[box type=”bio”] Learning Point for the Article: [/box]

Even in the rare variants, surgical principles of treatment of monteggia fractures remain the same, where reduction and stabilisation of the ulna fracture should be sufficient to maintain radial stability with favourable outcomes.

Case Report | Volume 8 | Issue 4 | JOCR July – August 2018 | Page 78-81| Amr ElKhouly, J Fairhurst, A Aarvold. DOI: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.1170

Authors: Amr ElKhouly[1], J Fairhurst[1], A Aarvold[1]

[1]Department of Orthopaedics, Southampton Children’s Hospital, United Kingdom.

Address of Correspondence:

Dr. Amr ElKhouly,

Paediatric Orthopedic Department, Southampton University Hospital, Tremona Rd, Southampton SO16 6YD. UK.

E-mail: amrelkhouly@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Giovanni Battista Monteggia first described the Monteggia fracture in 1814. The complexity of this injury was not fully appreciated until it was coined in English as a “Monteggia lesion” by Jose Luis Bado. The Bado classification divides Monteggia fractures into four types of true lesions, plus equivalent variants.

Case Report: This report describes a rare variant where the proximal radial disruption occurs through a Salter-HarrisType II fracture rather than a radial epiphysis dislocation. This is an unstable fracture configuration that has been successfully surgically treated by keeping to the principles of Monteggia fracture reduction.

Conclusion: Even though this is not a classical dislocation of the radial head, this variant with a Salter-Harris fracture should be considered as one.

Keywords: Fracture, Monteggia, Variant, Pediatrics, Orthopedics, PRUJ, Deformity, Radiology.

Introduction

Giovanni Battista Monteggia, a surgical pathologist and public health official in Milan, first described the Monteggia fracture in 1814. The original description is of a “traumatic lesion distinguished by a fracture of the proximal third of the ulna and an anterior dislocation of the proximal epiphysis of the radius”” [1]. The complexity of this injury was not fully appreciated until it was coined in English as a “Monteggia lesion” by Jose Luis Bado [2]. Many classifications have been developed, but Bado’s classification has stood the test of time. It is widely used both clinically, when an acute fracture occurs, and academically, when new variations have been described. The Bado classification divides Monteggia fractures into four types of true lesions, plus equivalent variants [1]. Bado Type I lesions with anterior dislocation of the radial head and concomitant anterior angulation of the ulnar diaphyseal fracture constitute approximately 70% of Monteggia fracture-dislocations[3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. In a retrospective review of 102 children, Olney and Menelaus[8] concluded that Type I equivalent lesions involving the proximal radius accounted for 14% of acute Monteggia lesions, suggesting that equivalent lesions may be more common than previously thought[11,12,13,14]. Although many such equivalent variants have been described in the literature, this report describes a rare Type I variant where the proximal radial disruption occurs anteriorly through a Salter-Harris Type II fracture rather than a radial epiphysis dislocation and a unique treatment method following the principles of management of Monteggia fracture-dislocation Type I.

