En bloc surgical excision is a practical and effective option for treating small arteriovenous malformations in the foot.

Dr. Marlon M Mencia, Department of Clinical Surgical Sciences, Port of Spain General Hospital, Trinidad and Tobago. E-mail: mmmencia@me.com

Introduction: Arteriovenous malformations (AVM) are developmental vascular malformations consisting of abnormal arteriovenous shunts surrounding a central nidus. These lesions are relatively uncommon, comprising just 7% of all benign soft-tissue masses. Most AVMs occur in the brain, neck, pelvis, and lower extremity and rarely manifest in the foot. When they do form in the foot, non-specific pain and the absence of clinical features contribute to the high rate of misdiagnosis on initial presentation. Although surgical excision combined with embolotherapy has emerged as the preferred treatment for large AVM, controversy exists over the best treatment for small lesions in the foot.

Case Presentation: A 36-year-old Afro-Caribbean man was referred to the clinic with a 2-year history of increasing pain in his forefoot, affecting his ability to stand or walk comfortably. There was no history of trauma, and despite changing his footwear, the patient continued to have significant pain. Clinical examination was unremarkable except for mild tenderness over the dorsum of his forefoot, and radiographs were normal. A magnetic resonance scan reported an intermetatarsal vascular mass but could not exclude malignancy. Surgical exploration and en bloc excision confirmed the mass to be an AVM. One year post-surgery, the patient remains pain-free with no evidence of recurrence.

Conclusions: The rarity of AVM in the foot, combined with normal radiographs and non-specific clinical signs, contributes to the long delay in diagnosing and treating these lesions. Surgeons should have a low threshold for obtaining magnetic resonance imaging in cases of diagnostic uncertainty. En bloc surgical excision is an option for treating small suitably located lesions in the foot.

Keywords: Arteriovenous malformation, foot, magnetic resonance imaging, en bloc excision, embolotherapy.

Structurally, an arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is a developmental malformation consisting of a mass of abnormal shunts between arteries and veins [1]. These lesions are low resistance and high flow vascular channels characterized by a central nidus of interconnected arteries and veins without an intermediate capillary network. Congenital maldevelopment is the most common cause of an AVM, although other causes including trauma have been reported [2,3,4]. These lesions are formed during fetal development as a result of an abnormal differentiation of the vascular structures. The morphology of the resulting lesion is determined by the point of failure during differentiation [1]. Although present at birth, these lesions are generally asymptomatic but may grow during puberty causing symptoms. AVMs are relatively uncommon, making up just 7% of all benign soft-tissue masses [5]. The incidence is estimated at 1/100,000 population per year with a prevalence of 10/100,000. Both males and females are affected in equal numbers, with peak onset of symptoms between 35 and 40 years of age and there appears to be no ethnic or racial bias [5]. Although they may form anywhere in the body, AVMs are most commonly found in the brain, neck, pelvis, and lower extremity. Occurrence in the foot is extremely rare, with only a few case reports and small case series reported in the literature [6,7,8,9]. Because of their infrequency and unpredictable clinical features, when AVMs do occur, they are commonly misdiagnosed [6]. Several imaging techniques may be used to diagnose AVMs; however, the heterogenicity of the lesions makes definitive diagnosis difficult [7]. To date, treatment options for AVMs have revolved around the use of embolotherapy only or combined with surgical excision. Moreover, while these methods have been used successfully in several areas of the body, controversy surrounds the best strategy to manage small lesions found in the foot [6,7,8,10]. Surprisingly, surgical excision for the treatment of AVMs in the foot has been rarely documented and there are only two published case reports in the literature [7,9]. We present a case of an AVM in the foot of a 36-year-old man which remained undiagnosed for 2 years but was eventually successful treated by en bloc surgical excision.

