Internal fixation may cause bone atrophy and necrosis, even when using modern plate de-signs.

Dr. Hanna Wellauer, Division of Orthopaedics and Trauma-tology, Cantonal Hospital, Brauerstrasse 15/PO box 834, 8401, Winterthur, Switzerland. E-mail: hanna.wellauer@ksw.ch

Introduction: Periprosthetic fractures (PPF) of the proximal femur are a leading cause of revision after total hip arthroplasty. Internal fixation may be chosen if the hip implant is stable or if a stable fixation may be obtained. Preservation of bone perfusion and adequate stability are essential for successful fracture healing. As presented, plate design and applica-tion may induce both osteonecrosis and atrophy of the bone.

Case Report: An 82-year-old female sustained a PPF of the proximal femur after cemented hemiarthroplasty. The fracture was treated by plate fixation with cerclages applied at the level of the femoral stem. While the fracture healed without loosening of the components, pronounced atrophy of the whole femur developed, with devitalized areas of the bone un-derlying the plate. The plate used had no undercuts and probably had excessive stiffness.

Conclusion: When not strictly applied as an internal fixator at a distance from the bone, the plate model used in this case may disturb periosteal blood flow, causing osteonecrosis. Fur-thermore, high bending rigidity of the plate-bone construct may lead to stress shielding and atrophy. Design and mechanical properties of a plate are relevant in fracture healing.

Keywords: Periprosthetic fracture, plate fixation, internal fixation, bone biology, bone ne-crosis, plate contact.

Periprosthetic fractures (PPF) of the proximal femur are one of the most frequent causes of revision after total hip arthroplasty as well as after hip hemiarthroplasty (HHA) [1,2,3]. Revision of the stem is not always necessary in case of PPF, even if the fracture affects the area of anchorage of the implant. Internal fixation with cerclages and plate may be an adequate treatment option if the prosthetic stem is stable, or if a stable construct may be obtained with fixation [2,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Preservation of bone perfusion and adequate stability are essential for bone healing and thus the success of internal fixation [11]. One of the main issues with internal fixation using plates is the potential compromise of bone perfusion by compression of the periosteal blood flow due to contact of the implant [12,13,14,15]. Despite increasing experience and further development of internal fixation techniques for many decades, classical problems associated with plate fixation may still happen nowadays. The observations reported provide exceptional insights into both the issues of necrosis and atrophy of the cortical bone following plate fixation of a PPF of the femur. Identification of these complications led to further investigations of the mechanical properties of plates commonly used in this indication. The design and mechanical characteristics of the plate used probably contributed to both complications. Even if limited to a single case, this report may provide important insights to improve internal fixation, beyond the issues of PPF of the proximal femur.

An 80-year-old female had been treated with a cemented HHA (AMIStem-C, Medacta, Castel San Pietro, Switzerland) for a low-energy femoral neck fracture (Fig. 1a). Two years later, the now 82-year-old patient tripped and fell again, suffering a PPF of the femur (Figs. 1b and 2).

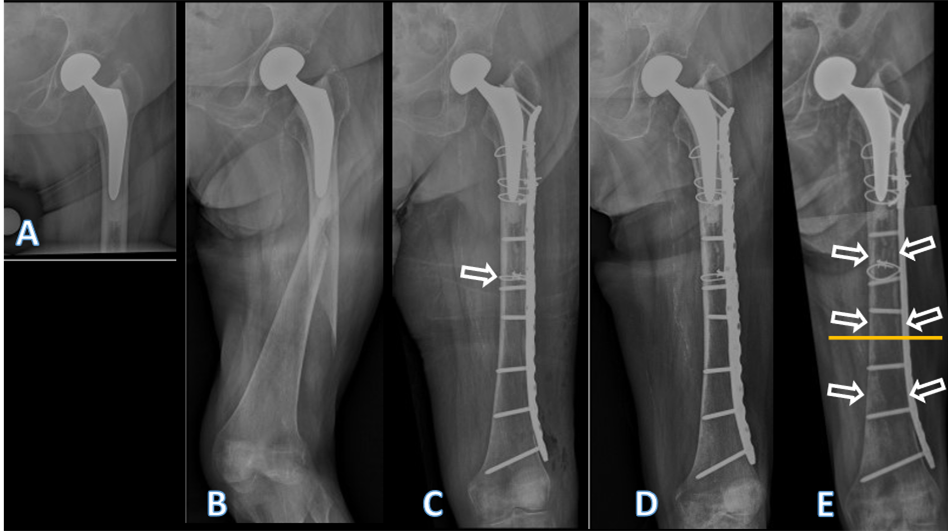

Figure 1: Conventional anteroposterior radiographs of the left hip, respectively, the left fe-mur of the patient described. In (a) after cemented hemiarthroplasty, performed due to a femoral neck fracture, at an age of 80 years. In (b) periprosthetic spiral fracture of the fem-oral diaphysis, 2 years postoperatively, following a low-energy fall. In (c) after internal fix-ation of the femur. The fracture was first reduced with a cerclage (arrow), then a lateral neu-tralization plate was applied, fixated proximally with further cerclages and distally with screws. In (d) follow-up 4 months after internal fixation. Note that no callus formation is visible, indicative of absolute stability. In (e) follow-up 4 years after internal fixation. Note the atrophy of the cortical bone, both medially and laterally, but particularly under the plate (arrows). There were no signs of loosening of the stem, nor of the cement mantle. The yel-low line marks the level of the cross-section from Figs. 4 and 5.

