Successful management of osteopetrotic subtrochanteric fractures requires careful implant selection, modified surgical techniques, and anticipation of intraoperative challenges to achieve good outcomes.

Dr. Kishore Parihar, Department of Orthopaedics, Shri Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi Memorial Medical College, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India. E-mail: drkishoreparihar@gmail.com

Introduction: Osteopetrosis is a rare genetic disorder characterized by increased bone density due to defective osteoclast function, leading to brittle bones prone to pathological fractures. The management of fractures in osteopetrotic patients presents unique challenges due to extreme bone hardness, narrow medullary canals, and increased risk of non-union or implant failure.

Case Report: We present two cases of pathological subtrochanteric femoral fractures in young female patients with osteopetrosis. The first case involved a 30-year-old female with bilateral subtrochanteric fractures, managed surgically with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) using a distal femur locking plate for the complete right-sided fracture, while the left-sided unicortical fracture was treated conservatively. The second case involved a 29-year-old female with a history of prior femoral fractures, presenting with a subtrochanteric fracture of the left femur and a broken plate, which was also managed by Open reduction internal fixation by an anatomical proximal femur plate. Due to the dense sclerotic bone, modifications to standard surgical techniques were necessary, including the use of low-speed drilling with continuous cooling, pre-tapping for screw insertion, and careful implant selection.

Conclusion: The management of osteopetrotic fractures requires a multidisciplinary approach and specialized surgical techniques. Our cases highlight the challenges and successful strategies for treating subtrochanteric fractures in osteopetrosis, contributing valuable insights to the orthopedic management of this rare condition.

Keywords: Osteopetrosis, pathological fracture, subtrochanteric femur fracture, internal fixation, bone sclerosis, orthopedic surgery.

Osteopetrosis, derived from the Greek words for “bone” (“osteo”) and “stone” (“petros”), is a fitting name for a disease in which generalized osteosclerosis identifiable on standard radiographs is pathognomonic. Parallel bands of dense bone can give the appearance often prominent in the pelvis, long bones, phalanges, and vertebrae. Vertebrae can also be uniformly dense or take on a “sandwich vertebrae” or “rugger-jersey” appearance (when a normal-appearing vertebral midbody is sandwiched between dense bands along the superior and inferior endplates). Club-shaped flaring of the metaphysis of long bones with cortical thinning (Erlenmeyer flask bone deformity) and transverse metaphyseal lucent bands reflect a failure of metaphyseal remodeling but are not exclusive to osteopetrosis. Evidence of new or healing fractures may be found, and skull changes can include calvarial and basilar thickening as well as poor sinus development. Because of the wide gamut of pathognomonic radiographic features of osteopetrosis, a skeletal survey is sufficient to make the diagnosis [1]. Despite the increase in bone mass, the mechanical strength of the bones is compromised, predisposing patients to fractures. The overall incidence of these conditions is difficult to estimate, but autosomal recessive osteopetrosis (ARO) has an incidence of 1 in 250,000 births, and autosomal dominant osteopetrosis (ADO) has an incidence of 1 in 20,000 births. Osteopetrotic conditions vary greatly in their presentation and severity, ranging from neonatal onset with life-threatening complications such as bone marrow failure (e.g. classic or “malignant” ARO), to the incidental finding of osteopetrosis on radiographs (e.g. osteopoikilosis). Classic ARO is characterized by fractures, short stature, compressive neuropathies, hypocalcemia with attendant tetanic seizures, and life-threatening pancytopenia. The presence of primary neurodegeneration, mental retardation, skin and immune system involvement, or renal tubular acidosis may point to rarer osteopetrosis variants, whereas the onset of primarily skeletal manifestations, such as fractures and osteomyelitis in late childhood or adolescence is typical of ADO. Osteopetrosis is caused by failure of osteoclast development or function and mutations in at least 10 genes have been identified as causative in humans, accounting for 70% of all cases [2].