A 36-year-old male was referred to our foot and ankle clinic by his general practitioner with a 2-year history of pain over the dorsum of his left foot. He described the pain as a dull ache which was made worse on prolonged standing or walking. The patient could not recall any previous injury, and despite simple analgesics and a change of shoes, he continued to have significant pain. His medical history was unremarkable and he was in excellent general health. On initial presentation, we noted an obvious antalgic gait, while examination of the foot showed no skin changes or swelling. Our only positive physical finding was mild tenderness over the dorsum along the second and third metatarsals; otherwise, there was a full range of movement at all joints and a normal neurovascular examination. Several radiographs taken over the prior 2 years were regarded as normal. We requested a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, which revealed diffuse high T2 and low T1 signals in the first and second dorsal interossei muscles without a discrete mass. The appearance was reported as being consistent with a vascular malformation but could not exclude a liposarcoma or synovial sarcoma (Fig. 1). A biopsy was recommended, but with the possibility that this was a vascular malformation, we decided that exploration and complete excision would be the most appropriate treatment method. In the operating theatre, we made a 5 cm longitudinal incision over the dorsum of the foot in line with the second metatarsal. The first and second dorsal interosseous spaces were readily visualized and the muscle appeared edematous and inflamed. We retracted the muscle fibers of the second dorsal interosseous space to reveal an underlying mass of highly vascular tissue. Although there was no distinct capsule, we easily separated the mass from the surrounding muscle. No single feeding vessel was identified, but there were many vascular channels that required hemostasis. We excised the lesion en bloc and sent the specimen to pathology. Exploration of the adjacent interosseous space revealed no gross abnormalities, and after meticulous hemostasis was achieved, we closed the tissues in layers. The histopathology report stated that the specimen consisted of fragments of skeletal muscle, adipose tissue and haphazardly arranged, dilated, and thick-walled branching blood vessels in continuity with the muscle fibers. Few inflammatory cells were found within the muscle, and the vascular plexi were associated with hemosiderin pigment material. The report indicated that the lesion was completely excised, and the findings were highly suggestive of an intramuscular AVM (Fig. 2).

Two weeks after surgery, we reviewed the patient in our clinic. His incision was well healed, and we allowed him to return to work without any restrictions (Fig. 3). At his annual follow-up appointment, the patient confirmed that he was pain-free with only mild discomfort after prolonged standing or walking. Physical examination was unremarkable, with no signs of recurrence.

AVMs are high flow lesions caused by a failure of vascular differentiation during embryogenesis, resulting in direct communication between arteries and veins without an intervening capillary bed. Although most AVMs occur in isolation, multiple lesions may be associated with several congenital syndromes [7]. AVMs can occur throughout the body but are typically found in the brain, pelvis, and lower extremities. These lesions display marked heterogeneity, making classification a challenging task. However, since 2014, the classification system developed by the International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies (ISSVA) has been most widely used. The ISSVA subdivides these vascular malformations into four categories based on their predominant histological components, vessel involvement, and clinical expression [11].