Case Report

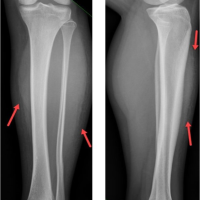

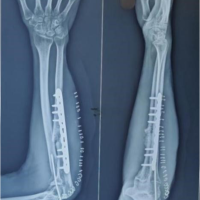

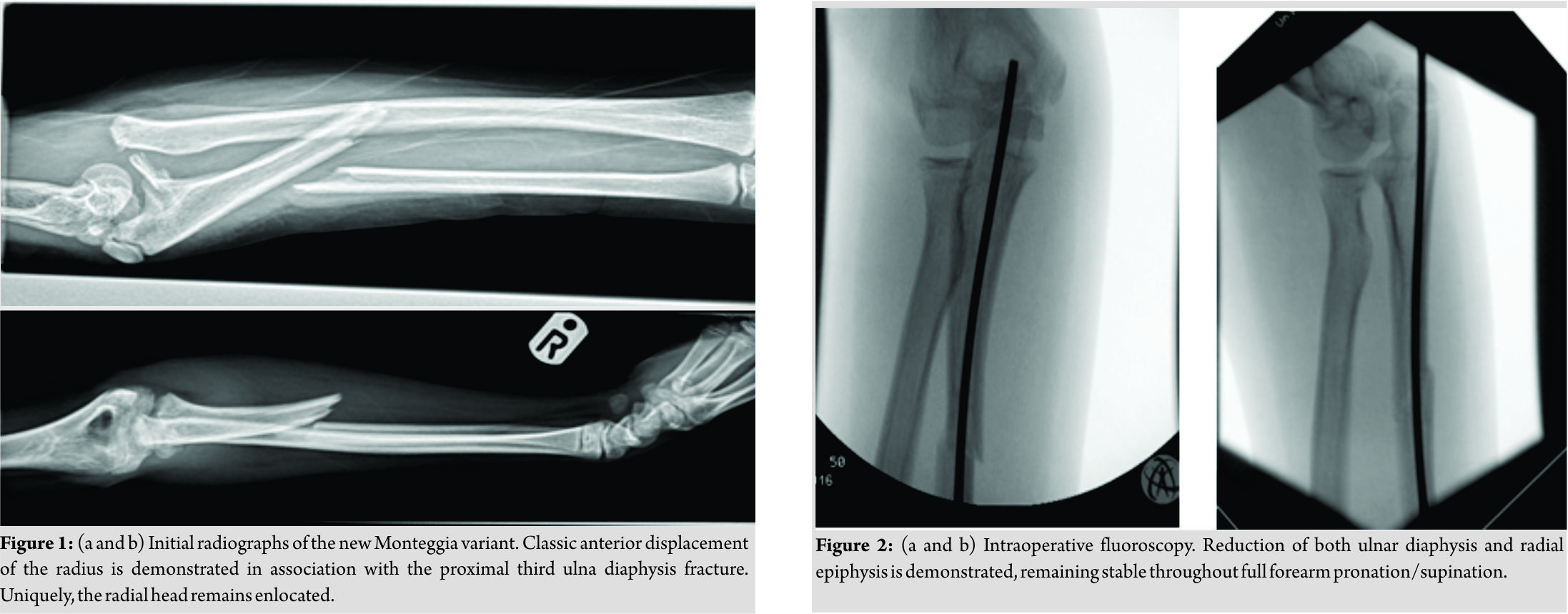

A 10-year-oldright-hand dominant girl had a fall on her outstretched and pronated right hand, having lost balance on her hybrid shoe-roller skates. She presented with a swollen elbow and forearm, with inability to move her elbow. This was a closed injury with no neurovascular deficit. Initial radiographs demonstrated a displaced fracture of the proximal third of the ulna, offended, and with apex anterior angulation of 35°. While the proximal radial shaft was displaced from its normal capitellar alignment, like a classic Monteggia fracture, uniquely the radial epiphysis remained enlocated. This fracture configuration was produced through a displaced Salter-Harris Type II fracture of the proximal radius, with anterior displacement of the metaphysis. The epiphysis was separated from the metaphysis and remained enlocated with the capitellum on all views (Fig. 1). Under general anesthesia, with tourniquet applied but not inflated and the arm on a side board, a trial of manipulation and closed reduction was attempted. Anatomical reduction was initially achieved by focusing on realignment of the ulna fracture. However, both ulna and radial components of the fracture remained grossly unstable. The ulna fracture was stabilized using a 2.5mm titanium elastic nail (Depuy Synthes, Switzerland). Simultaneous anatomical reduction of the Salter-Harris 2 fracture of the proximal radius was achieved. Following stabilization of the ulna fracture, the radial fracture now remained reduced and stable in full range of supination and pronation. Thus, internal fixation of the radius was unnecessary and an above elbow cast was applied (Fig. 2). The patient’s right upper limb was elevated overnight, and she was discharged home the following day. She remained comfortable and had no neurovascular deficit. Repeat radiograph at 1and 4 weeks demonstrated maintained anatomical reduction of both ulna and proximal radius fractures. The cast was removed at 4weeks, with callus evident at both fracture sites, and gentle range of motion exercises was commenced. By 3months, she had regained full flexion/extension of the elbow joint and full supination/pronation of the forearm (Fig. 3). The ulna titanium elastic nail was removed at 6 months postoperatively.

