrou AS, Stofas AC, Lazaris AC, Papalampros AE, et al. A pathological fracture and a solitary mass in the right clavicle: An unusual first presentation of HCC and the role of immunohistochemistry. World J Surg Oncol 2012;10:50. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Nilojan JS, Raviraj S, Madhuwantha UV, Mathuvanthi T, Priyatharsan K. Metastatic thyroid follicular carcinoma presenting as pathological left clavicle fracture: An unusual skeletal metastasis at the time of diagnosis. Int J Surg Case Rep 2024;114:109131. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Yang SM, Lo CM. A man with a fracture from minor trauma. World J Emerg Med 2014;5:306-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Glover TE, Butel R, Bhuller CM, Senior EL. An unusual presentation of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast with metastatic disease in the clavicle. BJR Case Rep 2017;3:20160119. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Başdelioğlu K. Pathological clavicle fracture: Initial presentation of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Cureus 2020;12:e7094. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Coca Pelaz A, Núñez Batalla F, Vivanco Allende B, Díaz Molina JP, Suárez Nieto C. Giant neck liposarcoma with pathological clavicular fracture. Auris Nasus Larynx 2010;37:394-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Harrington KD. Orthopedic surgical management of skeletal complications of malignancy. Cancer 1997;80(8 Suppl):1614-27. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Healey JH, Brown HK. Complications of bone metastases: Surgical management. Cancer 2000;88(12 Suppl):2940-51. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 23.Muramatsu K, Ihara K, Iwanagaa R, Taguchi T. Treatment of metastatic bone lesions in the upper extremity: Indications for surgery. Orthopedics 2010;33:807. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 24.Patel NN, Shah PR, Wilson E, Haray PN. An unexpected supraclavicular swelling. World J Surg Oncol 2007;5:90. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 25.Pelaz AC, Batalla FN, Allende BV, Diaz Molina JP, Nieto CS. Giant neck liposarcoma with pathological clavicular fracture. Auris Nasus Larynx 2010;37:394-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 26.Garrido DG, Cañizares AP, Bisaccia M, Meccariello L, Delgado EF. Pathological clavicle fracture as the first symptom of lung cancer. J Orthop Case Rep 2020;10:54-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 27.Cherian P, Kumarasinghe P. Giant basal cell carcinoma masquerading as an osteogenic sarcoma. Australas J Dermatol 2009;50:60-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]