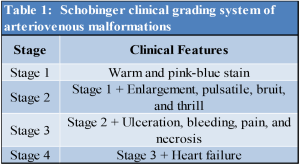

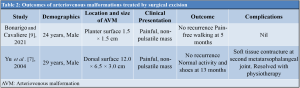

It is estimated that AVMs comprise 7% of all benign soft-tissue tumors, and despite their potential to occur in all regions of the body, these lesions are very rarely found in the foot. The literature search revealed only a few case reports and small case series on AVMs in the foot [6,7,8,9,10,12,13,14,15]. The largest study reported by Hyun et al. included only 29 patients [8]. These small studies highlight the rarity of AVM’s in the foot and the deficiency of the current literature. AVM of the foot may mimic common podiatric conditions leading to a delay in diagnosis [9]. Most reveal their presence by causing pain, skin discolouration, ulceration, or a mass. Skin changes which include macules, nodules, and plaques, have been reported in up to 50% of AVMs. The uncommon finding of a palpable thrill or audible bruit is thought to be the most clinically defining characteristic of an AVM. Although most lesions are quiescent; symptoms may be caused by trauma or during periods of adolescent growth. The Schobinger classification, a clinical grading system, can be used to estimate disease progression and is predictive of treatment success (Table 1) [16]. Hyun et al. reported that pain was the most common presenting symptom in AVMs of the foot, occurring in 83% of patients, although pain was rarely the only symptom [8]. We searched the PubMed database using a combination of the following keywords: “AVM,” “ankle,” and “foot.” The titles and abstracts of all resultant search articles were screened. Studies describing the presentation and treatment of AVMs of the foot were eligible for inclusion and the full text was reviewed when available. We found 19 studies (15 case reports and four case series) with 53 patients. The presenting symptoms and signs of all patients are shown in (Fig. 4). The data show that pain combined with other signs and symptoms was the most common presenting complaint in 77% of patients. However, pain alone was a rare presentation seen in just two patients (4.0%) [6,14]. A retrospective multicenter study postulated that the initial manifestations of distal AVMs could be discreet and non-specific, contributing to a delayed diagnosis [17]. Our patient presented with only vague foot pain, which is likely to be partially responsible for the late diagnosis. Several imaging methods are used to investigate AVMs arising in the foot. Conventional radiographs are typically the first investigative tool, and although not diagnostic, may reveal evidence of increased soft-tissue shadowing or bony erosion secondary to an underlying vascular malformation [14]. Color Doppler ultrasound can detect the bi-directional vascular flow in arteries and veins but is limited by being largely user-dependent. Computed tomography with intravenous contrast is a sensitive investigation producing high-resolution images, although it exposes the patient to high levels of ionizing radiation. Standard MRI allows good tissue delineation and can detect vascular anomalies but may not accurately diagnose an AVM [14]. However, magnetic resonance angiography can separate vascular lesions into low flow lesions characteristic of a hemangioma and high flow lesions found in AVMs and arteriovenous fistulas (AVF). The single connection found in an AVF differentiates it from the multiple connections more characteristic of AVM. Despite greater image resolution and lesion morphology, non-invasive studies are not considered diagnostic. Digital subtraction angiography, which provides high-resolution images of the vascular architecture, is now considered the gold standard investigative method for diagnosing AVMs of the lower limb [5,10]. The majority of AVMs in the foot are treated with embolotherapy either as definitive treatment or preoperatively combined with surgical excision [1,8,10,13,15]. Treatment is typically indicated for pain, functional impairment, or cosmetic deformity [1]. While the goal of treatment involves complete removal of the nidus, the limited blood supply to the region must be respected. Minimally invasive embolotherapy requires a high level of technical skill and is becoming more commonly applied to AVMs in the foot [18]. In the largest series to date, of the 29 patients included in the study, seven patients (24%) had complete resolution of symptoms, and 17 patients (59%) had partial resolution. The total complication rate was 72%, with one patient requiring a below-knee amputation [8]. Skin necrosis was the most common minor complications occurring in 10 (35%) patients. The authors hypothesize that their high complication rate was due to the presence of fine and tortuous arteries in the foot and the technical complexities involved in catheter placement [15].

In treating AVMs, reconstructive flap surgery may be combined with embolotherapy and surgical excision or as a salvage option for soft-tissue defects [4,19]. Sural and lateral supramalleolar flaps are the most commonly used fasciocutaneous flaps to treat soft-tissue defects in the foot and ankle [20,21]. Sural flaps are more popular, having the advantage of faster elevation, technical simplicity, and easier closure than lateral supramalleolar flaps. However, lateral supramalleolar flaps provide superior distal coverage with an extended variation shown to be a reliable choice for very distal foot coverage [12]. One major advantage of flap surgery is that they do not preclude free tissue transfer as a secondary procedure in the event of flap necrosis. Surgical excision of an AVM may be an attractive option but carries the inherent risks of recurrence and excessive bleeding. In the foot and ankle, proximity to the joints, tendons, and ligaments risk damage to these structures, while wide excision can lead to exposure of the underlying tissues requiring additional procedures to achieve soft-tissue cover [9]. The most suitable AVMs for surgical excision are, perhaps, small and well-defined lesions located on the dorsum of the foot [1]. Notwithstanding the appeal of surgical excision, only two case reports in the literature describe this treatment method (Table 2). Both patients were young men in their 20 s and recovered fully after surgery with no evidence of recurrence. Our patient had several characteristics in common with these two patients, making him a suitable candidate for surgical excision.

AVMs in the foot are a rare occurrence, and it is, therefore, reasonable to assume that many orthopedic surgeons will never encounter them during a career. Our patient presented with vague foot pain, no hard clinical signs, and normal radiographs. Low clinical suspicion combined with non-specific symptoms contributed to the delayed diagnosis in this case. Our use of MRI is justified since it is an invaluable tool in diagnosing soft-tissue tumors; however, it must be remembered that it may not accurately diagnose vascular lesions. There is a paucity of robust scientific evidence to guide surgeons when treating small AVMs occurring in the foot. Percutaneous embolotherapy is an option, although the specialized technical skill needed for safe execution of the procedure make widespread adoption unlikely, and in our local setting, this option is not currently available. Surgical excision of small AVMs of the foot offers the potential for cure and has been used successfully. The technical skill required is within the proficiency range of a general orthopedic surgeon and does not require subspecialist referral. After a thorough vascular assessment, we recommend that orthopedic surgeons consider the option of surgical excision for the treatment of small AVMs in the foot.