Figure 2: Coronal (a) and sagittal (b) computed tomography (CT) scan reconstructions of the left femur of the patient described, showing the periprosthetic fracture. The extension of the fracture into the lateral cortex at the level of the tip of the stem arrow in (a) as well as a fracture of the cement distally to the tip of the stem arrow in (b) are visible. Both fracture extensions had been missed by the treating team. Accordingly, and considering the line-to-line principle of cementation of the affected stem, the fracture should be classified at least as Unified Classification System Type B2, if not B3, and not as a type C. The sublux-ated appearance of the head of the femoral head prosthesis is an artifact due to movement of the patient during the CT examination.

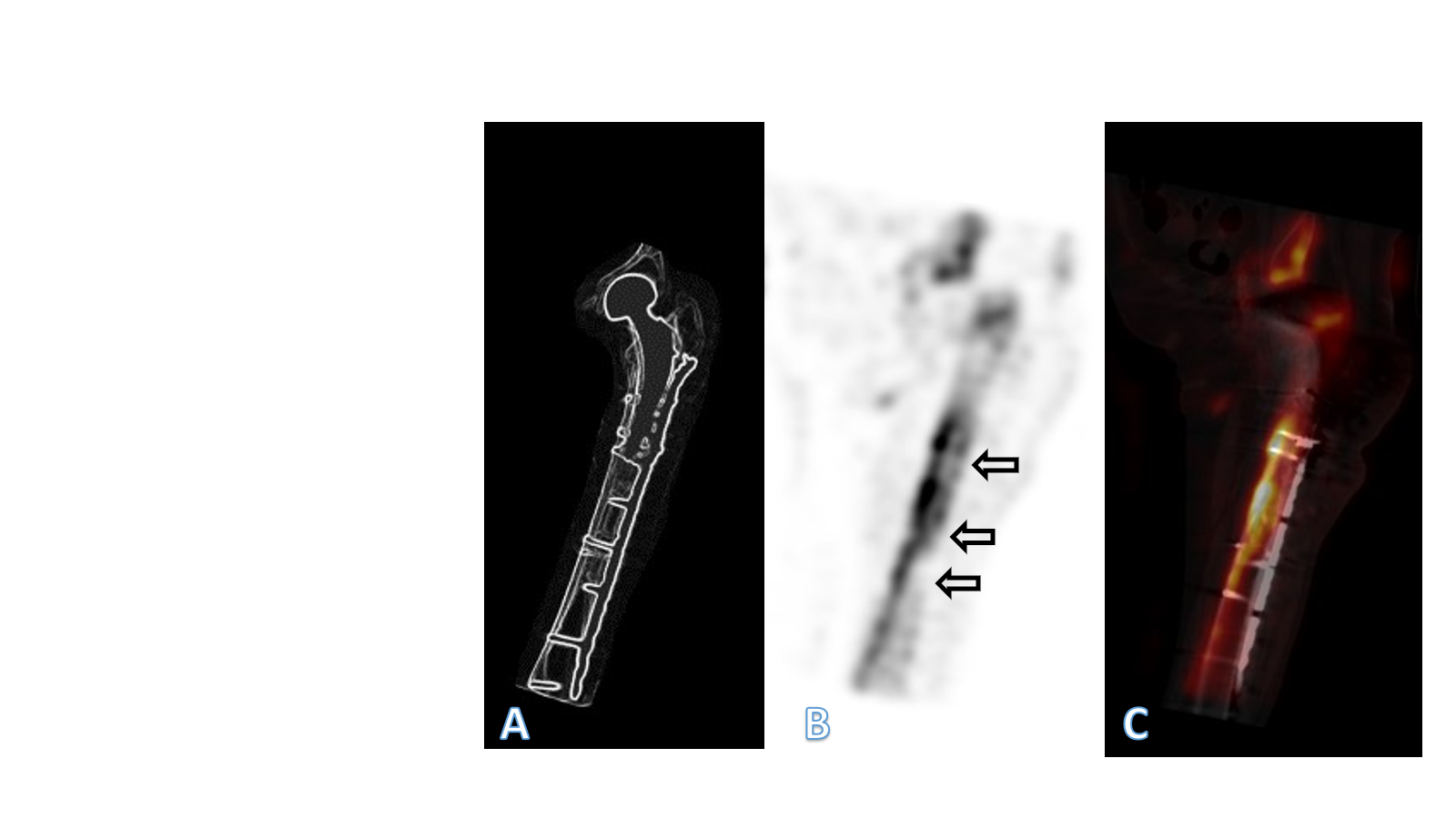

As the treating team considered the stem to be stable, with a fracture evaluated as being located distally to the area of fixation (Unified Classification System [UCS] Type C) [17], plate fixation was chosen. Open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture was performed through a subvastus approach, with reduction and fixation by a cable cerclage (Cable System 1.7 mm, DePuy Synthes, Zuchwil, Switzerland) and application of a lateral neutralization plate (non-contact bridging [NCB] Periprosthetic Femur Plate System 18 hole, Zimmer Biomet, Zug, Switzerland), fixated distally with screws and along the level of the stem with further cable cerclages (Cable System 1.7 mm). Postoperatively, the patient was mobilized in a wheelchair, as full weight-bearing was not recommended and as it was not possible to implement partial weight-bearing. Wound healing was uneventful. The radiological follow-up after 8 weeks showed intact material without evidence of loosening (Fig. 1c). Mobilization under full weight-bearing with support by physical therapy was then attempted. Four months postoperatively, the radiological follow-up showed a general atrophy of the cortical bone, which was accentuated at the lateral cortex, underneath the plate (Fig. 1d). Mobilization was hampered due to thigh pain, which had been interpreted to be caused by muscle atrophy. Thus, further physical therapy was recommended. As the impaired mobility caused difficulties attending consultation at the hospital, no further follow-up visits were planned. Due to increasing thigh pain, the patient was readdressed for evaluation by her general practitioner 4 years after the operative treatment of the PPF. Not having been mobilized outside a wheelchair in the meantime, the patient showed bilateral hip and knee flexion contractures. Consequently, she was unable to stand, disregarding the issue of thigh pain. Radiologically, there was now pronounced atrophy of the cortical bone of the femur, particularly of the lateral cortex under the plate (Fig. 1e). An infection was considered unlikely, as there was no pain at rest, as the soft tissues