The unusual site of presentation of a tumor leading to a diagnostic challenge and delay in treatment.

Dr. Nirvin Paul, Department of Trauma Surgery, AIIMS Rishikesh, Uttarakhand – 249203, India. E-mail: drnirvinpaul@gmail.com

Introduction: Osteoid osteoma is a common benign bone tumor affecting young adults with the typical clinical and radiological presentation when arising from common locations. However, when they arise from unusual locations like intra-articular regions the diagnosis may be confusing thereby leading to delay in diagnosis and appropriate management. Here we present a case with an intra-articular osteoid osteoma of the hip involving the anterolateral quadrant of the femoral head.

Case Report: An active 24-year-old man, with no relevant or significant medical history presented with progressive left hip pain radiating to the thigh for the past 1 year. There was no significant history of trauma. His initial symptoms were dull aching groin pain which worsened over weeks, associated with night cries, and loss of weight and appetite.

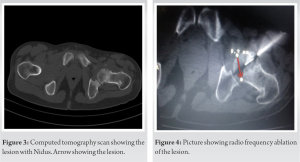

Conclusion: The unusual site of presentation led to a diagnostic challenge and caused a delay in diagnosis. Computed tomography scan is the gold standard to detect osteoid osteoma and radiofrequency ablation can be used as a reliable and safe modality of the treatment for intra-articular lesions.

Keywords: Osteoid osteoma, hip monoarthritis, benign tumor, Nidus, radiofrequency ablation

Osteoid osteoma is a solitary, benign osteoblastic lesion of the bone comprising 10–12% of all benign tumors and 3% of all primary bone tumors [1]. It was first described by Bergstrand in 1930 and later characterized by Jaffe as an entity in 1935 [2]. It is most common in young adults in the second and third decade affecting males more than females (3:1). In majority of the cases, osteoid osteoma is commonly seen in cortico-diaphyseal regions of the long bones such as the femur and tibia with proximal femur being the most common location [3]. A history of nocturnally aggravating and salicylate-responding pain is characteristic of this tumor. It has been reported that the location of osteoid osteoma is rare in intra-articular regions [4]. When arising from intra-articular regions, osteoid osteoma may present with clinical features that mimic inflammatory mono arthritis or synovitis with atypical radiographic findings such as lack of periosteal reaction and sclerosis [5], this, in turn, may lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment. Here, we report on the case of a 24 year old man with intra-articular osteoid osteoma involving the left femoral head, initially not detected on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

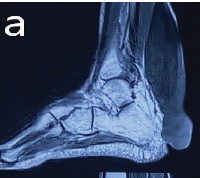

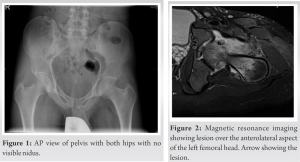

An active 24-year-old man, with no relevant or significant medical history presented with progressive left hip pain radiating to the left thigh for the past 1 year. There was no significant history of trauma. His initial symptoms were dull aching groin pain which worsened over weeks, associated with night cries, and loss of weight and appetite. Roentgenogram was done which was unremarkable (Fig. 1). Initial work-up included an MRI of the hip which showed synovitis and marrow edema without fracture. Based on the clinical features and MRI findings, he was treated with 6 months of anti-tubercular therapy. Despite anti-tubercular treatment, his symptoms did not improve. When he presented to us, he had hip stiffness and pain in the groin, and anterior thigh pain which worsened when he walked. Physical examination revealed antalgic gait and reduced hip range of motion in all planes associated with spasms and pain. There was tenderness on deep palpation in the left groin and the straight leg raising test is negative. Neurological examination found no abnormality. Our initial differential diagnosis included intrinsic hip pathologies like avascular necrosis and tuberculous synovitis. Complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and Creactive protein were within normal limits and an open synovial biopsy of the left hip was performed for obtaining samples for culture and tissue biopsy. All the cultures were negative and the biopsy showed mild to moderate chronicsynovitis with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates. To exclude immune-mediated arthritis, rheumatologic evaluation was done which included serologic studies and MRI of bilateral sacroiliac joints. Serological studies were unremarkable and MRI showed a well-defined T1 hypo intense, short tau inversion recovery hyperintense lesion with a thick sclerotic hypo intense rim, in the anterolateral cortex of the left femoral head with marrow edema and no significant periosteal reaction. There was moderate left hip joint effusion with synovitis (Fig. 2). MRI was followed by limited computed tomography (CT) cuts through the hip joints which showed a well-defined lytic lesion measuring approximately 8 × 6 mm with peripheral sclerotic rim and partly calcified nidus consistent with intracapsular osteoid osteoma (Fig. 3). As the lesion was amendable for the radiological guided procedure, the patient underwent CT-guided Radio Frequency Ablation as an alternative to surgical excision as it avoids the complications associated with surgical exposure of the femoral head, and injury to the capsular vessels, chondral, or osteochondral damage from resection (Fig. 4).