An AVM may uncommonly cause non-specific foot pain. Magnetic resonance angiography allows differentiation from other vascular tumors and confirms the diagnosis. En bloc surgical excision is an effective treatment for suitably located lesions.

References

- 1.Rosen RJ, Riles TS, Berenstein A. Congenital Vascular Malformations. Philadephia, PA: Saunders; 1985. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Kellerhouse LE, Ranniger K. Congenital arteriovenous malformation of the foot. Am J Roentgenol Radium Therm Nucl Med 1969;105:877-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Waterson KW, Shapiro L, Dannengerg M. Developmental arterio venous malformation with secondary angiodermatitis report of a case. Arch Dermatol 1969;100:297-302. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Kadono T, Kishi A, Onishi Y, Ohara K. Acquired digital arterio- venous malformation: a report of six cases. Br J Dermatol 2000;142:362-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.National Organisation for Rare Disorders. Arteriovenous Malformation; 2013. Available from: https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/arteriovenous-malformation. Last accessed February 10, 2022. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Schick FA. A nonsurgical approach to arteriovenous malformation of the foot a case report. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2015;105:377-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Yu GV, Brarens RM, Vincent AL. Arteriovenous malformation of the foot: A case presentation. J Foot Ankle Surg 2004;43:252-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Hyun D, Do YS, Park KB, Kim DI, Kim YW, Park HS, et al. Ethanol embolotherapy of foot arteriovenous malformations. J Vasc Surg 2013;58:1619-26. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Bonarigo EM, Cavaliere RG. surgical management of arteriovenous malformation in the foot: A case study. J Foot Ankle Surg 2021;60:146-51. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Igari K, Kudo T, Toyofuku T, Jibiki M, Inoue Y. Surgical treatment with or without embolotherapy for arteriovenous malformations. Ann Vasc Dis 2013;6:46-51. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies. ISSVA Classification for Vascular Anomalies; 2018. Available from: https://www.issva.org/userfiles/file/issva-classification-2018.pdf. Last accessed December 13, 2021. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Agir H, Sen C, Onyedi M. Extended lateral supramalleolar flap for very distal foot coverage: A case with arteriovenous malformation. J Foot Ankle Surg 2007;46:310-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Kunze B, Kuba T, Ernemann U, Miller. Arteriovenous malformation: An unusual reason for foot pain in children. Foot Ankle Online J 2009;2:1. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.14. Mohammad HR, Bhatti W, Pillai A. An unusual presentation of arteriovenous malformation as an erosive midfoot lesion. J Surg Case Rep 2016;2016:rjw146. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Yakes W, Huguenot M, Yakes A, Continenza A, Kammer R, Baumgartner I. Percutaneous embolization of arteriovenous malformations at the plantar aspect of the foot. J Vasc Surg 2016;64:1478-82. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Schobinger RA. "Diagnostic and therapeutic options for peripheral angiodysplasia.” Helv Chir Acta 1971;38:213-20. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Guillet A, Connault J, Perrot P, Perret C, Herbreteau D, Berton M, et al. Early symptoms and long-term clinical outcomes of distal limb's cutaneous arterio-venous malformations: A retrospective multicentre study of 19 adult patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2016;30:36-40. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Cho SK, Do YS, Kim DI, Kim YW, Shin SW, Park KB, et al. Peripheral arteriovenous malformations with a dominant outflow vein: Results of ethanol embolization. Korean J Radiol 2008;9:258-67. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Bryant RS, Russell EJ, Curtin JW. Combined treatment arteriovenous malformations by transarterial microembolization and surgery. Am J Surg 1988;54:637-42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Pinsolle V, Reau AF, Pelissier P, Martin D, Baudet J. Soft tissue reconstruction of the distal lower leg and foot: Are free flaps the only choice? Review of 215 cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2006;59:912-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Touam C, Rostoucher P, Bhatia A, Oberlin C. Comparative study of two series of distally based fasciocutaneous flaps for coverage of the lower one-fourth of the leg, the ankle, and the foot. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;107:383-92. [Google Scholar | PubMed]