were inconspicuous, as the fracture had healed, and as there were no general symptoms. A single-photon emission computed tomography (CT) showed avascular areas of cortical bone underneath the plate (Fig. 3). The CT better illustrated a general atrophy of the femur with thinning of the bone cortex in comparison to the contralateral femur (Fig. 4 and 5). There was, however, no sign of loosening of the stem. Considering comorbidities, very limited potential for recovery, and the patients’ desire for no more surgery, the option of a revision was rejected, accepting the present situation. The patient died 7 months later.

Figure 3: In (a) overview image for orientation. In (b) paracoronal view of the single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) of the left femur 4 years after plate fixation of a periprosthetic fracture of the proximal femur after cemented hemiarthroplasty of the hip. In (c) paracoronal reconstruction of the SPECT/computed tomography fusion image of the left femur, also illustrating the implant. The bone directly under the plate showed no detectable metabolic activity in various areas, a typical image of bone necrosis (arrows). In the area of the medial cortex, however, there was compensatory increased activity, which is to be ex-plained by the atrophy of the bone.

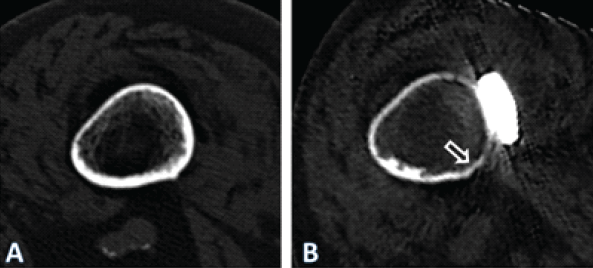

Figure 4: Axial computed tomography (CT)-scan images illustrating the cross-section of the femoral diaphysis of the patient described, at the level of the yellow line in Fig. 1. In (a) at the time of the periprosthetic fracture. In (b) 4 years after internal fixation with a lateral plate. Note general atrophy with thinning out of the cortex. In the area under the plate (ar-row), there were areas of necrosis, with no detectable bone metabolism in a single-photon emission CT. The quality of the image in (b) is reduced due to artifacts caused by the im-plants and due to the movement of the patient during the procedure. Only the geometry of the bone may be compared. The apparent density of the bone is affected by differing acqui-sition protocols as well as due to artifacts induced by the implants, limiting comparison of the density

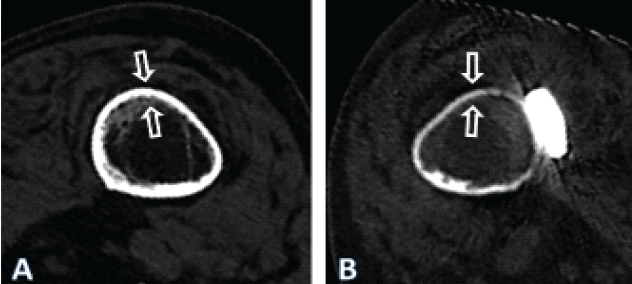

Figure 5: Computed tomography scan images 4 years after fixation of the periprosthetic fracture of the left femur after cemented hemiarthroplasty of the hip in the patient described, illustrating the cross-section at the level of the yellow line in Fig. 1, for both the right (a) and the left (b) femur. Note the general atrophy of the bone of the left femur, compared to the thickness of the cortex of the right femur, which may be considered normal at such age in females, despite immobilization. There nevertheless is a cancellous transformation at the inner cortex of the right femur, typical for endosteal resorption, as expected after prolonged unloading, the patient having never regained walking ability.