Anatomical reduction was initially achieved by focusing on realignment of the ulna fracture. However, both ulna and radial components of the fracture remained grossly unstable. The ulna fracture was stabilized using a 2.5mm titanium elastic nail (Depuy Synthes, Switzerland). Simultaneous anatomical reduction of the Salter-Harris 2 fracture of the proximal radius was achieved. Following stabilization of the ulna fracture, the radial fracture now remained reduced and stable in full range of supination and pronation. Thus, internal fixation of the radius was unnecessary and an above elbow cast was applied (Fig. 2). The patient’s right upper limb was elevated overnight, and she was discharged home the following day. She remained comfortable and had no neurovascular deficit. Repeat radiograph at 1and 4 weeks demonstrated maintained anatomical reduction of both ulna and proximal radius fractures. The cast was removed at 4weeks, with callus evident at both fracture sites, and gentle range of motion exercises was commenced. By 3months, she had regained full flexion/extension of the elbow joint and full supination/pronation of the forearm (Fig. 3). The ulna titanium elastic nail was removed at 6 months postoperatively.

Discussion

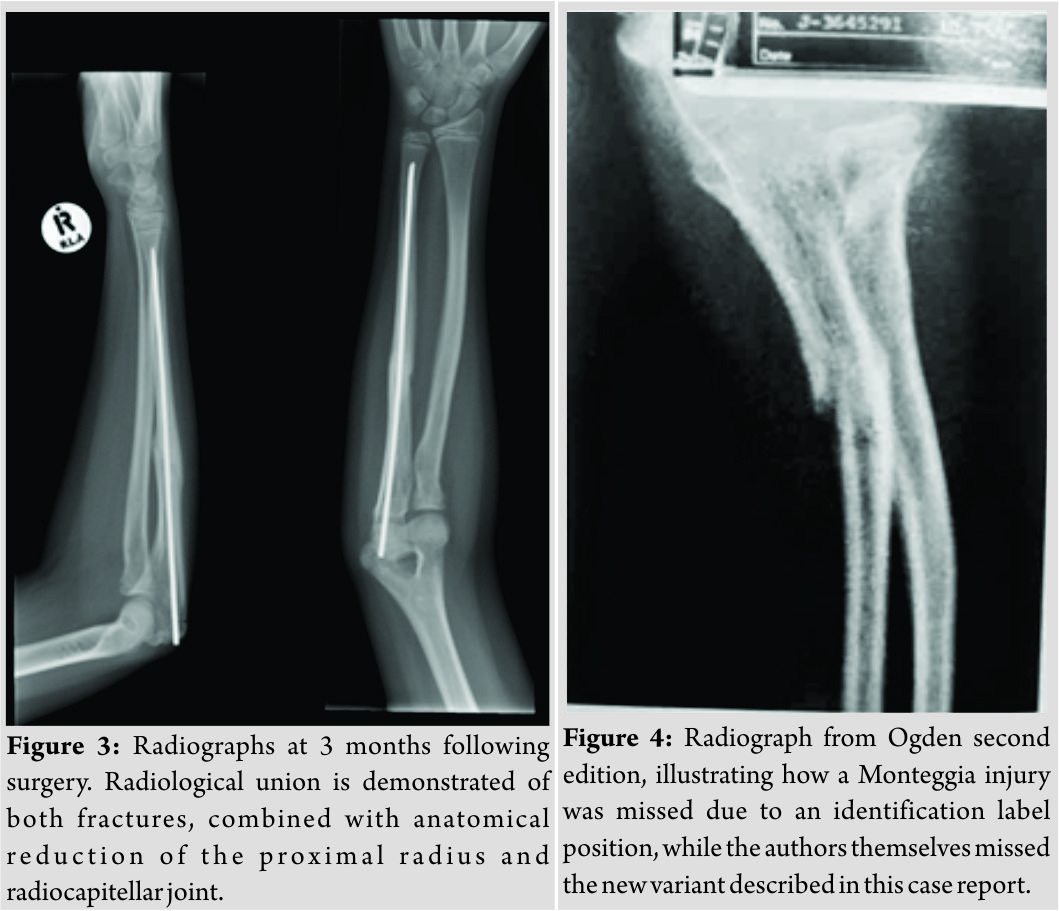

Various reports have shown that the Monteggia fracture dislocation is a rare entity in children in general. Originally Monteggia described these rare injuries based on the pattern of fractures found in adult cadaveric specimens[1]. This might shed some light on the absence of a separate classification system for these lesions in the pediatric population and explain why this pediatric fracture variant was not described in the original classification. Based on the Bado classification, a true Type I lesion is described as an anterior dislocation of the radial head with a fracture of the ulna diaphysis, with most Monteggia injuries in children being of this type (approximately 70% in most series) [1, 15]. Bado Type I equivalents are described in Rockwood and Wilkins. These include an isolated anterior radial head dislocation with minimal plastic deformation of the ulna, a fractured ulnar diaphysis with a fracture of the proximal radius diaphysis, or fracture of the olecranon [1]. None of these descriptions have encompassed the variant described in this case report, where there is a fracture of the ulna shaft together with a displaced Salter-Harris type of fracture of the proximal radial epiphysis. To the best of our knowledge, this variant was not clearly described in the literature either. The Monteggia equivalent lesions expanded in the literature by different authors[10,16,17]consisting of various radiographic patterns of fracture-dislocations about the elbow and forearm, and Caterini et al.[18] reported three cases of olecranon fracture associated with radial head dislocation, but no cases with concomitant radial neck fracture were found. Kamali et al.[12]presented an injury pattern comprising of radial head displacement, fracture of the radial neck, and proximal third ulna shaft fracture without olecranon involvement. Of the 14 Monteggia equivalent lesions involving the proximal radius and ulna presented by Olney and Menelaus[8,16],the three Type I equivalent lesions, as described with schematic depictions in the original paper, were as follows, the first one was dislocation of the upper end of the radius with bowing of the ulna, the second one was fracture of the ulnar shaft and head or neck of the radius and the last one was fracture of ulnar shaft, anterior and lateral dislocation of the upper end of the radius plus fracture of the olecranon`. Interestingly, a particular radiograph in Ogden Second