Tuberculosis should always be considered a differential diagnosis of a lytic lesion in endemic demography.

Dr. Furquan Ulhaque, Department Of Orthopaedics, Seth GS Medical College and KEM hospital, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: furquanulhaque@gmail.com

Introduction: Osteoarticular tuberculosis (OATB) contributes to around 10% of extrapulmonary tuberculosis of which the spine is the most common site. Isolated involvement of ulna diaphysis is extremely rare. We present a case of unifocal tuberculous osteomyelitis of ulna diaphysis in a 3 -year-old male child and highlight its resemblance with musculoskeletal tumors and stress the importance of GeneXpert mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB)/resistance to rifampicin (RIF) in the diagnosis of OATB.

Case Report: A mother of a 2-year-old male child incidentally noticed that her son complained of left forearm pain. She was not sure of any fall or trauma to the forearm. No history of fever or other constitutional symptoms was present. Clinical examination was uneventful except for local tenderness in over the dorsomedial aspect of the left mid forearm. A plain radiograph revealed an oval solitary lytic lesion over distal one-third ulna diaphysis. A needle biopsy was done after clinical, hematological, and radiological evaluation, and finally, GeneXpert detected tuberculosis without RIF. No further tests were required and the child was started on antitubercular therapy (ATT) which resulted in complete healing without any symptoms.

Conclusion: The authors conclude that it is therefore essential to consider tuberculosis in the differential diagnosis while evaluating a lytic bone lesion. Where possible, all patients should have a biopsy of the lesion and provide a specimen for GeneXpert MTB/RIF to confirm the diagnosis and drug susceptibility testing.

Keywords: Osteoarticular tuberculosis, ulna, diaphysis, child, lytic bone lesion, GeneXpert mycobacterium tuberculosis/resistance to rifampicin, ATT.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB) being endemic in India is known to involve any part of the human body [1]. The disease is common in adults and is found to be rare in the pediatric population [2]. Skeletal tuberculosis may behave differently in this age group compared with the adult population [3]. Isolated involvement of ulna diaphysis is extremely rare. Minimal initial symptoms, rarity of the lesion, and the ability to mimic more common pathologies account for the delay in diagnosis [4]. Lytic bone lesions in children can represent benign, malignant, or infectious processes and require a broad differential diagnosis and meticulous approach of clinical, radiological and hematological evaluation for accurate diagnosis and treatment [5,6]. We present a case of unifocal tuberculous osteomyelitis of ulna diaphysis in a 2 -year-old child and highlight its resemblance with musculoskeletal tumors and stress the importance of GeneXpert MTB/resistance to rifampicin (RIF) in the diagnosis of osteoarticular tuberculosis (OATB). When investigating the cause of lytic bone lesions, the authors urge to consider tuberculosis (TB) as a differential diagnosis even in the absence of pulmonary symptoms or risk factors of TB infection.

A mother of a 2- year-old male child brought her son to our outpatient department when she noticed her son complained of left forearm pain when she had to hold his forearm while changing his clothes. She was not sure of any fall or trauma to the forearm. No history of fever or other constitutional symptoms was present. On examination, there were no swelling, deformity, or skin color changes. No scars or sinuses. Palpation revealed tenderness over the dorsomedial aspect of the left mid forearm without any palpable defect, or any change in the bony consistency of the ulna over the area, and the skin was non-adherent. The wrist and elbow range of movement were full and painless. There was no lymphadenopathy. A plain radiograph revealed an oval solitary lytic lesion over distal one-third ulna diaphysis with the permeative pattern of bone destruction and narrow zone of transition. The lesion was expansile with cortical thickening and solid periosteal reaction without cortical breach or soft-tissue extension (Fig. 1).  On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), patchy altered marrow signal intensity in the form of T1 hypointense, showing mild heterogeneous post-contrast enhancement in the distal one-third ulnar diaphysis, with associated mild cortical thickening and thick linear sclerotic periosteal reaction (Fig. 2).

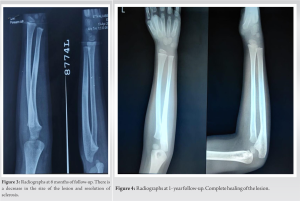

On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), patchy altered marrow signal intensity in the form of T1 hypointense, showing mild heterogeneous post-contrast enhancement in the distal one-third ulnar diaphysis, with associated mild cortical thickening and thick linear sclerotic periosteal reaction (Fig. 2). Basic hematological workup such as complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) was within normal parameters. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was performed under fluoroscopic guidance and the specimen obtained was <1cc of hemorrhagic fluid which was sent for bacterial culture sensitivity, cytological examination, and GeneXpert MTB/RIF. The GeneXpert detected tuberculosis without RIF and eventually cultures for bacteria yielded no growth and cytological examination was inconclusive. No further tests were required and the child was started on antitubercular therapy (ATT) which included four drugs (isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol) for 2 months, followed by three drugs (isoniazid, rifampicin, and ethambutol) for 7 months. The dose of these drugs was based on the weight of the child. Emphasis was laid on optimal nutrition in the form of a high protein diet and was assessed by gain in weight, every month. A Radiograph of the forearm at 6- month follow-up revealed a decrease in the size of the lesion and resolution of sclerosis (Fig. 3). A Radiograph at 1- year follow-up showed complete healing without any symptoms (Fig. 4).