Mechanical properties of the plates

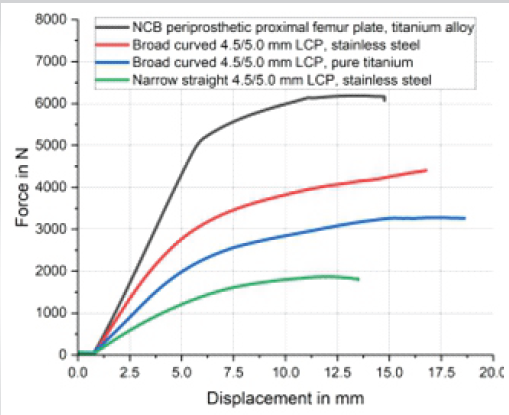

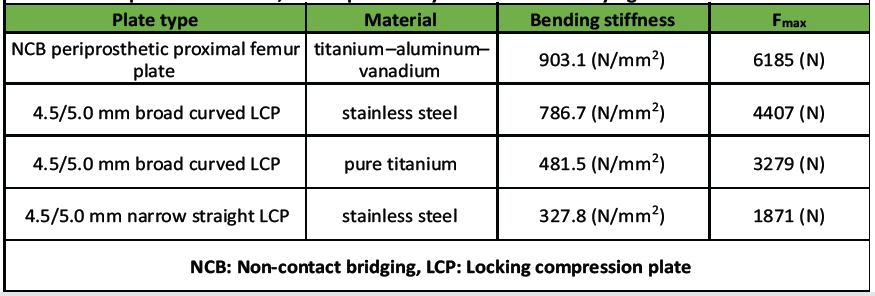

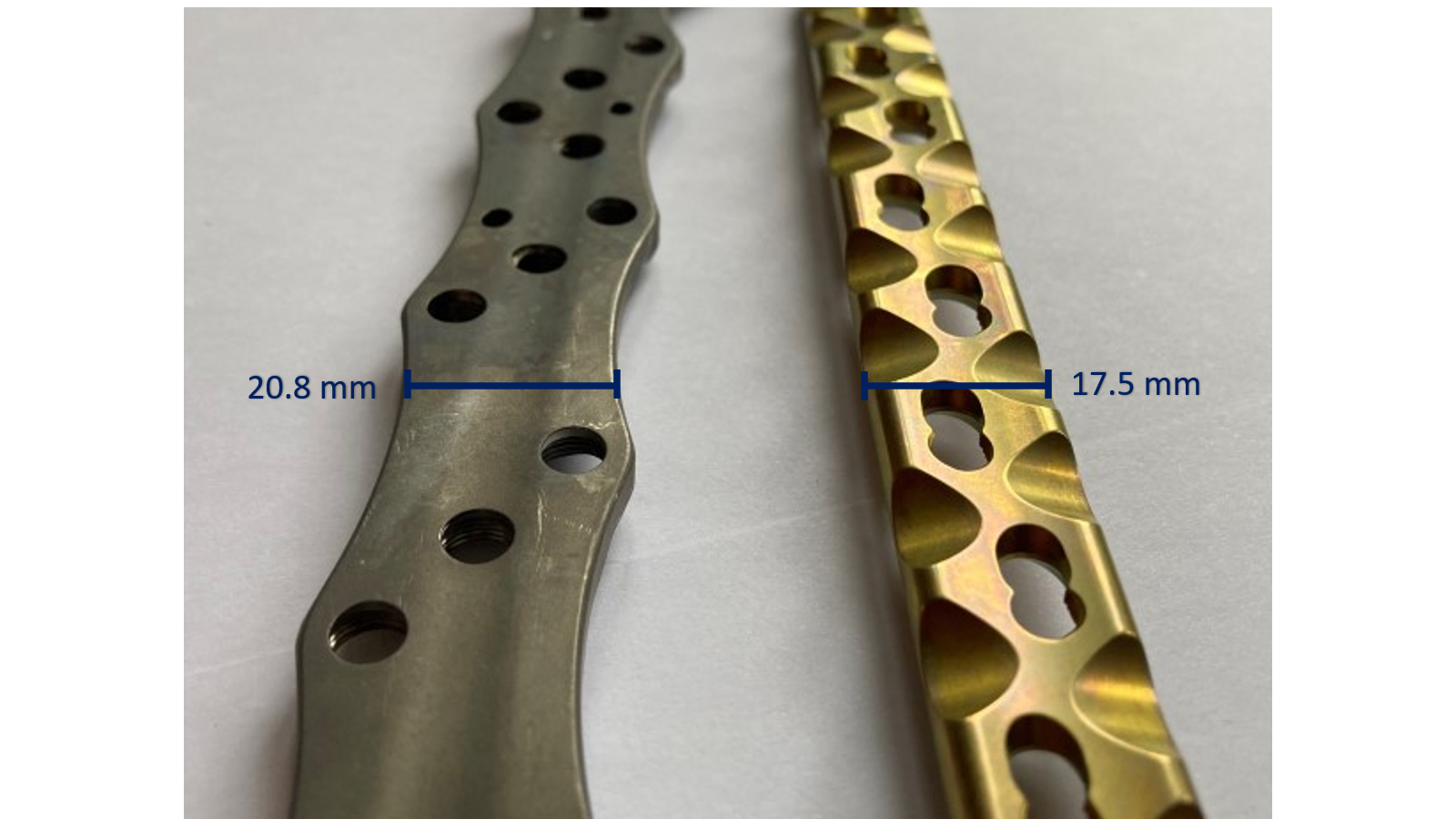

The following plates were chosen for further investigation: a NCB plate, made of titanium–aluminum–vanadium alloy, corresponding to the one used in this case, a broad curved 4.5/5.0 mm locking compression plate (LCP) made of stainless steel (DePuy Synthes, Oberdorf, Switzerland), a broad curved 4.5/5.0 mm LCP made of forged titanium (DePuy Synthes) and a narrow 4.5/5.0 mm LCP made of stainless steel (DePuy Synthes). Differing from the LCP design, the NCB plate has a varying cross-section along the length of the plate. The plates were photo-documented and dimensions measured before destructive testing. A 4-point bending test according to American Society for Testing and Materials F382-17 was performed to determine the bending behavior of the plates [18]. The NCB plate, considering the non-uniform cross-section in the longitudinal axis, was positioned according to the in vivo situation, the compression area corresponding approximately to the tip of the stem (Fig. 1). The undersurface of the NCB has a design markedly different from the LCP, as it has a longitudinal groove adapting to the curvature of the femoral diaphysis and it has no undercuts (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Results of the 4-point bending test according to ASTM F382-17 of the four plates tested. The non-contact bridging plate was tested at the approximate level of the tip of the stem of the total hip replacement in the patient described, as this plate is asymmetric with a varying cross-section. As a comparison, a narrow 4.5/5.0 mm locking compression plate (LCP) made of stainless steel, a broad curved 4.5/5.0 mm LCP made of stainless steel, and a broad curved 4.5/5.0 mm LCP made of pure titanium were tested.

While having nearly the same thickness (NCB: 6.2 mm, 4.5/5.0 mm LCP: 5.8 mm), the NCB is wider (20.8 mm at the approximate level of the tip of the stem in this case) than the broad 4.5/5.0 mm LCP plate (17.5 mm; Fig. 6). Considering the cross-section being rectangular and disregarding screw holes, the cross-sectional area of the NCB at the level of interest is 129 mm2, and 101.5 mm2 for the broad 4.5/5.0 mm LCP, thus 27% larger for the NCB. The axial area moment of inertia of the plate (Iz=1/12 × [height3 × width]), representing the resistance of the cross-section against bending, would be approximately 413 mm4 for the NCB plate and thus approximately 45% greater than for the broad 4.5/5.0 mm LCP, which has approximately 285 mm4. Considering the modulus of elasticity of pure and alloyed titanium is equal, the bending stiffness of the NBC would be 45% greater than that of the broad LCP. There were marked differences between the four plates regarding bending behavior (Table 1 and Fig. 6).

Table 1: Results of the 4-point bending test according to ASTM F382-17 of the 4 plates tested. The NCB plate was tested at the approximate level of the tip of the stem of the total hip replacement in the patient described, as this plate is asymmet-ric with a varying cross-section

The narrow 4.5/5.0 mm LCP had the lowest resistance to bending. The titanium alloy NCB plate had the highest stiffness and resistance to bending due to its greater cross-section. The NCB was about twice as rigid as the broad LCP made of pure titanium. The broad 4.5/5.0 mm LCP made of stainless steel was about twice as rigid as the narrow 4.5/5.0 mm LCP of the same material.