In the present case, we report on patients with pathological subtrochanteric femur fractures due to osteopetrosis, an exceedingly rare and complex scenario. The surgical management of these fractures requires specialized approaches due to the bone’s extreme density and brittleness. Standard fixation techniques are often inadequate, and careful consideration must be given to the choice of implants and surgical methods to avoid complications, such as non-union, implant failure, or malunion.

This case report will outline the clinical presentation, diagnostic process, and surgical and pharmacological management strategies employed. By sharing this experience, we hope to contribute to the growing body of literature on osteopetrosis and its orthopedic implications, particularly in the context of challenging fractures, such as subtrochanteric femur fracture.

Case-1

A 30-year-old female presented to the emergency department with complaints of Pain and swelling in the bilateral hip and thigh region and Limited movement of the right hip, especially following a minor fall. The symptoms followed a trivial trauma three days prior to admission There is no prior history of significant illness, surgery, or blood transfusions. She denied any family history of genetic disorders and reported normal childhood development, with no known history of osteopetrosis in her family. Her vitals were within normal range. On local examination Slight swelling of the bilateral hips and thighs. Local tenderness and percussion pain on the right thigh. Limited movement of the right hip with intact flexion and extension of the right knee, ankle, and toes. Good bilateral peripheral pulses and perfusion.

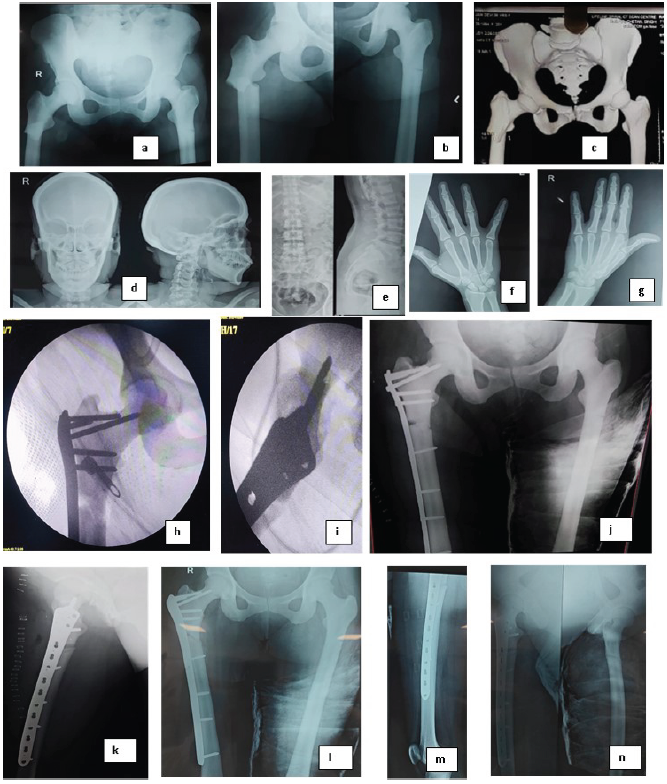

Bilateral hip, pelvic, and thigh xray confirmed subtrochanteric fractures. Complete fracture on the right side and unicortical fracture on the left side [Fig. 1]. X-rays of the skull, hands, and spine showed increased bone density, a characteristic feature of osteopetrosis. [Fig. 1]

Figure 1: Case I. (a and b) X-ray showing subtrochanteric fractures. The right femur demonstrates a complete fracture, while the left femur shows a unicortical fracture with Pelvic bones showing increased bone density characteristic of osteopetrosis, (c) 3D computed tomography of the hips and pelvis showing increased bone density and fracture sites. (d) X-ray skull showing thickened and dense skull bones, (e) X-ray spine showing bone within bone appearance, (f and g) X-ray hand showing increased bone density and loss of corticomedullary differentiation, (h) intraoperative fluorescent images of the fixation of fracture with plate, (i and j) postoperative X-ray of the fixation showing good alignment and fixation, (k-n) 2 months post-operative X-ray showing signs of union at both right and left side.