Edition, 1990, p.484 is used to demonstrate a missed Monteggia fracture [19]. A patient’s name is printed on the radiograph over the proximal radius, thus illustrating how easily a Monteggia fracture can be missed with suboptimal imaging. Interestingly, this injury is a Salter-Harris 2 fracture of the proximal radius, as described in this report. Paradoxically, the authors have identified this case as a Monteggia fracture but missed reporting this as a previously undescribed variant (Fig. 4). The recommended management for most Monteggia and equivalent lesions in children is non-operative as long as the dislocated radial head can be reduced and remains stable[20, 21, 22]. According to Bado[20],“fresh” Monteggia Type I and equivalent lesions should be treated by closed reduction with a supination maneuver. Although early diagnosis and closed reduction of Type I Monteggia lesions usually yield good-to-excellent results[4, 5, 9, 10, 20, 22, 23], Olney and Menelaus[8] suggested that TypeI equivalent injuries may require open reduction and internal fixation. Three case reports were encountered in the literature with ulnar diaphyseal fracture and proximal radial fracture and presented three different treatment protocols, Soin et al presented a case report of a 6-year old child where the pattern of the fracture was described as a midshaft fracture of the ulna and a transverse fracture through the neck of the radius, where it was opted to treat it conservatively with an outcome of loss of 20° of pronation[24]. Faundez et al.[25] described a similar pattern of fracture dislocation in a 6 years’ old, however due to concerns with dislocation of the radial head, opted to hold the radial head temporarily with K-wires, fix the ulna fracture with flexible nail, and maintain the radial position with another flexible nail with an end result of loss of 10° of supination. In a similar fashion, Reina et al. have another case report[26], where a diaphyseal ulnar fracture and a proximal physeal injury with a posteriorly displaced proximal radius in a 13-year-old adolescent were managed surgically, the ulnar fracture was fixed with plate osteosynthesis, but the radial dislocation underwent an open reduction and fixation with an elastic nail with loss of 20° of supination. In our case report, surgical principles of treatment of Monteggia fractures were maintained. We were successful to reduce the proximal radial fracture dislocation using the supination maneuver without requiring to perform an open reduction or further stabilization in contrast to what was suggested by Olney or performed in other case reports. This has proven to maintain the stability of the fracture pattern with no compromise to the range of movement of the forearm which was regained fully, an advantage that was not achieved in all three case reports published with similar fracture pattern but different stabilization strategy. Despite this being a SH2 fracture rather than a radial head dislocation, anatomical reduction of the radial fracture was achieved by reducing and fixing the ulna fracture. This proved to be of key importance in maintaining radial stability in full range of movement in this, now clearly described, variant of a Type I Monteggia lesion.

Conclusion

Combined fracture of the ulna with a Salter-Harris fracture of the proximal radius is a previously unclearly reported variant of the Monteggia fracture-dislocation. This is an unstable fracture configuration that has been successfully surgically treated by keeping to the principles of Monteggia fracture reduction. Even though this is not a classical dislocation of the radial head, this variant with a Salter-Harris fracture should be considered as one.