The treatment of a PPF with internal fixation is an established surgical treatment option [8,19]. Whether internal fixation is adequate for treatment of PPF of the femur depends on the stability of the stem, respectively, the fracture pattern and localization, as well as potential stability after fixation [2]. The general condition of the patient may also be part of the decision-making process, internal fixation being potentially less invasive than stem revision. Thus, internal fixation may be an acceptable option in case of severe comorbidities and limited functional requirements, even if otherwise, stem revision would be the treatment of choice from a mechanical point of view [9,19,20,21,22,23,24]. In the presented case, the fracture had been classified by the treating team as a type C fracture, according to the UCS classification [17]. However, a more detailed analysis of the CT scan showed an extension of the fracture into the lateral cortex at the level of the tip of the stem, as well as a fracture of the cement at the same level (Fig. 2). Cement fixation of the stem design used in this case was based on the line-to-line concept [25,26,27]. An interruption of the connection between the stem and the cement leads to an unstable situation with this kind of cementation principle [2,27]. Therefore, the fracture should have been classified correctly as a type B2, possibly even B3, considering the poor bone quality. Low functional demands were probably decisive regarding the outcome of the stem, as the patient never became ambulatory again. Thorough radiologic work-up of PPF, including evaluation of the zone of fixation of the affected implant, is recommended before decision-making [20]. When opting for internal fixation, it is recommended to apply a plate spanning the entire length of the femur [8]. Various implants are available for the treatment of PPF. Universal plates, such as the standard large fragment LCP (DePuy Synthes), which is also available curved, can be used. Alternatively, anatomically pre-shaped plates are available from different manufacturers, such as the NCB plate (Zimmer Biomet), which was applied in this case. The latter plate possesses some specific design features that need consideration when employing it for internal fixation of PPF. A relevant proportion of the blood supply to the bone of the diaphysis originates from the periosteum [12,28]. Implants used for internal fixation, such as conventional plate-screw-constructs, can impede blood supply by exerting direct pressure on the bone, consecutively increasing the risk of local bone necrosis and non-union [11,12,13,15,29]. Undercuts have been incorporated into plate designs to reduce contact with the underlying bone and preserve blood supply [11,12,13,15,29,30]. In contrast, the undersurface of the NCB plate lacks such indentations (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Undersurface of the non-contact bridging (NCB) periprosthetic proximal femur plate (Zimmer Biomet, Zug, Switzerland) on the left and of a broad curved 4.5/5.0 mm locking compression plate (LCP) (DePuy Synthes, Oberdorf, Switzerland) on the right. Note that the NCB has no undercuts and has a longitudinal groove, increasing contact with the tubular diaphyseal bone, whereas the LCP has several undercuts to reduce contact of the plate with the underlying bone.