CT scan Provided a detailed view of the fractures and confirmed the diagnosis of osteopetrosis, showing abnormally dense bone structure in the pelvis, femurs, and other skeletal regions. [Fig. 1]. Complete Blood Count (CBC): Haemoglobin: 11.9 mg/dL, White blood cell count: 11,400 cells/mm³ (84.1% neutrophils, 11.3% lymphocytes), RBCs: 3.98 million cells/mm³, Platelet count: 1.66 lac cells/mm³, Acid phosphatase: 8.20 (elevated, often seen in osteopetrosis) [3], Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): 20 mm/hour, C-reactive protein (CRP): 1.79 mg/L, Parathyroid hormone (PTH): 53.36 pg/mL, Uric acid: 520 µmol/L, Prothrombin time (PT): 15.0 s, INR: 1.12, Liver function tests: SGOT 204 IU/L, SGPT 114 IU/L (mildly elevated)

Surgical management

The right-sided complete fracture was treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) using a femoral locking plate as there was no visible medullary canal on radiographs. The patient received spinal anesthesia and was positioned supine on a traction table. A standard lateral incision was made, and the fracture was reduced, with temporary fixation achieved using bone-holding forceps and K-wires. Fluoroscopic guidance was used to confirm reduction. [Fig. 1]

For definitive fixation, a 13-hole contralateral distal femur (DF) locking plate was selected. Due to the increased bone density characteristic of osteopetrosis, several modifications to standard surgical techniques were necessary. Drilling was performed using a low-speed, high-torque electric drill, with 3.0 mm pilot holes sequentially enlarged to 4.5 mm, using stainless steel bits under continuous saline cooling to prevent overheating of the dense bone. Despite the use of self-tapping screws, we employed a tap for better insertion due to the significantly increased cortical density. The duration of surgery was 2.5 hours, and blood loss was approximately 250 mL.

The procedure was prolonged as technical difficulties were encountered during drilling, with two instances of drill bit breakage. However, the surgery was completed successfully without complications.

Conservative management

The left unicortical subtrochanteric fracture was managed conservatively as it was minimally displaced and biomechanically stable, with intact cortex on one side, allowing functional bracing and expected healing without surgical fixation. Considering the patient’s bilateral pathology, surgery on both sides was avoided to minimize blood loss, operative stress, and risk of iatrogenic fracture.

Postoperative course

Postoperative X-rays confirmed accurate placement of the internal fixation on the right femur, with good apposition and alignment of the fracture fragments [Fig. 1]. The patient’s recovery was uneventful, and she was discharged with instructions for follow-up and rehabilitation. Weight-bearing was started 3 months postoperatively. At the final follow-up at 1 year patient walks without support without any limp.