Initial work-up included an MRI of the hip which showed synovitis and marrow edema without fracture. Based on the clinical features and MRI findings, he was treated with 6 months of anti-tubercular therapy. Despite anti-tubercular treatment, his symptoms did not improve. When he presented to us, he had hip stiffness and pain in the groin, and anterior thigh pain which worsened when he walked. Physical examination revealed antalgic gait and reduced hip range of motion in all planes associated with spasms and pain. There was tenderness on deep palpation in the left groin and the straight leg raising test is negative. Neurological examination found no abnormality. Our initial differential diagnosis included intrinsic hip pathologies like avascular necrosis and tuberculous synovitis. Complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and Creactive protein were within normal limits and an open synovial biopsy of the left hip was performed for obtaining samples for culture and tissue biopsy. All the cultures were negative and the biopsy showed mild to moderate chronicsynovitis with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates. To exclude immune-mediated arthritis, rheumatologic evaluation was done which included serologic studies and MRI of bilateral sacroiliac joints. Serological studies were unremarkable and MRI showed a well-defined T1 hypo intense, short tau inversion recovery hyperintense lesion with a thick sclerotic hypo intense rim, in the anterolateral cortex of the left femoral head with marrow edema and no significant periosteal reaction. There was moderate left hip joint effusion with synovitis (Fig. 2). MRI was followed by limited computed tomography (CT) cuts through the hip joints which showed a well-defined lytic lesion measuring approximately 8 × 6 mm with peripheral sclerotic rim and partly calcified nidus consistent with intracapsular osteoid osteoma (Fig. 3). As the lesion was amendable for the radiological guided procedure, the patient underwent CT-guided Radio Frequency Ablation as an alternative to surgical excision as it avoids the complications associated with surgical exposure of the femoral head, and injury to the capsular vessels, chondral, or osteochondral damage from resection (Fig. 4).

Intra-articular osteoid osteoma accounts for approximately 10% of all osteoid osteomas [5]. Diagnosis is challenging due to the rarity and non-specificity of its clinical presentation such as pain and it often gets confused with mono arthritis or even infectious etiology such as tuberculosis synovitis. Osteoid osteoma may be mistaken for other etiologies such as avascular necrosis of the femoral head, inflammatory arthritis, fatigue fracture, or even pigmented villonodular synovitis. Therefore, the mean delay between the onset of symptoms and diagnosis of intra-articular steroid osteoma varies from 1.5 to 3.5 years [6,7]. Due to the low efficacy of anti-inflammatory drugs in intra-articular osteoid osteoma, the effect of these drugs in the complete alleviating of symptoms does not constitute proof for the diagnosis [4]. Standard radiographs demonstrate a nidus in 85% of cases. When intra-capsular in location, radiographs only provide subtle findings because of a lack of sclerosis and periosteal reaction unlike in extra-articular locations [4]. MR imaging typically shows low intensity on T1 weighted with marrow edema. In our case, MRI did provide some clue for diagnosis which was later confirmed by CT scan. According to many authors, bone scans and CT scans are the investigation of choice for proper diagnosis [6,7,8]. Computed tomography remains the examination of choice when using high-resolution contiguous millimeter thin slices thus providing accurate data regarding the size and location of the lesion [9,10]. Initial treatment of osteoid osteoma involves the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug or aspirin. Surgical en bloc resection typically provides the adequate treatment. Other methods like CT-guided excision with a punch biopsy, percutaneous thermal ablation, and percutaneous radiofrequency thermal ablation are gaining popularity. Radiofrequency treatment reduced the average length of the stay in the hospital. A 94% success rate was recently shown in a case series by Woertler et al. [11]. Percutaneous techniques should be used in case of reliable diagnosis and easy access to the lesion with no associated iatrogenic risks. Otherwise, conventional surgery should be performed for efficient curative treatment with precise histopathological examination.

Osteoid osteoma is an important consideration in the differential diagnosis of unexplained musculoskeletal pain in a young patient. CT scan is the preferred imaging of choice. Radiofrequency ablation is a reasonable and minimally invasive method of treatment for intra-articular lesions when amendable.

Osteoid osteoma arising from unusual locations like intra-articular regions may be misleading and lead to delay in diagnosis and appropriate management. CT scan is the gold standard for diagnosis and radiofrequency ablation can be employed for lesions in difficult to access areas.

References

- 1.Frassica FJ, Waltrip RL, Sponseller PD, Ma LD, McCarthy EF. Clinicopathologic features and treatment of osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma in children and adolescents. Orthop Clin North Am 1996;27:559-74. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Jaffe HL. Osteoid-osteoma. Proc R Soc Med 1953;46:1007-12. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Lee EH, Shafi M, Hui JH. Osteoid osteoma: A current review. J Pediatr Orthop 2006;26:695-700. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Cassar-Pullicino VN, McCall IW, Wan S. Intra-articular osteoid osteoma. Clin Radiol 1992;45:153-60. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Franceschi F, Marinozzi A, Papalia R, Longo UG, Gualdi G, Denaro E. Intra-and juxta-articular osteoid osteoma: A diagnostic challenge: Misdiagnosis and successful treatment: A report of four cases. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2006;126:660-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Bauer TW, Zehr RJ, Belhobek GH, Marks KE. Juxta-articular osteoid osteoma. Am J Surg Pathol 1991;15:381-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Caillieret J, Fontaine C, Ducloux M, Letendart J, Duquennoy A. Osteoid osteoma of the upper extremity of the femur. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 1986;72Suppl 2:101-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Davies M, Cassar-Pullicino VN, Davies AM, McCall IW, Tyrrell PN. The diagnostic accuracy of MR imaging in osteoid osteoma. Skeletal Radiol 2002;31:559-69. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Allen SD, Saifuddin A. Imaging of intra-articular osteoid osteoma. Clin Radiol 2003;58:845-52. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Aisen AM, Glazer GM. Diagnosis of osteoid osteoma using computed tomography. J Comput Tomogr 1984;8:175-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Woertler K, Vestring T, Boettner F, Winkelmann W, Heindel W, Lindner N. Osteoid osteoma: CT-guided percutaneous radiofrequency ablation and follow-up in 47 patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2001;12:717-22. [Google Scholar | PubMed]