When applied directly to the bone, the longitudinal groove of the NCB may potentially compromise blood perfusion on a relatively large surface, especially if the edges of the groove compress the periosteum. In the present case, the plate had been applied in direct contact with the bone and with considerable pressure, exerted by the cerclages and conventional, non-locking screws. Cortical bone necrosis due to compression of the periosteal vessels may be avoided if the NCB plate is used as an internal fixator, applied at a distance from the bone. However, this may not be possible if cerclages have to be used to avoid interference of screws with the prosthesis stem and/or cement. While the NCB system offers the possibility to use stub screws as distance holders, this may prove inadequate in such situations. Cerclages are usually necessary in the segment of the underlying stem to achieve and maintain adequate reduction of the bone fragments and stabilize the plate. In case of osteoporosis, stub screws would be prone to being crushed into the bone, failing the distance holding function, or creating additional fracture lines. In addition, cortical screws are often required in the distal plate segment for reduction or to reduce the risk of later peri-implant fracture [31]. This would lead to loss of the non-contact concept of the NCB plate and compression of the periosteum by the plate. Besides the biological advantages of plate undercuts, they also serve to homogenize stiffness along the plate despite the presence of screw holes [32]. This is obtained on the NCB plate with various outcuts, which, however, do not offer any protection for the periosteal blood vessels. Surgeons should be aware of the technical features and specificities of the implants, as plate design may vary greatly. In the presented case, the fracture healed despite the application of the plate, and there was no mechanical failure of the plate itself. However, marked atrophy of the cortical bone developed (Figs. 1, 3, 4, and 5), in addition to the necrosis of the bone directly under the plate (Fig. 4). The stiffness of the plate-bone composite beam leads to unloading of the underlying bone (stress shielding). Mechanical unloading of the bone cortex is probably triggering bone remodeling and localized bone atrophy as a long-term effect [33]. Avoidance of post-operative weight-bearing certainly was contributive, but as the contralateral femur did not develop any particular atrophy, rigidity of the fixation may be considered the main cause in this case. The hip replacement implant may not be incriminated, as the atrophy appeared far more distally along the femur. Even if the bending stiffness of the various plates differs only moderately, the bending rigidity of the plate-bone composite beam may, however, be increased by a much higher proportion and end up being excessive and problematic [34]. The mechanical properties of the plate have to be incorporated by the surgeon in his appreciation of the adequacy of fixation. This, however, remains very subjective. No more precise recommendations regarding the rigidity of internal fixation constructs are available. Beyond fracture classification and localization, implant specificities should also be considered when performing internal fixation. Both the material properties and the design of the plate, particularly the cross-sectional area, are essential determinants of the bending stiffness and behavior of the implant [34]. The NCB plate is made of titanium–aluminum–vanadium alloy, which shares a similar elasticity modulus with the pure titanium used for AO/ASIF-standard implants [35,36]. Among the metals and alloys employed for orthopedic implants, pure and alloyed titanium come closest to the elasticity of bone, albeit their modulus of elasticity remains up to 7-fold higher than that of cortical bone, whose modulus of elasticity is generally between 17 and 28 GPa [37,38,39]. In the static bending test carried out, the NCB plate demonstrated the highest bending stiffness among the four implants tested. Calculation of cross-sectional properties and measurement of the bending behavior of the plate both confirm the highest stiffness for the NCB plate among the implants selected. The broad 4.5/5.0 mm LCP made of pure titanium has a significantly lower stiffness than the NCB plate, despite being made of metals with a similar elasticity modulus. Even though the modulus of elasticity of stainless steel (approximately 190–200 GPa) is higher than for pure and alloyed titanium (approximately 110 GPa), the test shows that the NCB plate is stiffer than a broad 4.5/5.0 mm LCP made of stainless steel. This difference can be attributed to the much larger cross-section of the NCB plate (Fig. 7). It is worth noting that plates and constructs with higher rigidity have been identified as a risk factor for non-union of distal femur fractures, suggesting that excessive rigidity may be detrimental in fracture fixation [40]. Regaining walking ability following a PPF of the femur is challenging, with only half of the patients able to return to their initial functional level Elderly people are usually not able to maintain partial weight-bearing [42,43]. Therefore, post-operative mobilization of the patients commonly is limited to a wheelchair, for fear that full weight-bearing may overload the recently performed fracture fixation. However, such immobilization can have dire consequences for these predominantly elderly and frail patients, as demonstrated in the case presented. Immobilization leads to loss of bone and muscle mass, and it accelerates mental deterioration [44,45,46]. Consequently, the treatment of PPF of the femur should aim at early mobilization of the patient to ensure a functionally good result. Internal fixation of PPF of the femur in the elderly should ideally provide enough stability to allow unrestricted weight-bearing and early mobilization. In case of a simple PPF and low-energy traumatism, optimal stability is achieved best with a tension-band plating (load-sharing concept). Unfortunately, this possibility is often overlooked, particularly with the rising popularity of new anatomically pre-shaped plating systems designed as internal fixators. Nevertheless, even internal fixators can be utilized as effective tension band stabilization systems when applied appropriately. The good old principles of internal fracture fixation should, however, not be forgotten and applied strictly, even or particularly when using modern, pre-shaped, anatomic implants.