Clinical Message

This new Monteggia Type I variant is an unstable fracture dislocation. Even though it is a Salter-Harris fracture rather than a classical radial head dislocation, it should be considered as one. Accordingly, surgical principles of treatment of Monteggia fractures should be maintained, where reduction and stabilization of the ulna fracture should be sufficient to maintain radial stability with favorable final outcomes.

References

1. Beaty JH, Kasser JR. Monteggia fracture-dislocation in children. In: Rockwood and Wilkins’ Fractures in Children. 6th ed. Riverwoods, IL: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006. p. 447-551.

2. Bado JL. The Monteggia Lesion. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1962.

3. Dormans JP, Rang M. The problem of monteggia fracture-dislocations in children. Orthop Clin North Am 1990;21:251-6.

4. Letts M, Locht R, Wiens J. Monteggia fracture-dislocations in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1985;67:724-7.

5. Wiley JJ, Galey JP. Monteggia injuries in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1985;67:728-31.

6. Bryan RS. Monteggia fracture of the forearm. J Trauma 1971;11:992-8.

7. Fowles JV, Sliman N, Kassab MT. The monteggia lesion in children. Fracture of the ulna and dislocation of the radial head. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1983;65:1276-82.

8. Olney BW, Menelaus MB. Monteggia and equivalent lesions in childhood. J PediatrOrthop 1989;9:219-23.

9. Peiro A, Andres F, Fernandez-Esteve F. Acute monteggia lesions in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1977;59:92-7.

10. Reckling FW. Unstable fracture-dislocations of the forearm: Monteggia and galeazzi lesions. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1982;64:857-63.

11. Fahmy NR. Unusual monteggia lesions in children. Injury 1981;12:399-404.

12. Kamali M. Monteggia fracture: Presentation of an unusual case. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1974;56:841-3.

13. Tibone JE, Stoltz M. Fractures of the radial head and neck in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981;63:100-6.

14. Wright PR. Greenstick fracture of the upper end of the ulna with dislocation of the radio-humeral joint or displacement of the superior radial epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1963;45:727-31.

15. Williams HL, Thayur RM, Sinha A. Type III monteggia injury with ipsilateral type II salter harris injury of the distal radius and ulna in a child, a case report. BMC Res Notes 2014;7:156.

16. Ruchelsman D, Klugman JA, Madan SS, Chorney GS. Anterior dislocation of the radial head with fractures of the olecranon and radial neck in a young child. A monteggia equivalent. Fracture-dislocation variant. J Orthop Trauma 2005;19:428-31.

17. Ramsey RH, Pedersen HE. The Monteggia fracture-dislocation in children. JAMA 1962;182:1091-3.

18. Caterini R, Farsetti P, D’Arrigo C, Ippolito E. Fractures of the olecranon in children. Long-term follow-up of 39 cases. J PediatrOrthop B 2002;11:320-8.

19. Ogden J. Skeletal Injury in the Child. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA, USA: W.B. Saunders; 1990.

20. Bado JL. The monteggia lesion. Clin Orthop 1967;50:71-86.

21. Speed JS, Boyd HB. Treatment of fracture of ulna with dislocation of head of radius: Monteggia fracture. JAMA 1940;125:1699.

22. Tompkins DG. The anterior monteggia fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1971;53-A:1109-14.

23. Papavasiliou VA, Nenopoulos SP. Monteggia-type elbow fractures in childhood. Clin Orthop 1988;233:230-3.

24. Soin B, Hunt N, Hollingdale J. An unusual forearm fracture in a child suggesting a mechanism for the monteggia injury. Injury 1995;26:407-8.

25. Faundez AA, Ceroni D, Kaelin A. An unusual monteggia type-I equivalent fracture in a child. JBJS Br 2003;85:584-6.

26. Reina N, Laffosse JM, Abbo O, Accadbled F, Bensafi H, Chiron P, et al.Monteggia equivalent fracture associated with salter i fracture of the radial head. J PediatrOrthop B 2012;21:532-5.

|

|

|

| Dr. Amr ElKhouly | Dr. J Fairhurst | Dr. A Aarvold |

| How to Cite This Article: ElKhouly A, Fairhurst J, Aarvold A. The Monteggia Fracture: literature review and report of a new variant. Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports 2018. Jul-Aug; 8(4): 78-81. |

[Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] [XML]

[rate_this_page]

Dear Reader, We are very excited about New Features in JOCR. Please do let us know what you think by Clicking on the Sliding “Feedback Form” button on the <<< left of the page or sending a mail to us at editor.jocr@gmail.com