Case 2

Patient information

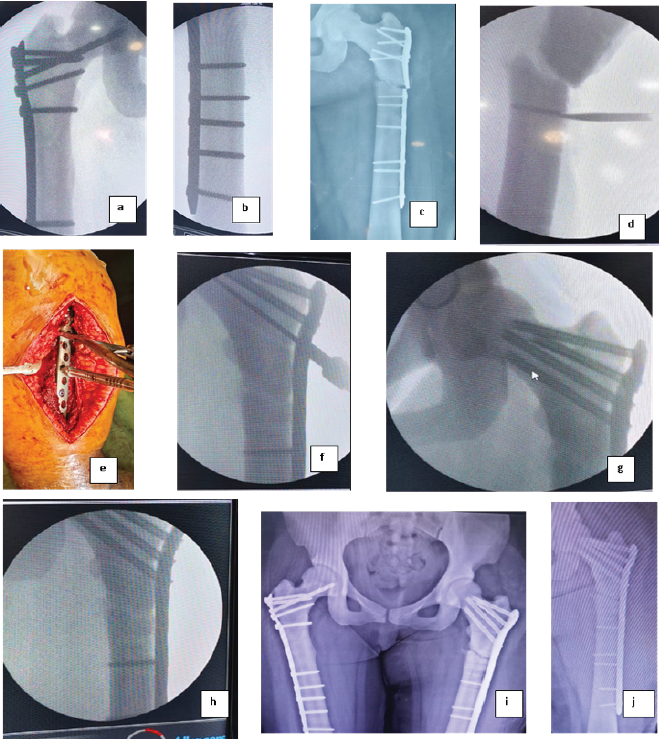

A 29y/F presented to our side with complaints of pain and swelling over left thigh following trivial trauma. She had a history of fracture of shaft femur left side which was managed by operative intervention six months ago. She also had history of surgical fixation of fracture shaft femur right side 2 years back. Her vitals were within normal range. On local examination Slight swelling of the left thigh. Local tenderness and percussion pain on the left thigh. the right hip, knee, ankle, and toes range of motions were normal. Good bilateral peripheral pulses and perfusion. Bilateral hip, pelvic, and thigh xray confirmed subtrochanteric fractures with broken plate and screws in situ left side, and right sided united fracture subtrochanteric fracture with distal femur LCP (Locking Compression Plate) in-situ.

Surgical management

The left complete fracture was treated with removal of plate and screws and open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) using a proximal femoral locking plate as there was no visible medullary canal on radiographs. The patient received spinal anesthesia and was positioned in lateral decubitus [Fig. 2]. A standard lateral incision was made, and screws were removed carefully with the help of a hexagonal screw driver, during the process, on screw head and shaft junction was broken, and that screw was removed with the help of a hollow mill, after that, the fracture was reduced, with temporary fixation achieved using bone-holding forceps and K-wires. Fluoroscopic guidance was used to confirm reduction. [Fig. 2]

Figure 2: Case II. (a and b) Old united subtrochanteric fracture right side fixed with plate, (c) fracture subtrochanteric femur left side with broken proximal humerus interlocking plate osteosynthesis system plate in situ, (d) intraoperative fluorescent imaging showing while removing implant screw head breakage was encountered, (e) Intraoperative positioning (lateral decubitus) and plate placement, (f-h) Intraoperative fluorescent imaging showing proximal femoral anatomical locking plate fixation, (i) Post-operative picture – right sided united fracture subtrochanteric femur with distal femur locking plate in situ and fixed fracture subtrochanteric femur with proximal femoral anatomical locking plate in situ showing good reduction and alignment, (j) Post-operative picture of plate fixation.

For definitive fixation, a long proximal femur anatomical locking plate was selected. This plate comes with cannulated screws in the neck for that the guidewire is inserted with sleeve guidance. In one instance, after guide wire insertion cannulated drill bit was inserted during this process, the guide wire was broken; hence, it was left in situ. [Fig. 2] Due to the increased bone density characteristic of osteopetrosis, several modifications to standard surgical techniques were necessary. Same method of drilling was used as mentioned in case I. Here also we employed a tap for better insertion due to the significantly increased cortical density. The duration of surgery was 3 hours, and blood loss was approximately 300 mL. The surgery was completed successfully without any other complications.

Post-operative course

Post-operative X-rays confirmed accurate placement of the internal fixation on the left femur, with good apposition and alignment of the fracture fragments. The patient’s recovery was uneventful, and she was discharged with instructions for follow-up and rehabilitation. The patient was allowed weight-bearing after 3 months.

Osteopetrosis is a rare genetic disorder that predisposes patients to pathological fractures, particularly in weight-bearing bones such as the femur. The increased bone density, although characteristic of the disease, results in brittle bones that fracture with minimal trauma. Fracture management in osteopetrosis is technically challenging because of the dense, avascular bone and the risk of delayed union or implant failure.

Aslan et al. [4] reported two cases of proximal femoral fixation in osteopetrotic patients and noted frequent drill bit breakage, like our experience. They emphasized the importance of using durable drill systems; accordingly, Kunnasegaran et al. [5] advocated tungsten carbide-tipped drills to minimize intraoperative breakage. However, due to cost constraints, we used conventional steel drill bits with low-speed, high-torque drilling and continuous saline cooling, encountering two instances of breakage. While Aslan et al. [4] employed spongious screws, we utilized tapping before screw insertion to facilitate placement in the sclerotic bone.

Tu et al. [6] described three cases managed by reversed contralateral distal femoral locking compression plates (DF-LCP) in the lateral position with sequential drilling (3 mm to 4.5 mm). In contrast, we performed surgery in the supine position in case I on a traction table, which improved reduction and minimized the need for additional assistance.