Basic hematological workup such as complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) was within normal parameters. Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) was performed under fluoroscopic guidance and the specimen obtained was <1cc of hemorrhagic fluid which was sent for bacterial culture sensitivity, cytological examination, and GeneXpert MTB/RIF. The GeneXpert detected tuberculosis without RIF and eventually cultures for bacteria yielded no growth and cytological examination was inconclusive. No further tests were required and the child was started on antitubercular therapy (ATT) which included four drugs (isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol) for 2 months, followed by three drugs (isoniazid, rifampicin, and ethambutol) for 7 months. The dose of these drugs was based on the weight of the child. Emphasis was laid on optimal nutrition in the form of a high protein diet and was assessed by gain in weight, every month. A Radiograph of the forearm at 6- month follow-up revealed a decrease in the size of the lesion and resolution of sclerosis (Fig. 3). A Radiograph at 1- year follow-up showed complete healing without any symptoms (Fig. 4).

OATB contributes to around 10% of EPTB of which the spine is the most common site, amounting to around half of skeletal EPTB followed by the hip and knee [7]. However, any bone can be affected. Sometimes TB presents at unusual sites where it often becomes difficult to reach a specific diagnosis [8]. Due to the distribution of reticuloendothelial and hemopoietic tissue, children tend to have a more peripheral manifestation of the disease [9]. Among risk factors for OATB, poor socioeconomic conditions constitute a major risk factor [10]. Injuries may be capable of reactivating pre-existing tuberculous foci. The tubercle bacilli can reach the bone and joints by hematogenous spread from a pulmonary lesion or by contiguous spread from a focus of osteomyelitis [11]. OATB is a source of functional disability that should be recognized and treated early, particularly in children, given that appropriate management can lead to a full recovery [12]. OATB of the limbs in children is an insidious condition and is often associated with diagnostic delay and a risk of severe residual disability [13]. Non-specific pain and swelling are the most common presenting symptoms of OATB. Chronic monoarthritis of insidious onset is the most typical presentation [14]. Pain, functional disability, evening rise of temperature, and nocturnal sweats have been described consistently. The diagnosis is based on a set of converging clinical, laboratory results, and radiological arguments. TB of ulna diaphysis in the pediatric population is extremely rare. Thus, a high index of suspicion is necessary to make the diagnosis in children who present with painful or painless swelling or cold abscess. In the absence of these typical findings and rare site of presentation, diagnosis may be delayed. TB is known to mimic the symptoms of many other diseases, including various cancers and other infections [5,13]. TB of bone is a rare but important cause of lytic bone lesions and can be easily missed, potentially resulting in ineffective or potentially harmful treatments [6,15]. Benign causes of lytic bone lesion include fibrous lesions like non-ossifying fibroma and fibrous cortical defect, bone-forming tumors such as osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma, cystic lesions such as unicameral bone cyst and aneurysmal bone cyst, and benign aggressive tumors such as chondromyxoid fibroma, chondroblastoma, giant cell tumor, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Malignant causes include the primary pediatric bone cancers such as osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma, lymphoma and metastatic lesions from undiagnosed solid tumors of unknown primary elsewhere in the body, and rarely multiple myeloma in children or adolescents. Lytic bone lesions due to bacterial infections are most commonly due to Gram-positive organisms causing osteomyelitis, although Gram-negative, anerobic, or atypical organisms can also be the causative agents. Therefore, the management of these various conditions differs widely hence highlighting the importance of the meticulous approach to arrive at an accurate and timely diagnosis. The initial workup in children with painful lesions of bone should include a thorough history, physical examination, and plain radiographs. Often, patient’s age and plain radiographs are sufficient to arrive at a specific diagnosis. Radiographs are cheap, easily available and help in better characterization in the evaluation of focal bony lesions. If indicated, computed tomography scans may provide better imaging of the bones themselves and evaluate the cortex and matrix of the lesion, and MRI scans delineate soft-tissue structures and are the best modality to define extent of lesion whether intramedullary and/or extraosseous disease and the relationship to the neurovascular structures. MRI, however, is not useful to differentiate benign from malignant lesions. Bone scan which is used to determine the activity of a lesion may identify additional areas of disease such as multiple lesions or skeletal metastasis that were not noted earlier in the chief complaint. Hematology should include a complete blood count with differential, CRP, and ESR which may help identify infectious processes. Biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosing bone lesions. A biopsy is to be done only after the clinical, radiological, and hematological evaluation is complete [16]. A biopsy can be FNAC, core needle, incisional, or excisional. In a country like India, where TB is endemic molecular tests like GeneXpert MTB/RIF identify genetic makeup of live/dead bacteria and do not require mycobacterial growth, hence substantially reducing time for diagnosis [17]. The test is based on nucleic acid amplification of MTB bacilli using polymerase chain reaction followed by its detection using certain markers in genetic material. The added advantage is they also determine rifampicin resistance. A single assay run can provide both detection of TB and detection of rifampicin resistance within 2 h. Conventional laboratory techniques like direct microscopy are far from being sensitive and cultures are time-consuming, require biosafety measures, and need trained laboratory personnel, and therefore, GeneXpert MTB/RIF is recommended by the World Health Organization [18]. Uncomplicated TB is a medical disease [7]. The main treatment for OATB is multidrug ATT based on the body weight of the patient [8,12]. Compliance must be ensured. Analgesics, rest, immobilization, splinting, and braces may be necessary in the early stages of the disease and once the inflammation and pain have subsided, patients should be encouraged to start joint range of motion exercises. Tubercular osteomyelitis, if advanced may require protection to prevent pathological fractures. Nutrition should be optimized [19].