When not strictly applied as an internal fixator at a distance from the bone, the NCB plate, which had been used in this case, may disturb periosteal blood flow, causing osteonecrosis, as it has no undercuts. Furthermore, high bending rigidity of the plate-bone construct may lead to stress shielding and atrophy of the bone. Design and mechanical properties of a plate are relevant in fracture healing and should be considered when performing internal fixation.

• The application of a plate without undercuts in direct contact with the bone impairs periosteal blood flow, possibly leading to bone necrosis.

• The rigidity of the plate-bone construct in internal fixation may be excessive and lead to bone atrophy due to stress shielding; as there are no clear cutoff values and as evaluation of rigidity remains subjective, internal fixation remains an art.

• Modern, anatomic plates, developed to solve certain issues observed previously, may also lead to new problems in internal fixation.

References

- 1. Abdel M, Watts C, Houdek M, Lewallen D, Berry D. Epidemiology of periprosthetic fracture of the femur in 32 644 primary total hip arthroplasties: A 40-year experience. Bone Joint J 2016;98:461-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Stoffel K, Horn T, Zagra L, Mueller M, Perka C, Eckardt H. Periprosthetic fractures of the proximal femur: Beyond the Vancouver classification. EFORT Open Rev 2020;5:449-56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. SIRIS. Swiss National Hip and Knee Joint Registry Annual Report 2023; 2023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Moloney GB, Westrick ER, Siska PA, Tarkin IS. Treatment of periprosthetic femur fractures around a well-fixed hip arthroplasty implant: Span the whole bone. Arch Othop Trauma Surg 2014;134:9-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Xue H, Tu Y, Cai M, Yang A. Locking compression plate and cerclage band for type B1 periprosthetic femoral fractures preliminary results at average 30-month fol-low-up. J Arthroplasty 2011;26:467-71.e1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Buttaro M, Farfalli G, Núñez MP, Comba F, Piccaluga F. Locking compression plate fixation of Vancouver type-B1 periprosthetic femoral fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89:1964-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Ehlinger M, Adam P, Moser T, Delpin D, Bonnomet F. Type C periprosthetic frac-tures treated with locking plate fixation with a mean follow up of 2.5 years. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2010;96:44-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Froberg L, Troelsen A, Brix M. Periprosthetic Vancouver type B1 and C fractures treated by locking-plate osteosynthesis: Fracture union and reoperations in 60 con-secutive fractures. Acta Orthop 2012;83:648-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. González-Martín D, Pais-Brito JL, González-Casamayor S, Guerra-Ferraz A, Ojeda-Jiménez J, Herrera-Pérez M. Treatment algorithm in Vancouver B2 peripros-thetic hip fractures: Osteosynthesis vs revision arthroplasty. EFORT Open Rev 2022;7:533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Graham SM, Moazen M, Leonidou A, Tsiridis E. Locking plate fixation for Vancou-ver B1 periprosthetic femoral fractures: A critical analysis of 135 cases. J Orthop Sci 2013;18:426-36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Perren SM. Evolution of the internal fixation of long bone fractures. The scientific basis of biological internal fixation: Choosing a new balance between stability and biology. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002;84:1093-110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Jacobs RR, Rahn BA, Perren SM. Effects of plates on cortical bone perfusion. J Trauma 1981;21:91-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Field JR, Hearn TC, Caldwell CB. Bone plate fixation: An evaluation of interface contact area and force of the dynamic compression plate (DCP) and the limited con-tact-dynamic compression plate (LC-DCP) applied to cadaveric bone. J Orthop Trauma 1997;11:368-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Gautier E, Rahn B, Perren S. Vascular remodelling. Injury 1995;26:B11-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Perren SM, Cordey J, Rahn BA, Gautier E, Schneider E. Early temporary porosis of bone induced by internal fixation implants. A reaction to necrosis, not to stress pro-tection? Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988;232:139-51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Bottlang M, Doornink J, Lujan TJ, Fitzpatrick DC, Marsh JL, Augat P, et al. Effects of construct stiffness on healing of fractures stabilized with locking plates. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92:12-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Duncan CP, Haddad FS. The unified classification system (UCS): Improving our un-derstanding of periprosthetic fractures. Bone Joint J 2014;96:713-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. ASTM. ASTM Volume 13.01: Medical and Surgical Materials and Devices (I): E667-F2477. United States: ASTM; 2023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Gonzalez-Martin D, Hernández-Castillejo LE, Herrera-Pérez M, Pais-Brito JL, Gon-Zalez-Casamayor S, Garrido-Miguel M. Osteosynthesis versus revision arthroplasty in Vancouver B2 periprosthetic hip fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2022;49:87-106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Patsiogiannis N, Kanakaris NK, Giannoudis PV. Periprosthetic hip fractures: An up-date into their management and clinical outcomes. EFORT Open Rev 2021;6:75-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Mondanelli