Various fixation methods have been described in literature, including intramedullary nailing and plating. Kent et al. [7] demonstrated intramedullary canal creation techniques, particularly suitable for pediatric or upper-limb fractures. However, in our adult patients, the absence of a visible medullary canal and extreme bone sclerosis rendered nailing impractical. Therefore, we opted for locking plate fixation (DF-LCP and PF-LCP), which allowed better contouring, precise screw trajectory, and angular stability. This approach aligns with Sivakumar et al. [8] and Dawar et al. [9], who reported that plate fixation offers reliable union rates, preserves soft tissue biology, and reduces infection risk compared with nailing.

In our series, plate fixation achieved good alignment and uneventful union without complications such as non-union or implant failure, consistent with Bhargava et al. [10]. Our experience, when contrasted with previous literature, suggests that locking plate constructs remain the most practical and biomechanically stable option for subtrochanteric fractures in osteopetrotic adults, especially in settings with limited access to specialized drills and implants.

The case highlights the orthopedic challenges in treating fractures associated with osteopetrosis. Successful surgical management requires specialized techniques to overcome the bone’s abnormal density and hardness. Early diagnosis and a multidisciplinary approach are crucial for the optimal management of such patients.

Osteopetrotic fractures are difficult to treat due to extreme bone density, brittle nature, and high risk of implant failure. Successful management requires careful implant selection, low-speed drilling with cooling, pre-tapping for screws, and anticipation of intraoperative difficulties. With these modifications and a multidisciplinary approach, stable fixation and good functional recovery can be achieved.

References

- 1. Wu CC, Econs MJ, DiMeglio LA, Insogna KL, Levine MA, Orchard PJ, Miller WP, Petryk A, Rush ET, Shoback DM, Ward LM. Diagnosis and management of osteopetrosis: consensus guidelines from the osteopetrosis working group. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2017 Sep 1;102(9):3111-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Stark Z, Savarirayan R. Osteopetrosis. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2009 Dec;4:1-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. CAROLINO J, PEREZ JA, POPA A. Osteopetrosis. American Family Physician. 1998 Mar 15;57(6):1293-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Aslan A, Baykal YB, Uysal E, Atay T, Kirdemir V, Baydar ML, Aydoğan NH. Surgical treatment of osteopetrosis‐related femoral fractures: two case reports and literature review. Case Reports in Orthopedics. 2014;2014(1):891963. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Kunnasegaran R, Chan YH. Use of an industrial tungsten carbide drill in the treatment of a complex fracture in a patient with severe osteopetrosis: a case report. Malaysian Orthopaedic Journal. 2017 Mar;11(1):64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Tu Y, Liu FX, Jia HL, Yang JJ, Lv XL, Li C, Wu JW, Wang F, Yang YL, Wang BM. The Treatment of Subtrochanteric Fracture with Reversed Contralateral Distal Femoral Locking Compression Plate (DF‐LCP) Using a Progressive and Intermittent Drilling Procedure in Three Osteopetrosis Patients. Orthopaedic Surgery. 2022 Feb;14(2):254-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Kent J, Ferguson D. Intramedullary Canal-creation Technique for Patients with Osteopetrosis. Strategies in Trauma and Limb Reconstruction. 2019 Sep;14(3):155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Sivakumar SP, Yamajala S, Vasudeva N, Jayaramaraju D, Shanmuganathan R. Implant strategies for femur fractures in osteopetrosis: Insights from a case series and literature review. Journal of Orthopaedic Reports. 2024 Jun 1;3(2):100284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Dawar H, Mugalakhod V, Wani J, Raina D, Rastogi S, Wani S. Fracture management in osteopetrosis: an intriguing enigma a guide for surgeons. Acta Orthop Belg. 2017 Sep 1;83(3):488-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Bhargava A, Vagela M, Lennox CM. “Challenges in the management of fractures in osteopetrosis”! Review of literature and technical tips learned from long-term management of seven patients. Injury. 2009 Nov 1;40(11):1167-71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]