TB is endemic in India and OATB can have a varied presentation in children. It is therefore essential to consider it in the differential diagnosis while evaluating a lytic bone lesion. Where possible, all patients should have a biopsy of the lesion and provide a specimen for GeneXpert MTB/RIF to confirm the diagnosis and drug susceptibility testing. The main treatment for pediatric OATB is non-operative and complete resolution is possible with multidrug antitubercular chemotherapy.

In India, always consider TB in the differential diagnosis in the workup of a lytic bone lesion. Whenever possible, specimen should be made available for GeneXpert MTB/RIF for early and reliable diagnosis of TB. Surgical treatment of bone lesions has markedly reduced with the introduction of effective antitubercular chemotherapy. When diagnosed early and started on ATT and supplemented with a high protein diet, OATB in children shows complete clinical and radiological resolution of the disease.

References

- 1.Powell DA, Hunt WG. Tuberculosis in children: An update. Adv Pediatr 2006;53:279-322. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Maltezou HC, Spyridis P, Kafetzis DA. Extra-pulmonary tuberculosis in children. Arch Dis Child 2000;83:342-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Rasool MN. Osseous manifestations of tuberculosis in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2001;21:749-55. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Prakash J, Mehtani A. Hand and wrist tuberculosis in paediatric patients - our experience in 44 patients. J Pediatr Orthop B 2017;26:250-60. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Lemme SD, Kevin Raymond A, Cannon CP, Normand AN, Smith KC, Hughes DP. Primary tuberculosis of bone mimicking a lytic bone tumor. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2007;29:198-202. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Gyawali B, Sharma BD, Kayastha N, Joshi A. Tuberculosis mimicking bone tumor. Med J Shree Birendra Hosp 2012;11:49-51. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Rajasekaran S, Soundararajan DC, Shetty AP, Kanna RM. Spinal tuberculosis: Current concepts. Global Spine J 2018;8:96S-108. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Agarwal A. Paediatric osteoarticular tuberculosis: A review. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2020;11:202-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Dhammi IK, Jain AK, Singh S, Aggarwal A, Kumar S. Multifocal skeletal tuberculosis in children: A retrospective study of 18 cases. Scand J Infect Dis 2003;35:797-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Nelson LJ, Wells CD. Global epidemiology of childhood tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2004;8:636-47. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Davidson PT, Horowitz I. Skeletal tuberculosis. A review with patient presentations and discussion. Am J Med 1970;48:77-84. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Teklali Y, El Alami ZF, El Madhi T, Gourinda H, Miri A. Peripheral osteoarticular tuberculosis in children: 106 case-reports. Joint Bone Spine 2003;70:282-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Malik S, Joshi S, Tank JS. Cystic bone tuberculosis in children--a case series. Indian J Tuberc 2009;56:220-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Cruz AT, Starke JR. Clinical manifestations of tuberculosis in children. Paediatr Respir Rev 2007;8:107-17. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Wiratnaya IG, Susila IW, Sindhughosa DA. Tuberculous osteomyelitis mimicking a lytic bone tumor: Report of two cases and literature review. Rev Bras Ortop (Sao Paulo) 2019;54:731-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Bickels J, Jelinek JS, Shmookler BM, Neff RS, Malawer MM. Biopsy of musculoskeletal tumors. Current concepts. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999;368:212-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Abhimanyu S, Jain AK, Myneedu VP, Arora VK, Chadha M, Sarin R. The role of cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification test (CBNAAT), line probe assay (LPA), liquid culture, acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smear and histopathology in the diagnosis of osteoarticular tuberculosis. Indian J Orthop 2021;55:157-66. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Singh D, Meena AK, Vahora N, Kumar R, Khanna G, Nair D, et al. CB-NAAT MTB/RIF assay and histopathology correlation in diagnosis of osteoarticular tuberculosis using culture as reference standard. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2019;10:S53-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Wilbur AK, Farnbach AW, Knudson KJ, Buikstra JE. Diet, tuberculosis, and the paleopathological record. Curr Anthropol 2008;49:963-77. [Google Scholar | PubMed]