N, Troiano E, Facchini A, Ghezzi R, Di Meglio M, Nuvoli N, et al. Treatment algorithm of periprosthetic femoral fracturens. Geriatr Orthop Surg Re-habil 2022;13:21514593221097608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Niikura T, Lee SY, Sakai Y, Nishida K, Kuroda R, Kurosaka M. Treatment results of a periprosthetic femoral fracture case series: Treatment method for Vancouver type b2 fractures can be customized. Clin Orthop Surg 2014;6:138-45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Spina M, Scalvi A. Vancouver B2 periprosthetic femoral fractures: A comparative study of stem revision versus internal fixation with plate. Eur J Orthop Surg Trau-matol 2018;28:1133-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Stoffel K, Blauth M, Joeris A, Blumenthal A, Rometsch E. Fracture fixation versus revision arthroplasty in Vancouver type B2 and B3 periprosthetic femoral fractures: A systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2020;140:1381-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Verdonschot N. Philosophies of stem designs in cemented total hip replacement. Or-thopedics 2005;28:S833-40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Scheerlinck T, Casteleyn PP. The design features of cemented femoral hip implants. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2006;88:1409-18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Beel W, Klaeser B, Kalberer F, Meier C, Wahl P. The effect of a distal centralizer on cemented femoral stems in arthroplasty shown on radiographs and SPECT/CT: A case report. JBJS Case Connect 2021;11:e20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Rhinelander FW. The normal microcirculation of diaphyseal cortex and its response to fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1968;50:784-800. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Gautier E, Perren SM. Limited contact dynamic compression plate (LC-DCP)–biomechanical research as basis to new plate design. Orthopade 1992;21:11-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Gautier E, Sommer C. Guidelines for the clinical application of the LCP. Injury 2003;34:B63-76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 31. Bottlang M, Doornink J, Byrd GD, Fitzpatrick DC, Madey SM. A nonlocking end screw can decrease fracture risk caused by locked plating in the osteoporotic diaphy-sis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:620-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 32. Perren S, Mane K, Pohler O, Predieri M, Steinemann S, Gautier E. The limited con-tact dynamic compression plate (LC-DCP). Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1990;109:304-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 33. Gautier E, Perren SM, Cordey J. Strain distribution in plated and unplated sheep tibia an in vivo experiment. Injury 2000;31:C37-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 34. Gautier E, Perren S, Cordey J. Effect of plate position relative to bending direction on the rigidity of a plate osteosynthesis. A theoretical analysis. Injury 2000;31:C14-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 35. Disegi J. Implant Materials. IN: Titanium – 6% Aluminum – 7% Niobium. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 36. Zimmer. Periprosthetic Bone Plate. United States: Zimmer; 2011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 37. Niinomi M. Mechanical properties of biomedical titanium alloys. Mater Sci Eng 1998;243:231-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 38. Geetha M, Singh AK, Asokamani R, Gogia AK. Ti based biomaterials the ultimate choice for orthopaedic implants-a review. Prog Mater Sci 2009;54:397-425. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 39. Dickenson RP, Hutton WC, Stott JR. The mechanical properties of bone in osteopo-rosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1981;63:233-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 40. Rodriguez EK, Zurakowski D, Herder L, Hall A, Walley KC, Weaver MJ, et al. Me-chanical construct characteristics predisposing to non-union after locked lateral plating of distal femur fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2016;30:403-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 41. Moreta J, Aguirre U, De Ugarte OS, Jáuregui I, Martínez-De Los Mozos JL. Func-tional and radiological outcome of periprosthetic femoral fractures after hip arthro-plasty. Injury 2015;46:292-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 42. Eickhoff AM, Cintean R, Fiedler C, Gebhard F, Schütze K, Richter PH. Analysis of partial weight bearing after surgical treatment in patients with injuries of the lower extremity. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2022;142:77-81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 43. Vasarhelyi A, Baumert T, Fritsch C, Hopfenmüller W, Gradl G, Mittlmeier T. Partial weight bearing after surgery for fractures of the lower extremity–is it achievable? Gait Posture 2006;23:99-105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 44. Bentler SE, Liu L, Obrizan M, Cook EA, Wright KB, Geweke JF, et al. The aftermath of hip fracture: Discharge placement, functional status change, and mortality. Am J Epidemiol 2009;170:1290-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 45. Mobily PR, Kelley LS. Iatrogenesis in the elderly. Factors of immobility. J Gerontol Nurs 1991;17:5-11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 46. Osnes EK, Lofthus CM, Meyer HE, Falch JA, Nordsletten L, Cappelen I, et al. Con-sequences of hip fracture on activities of daily life and residential needs. Osteoporos Int 2004;15:567-74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]