Determining the incidence of accessory navicular bone in the Indian population aids in understanding its prevalence, clinical significance, and potential implications for diagnosis and treatment strategies while dealing with foot pain.

Dr. Raj Pawar, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College, Hospital and Research Centre, Dr. D. Y. Patil University, Pune, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: rajvinaypawar@gmail.com

Introduction: The purpose of this study was to assess the incidence of accessory navicular bone (ANB) among the Indian population.

Materials and Methods: This study consisted of 510 cases of which 1020 plain radiographs of both feet were taken (anteroposterior and lateral/oblique) belonging to the age group of 18 years and older of both genders. This study was conducted retrospectively from July 2023 to July 2024 in the Department of Orthopaedics and Radiology at a Tertiary level institute. Ethics approval number I.E.S.C./W/219/2024. The primary outcome to measure was the incidence of ANB in patients consulting the orthopedic outpatient department, and the secondary outcome measured the classification of ANB into its various subtypes and the total percentage of symptomatic ANB cases.

Results: Out of the 1020 X-rays assessed (510 cases) and evaluated it was found that 125 cases showcased signs of ANB in them, which amounts to 24.5% of cases. The classification of ANB according to their subtypes showed that Type 2a-b and Type 1-a were the most prevalent 23 (18.4%) and 23 (18.4%), respectively. Out of the total 125 ANB cases, only 13 were symptomatic, whereas the remaining cases were asymptomatic.

Conclusion: In conclusion, the incidence of ANB in the Indian population was 24.5%, wherein the symptomatic incidence was 10.4%. Keeping this in mind, it is imperative to consider ANB as a differential diagnosis when treating medial-side foot pain. To our knowledge, this is the first paper of its kind that brings to light the incidence of ANB in clinical practice among the Indian population.

Keywords: Accessory navicular bone, foot pain, incidence, foot anomalies.

Accessory ossicles result from incomplete fusion of the secondary ossification center to the main bone. The majority of the ossicles are asymptomatic and usually detected incidentally in radiographic studies. Pain can arise from fractures, dislocations, degenerative changes, osteoarthritis, osteochondral lesions, avascular necrosis, tumors, or irritation and impingement of nearby soft tissues. They are detected at various joints such as the shoulder, elbow, wrist, hip, knee, or ankle, but the foot and ankle are some of the most common locations with 24 different types [1]. The accessory navicular bone (ANB) is the most common accessory ossicle seen in the foot and ankle. It is also known as os naviculare, tibiale externum, pre-hallux, os supranavicular, talonaviculare ossicle, navicular secundum, accessory scaphoid, accessory tarsal scaphoid, divided navicular, and Pirie’s bone. The incidence of ANB in the foot varies between 4% and 21% among the general population [2-5]. Coughlin et al. classified ANB into three types [6]. Type I is a small round or oval-shaped accessory ossicle embedded in the posterior tibialis tendon and is usually asymptomatic. Type II is a triangular-shaped accessory ossicle attached to navicular tuberosity by a thin layer of fibrocartilage and is usually symptomatic, and misdiagnosed as a navicular fracture. Sella and Lawson [7] further differentiated Type II into two subtypes: Type IIA is attached to the navicular tuberosity by a less acute angle and Type IIB is located inferiorly to the navicular tuberosity. Type III is fused with the navicular tuberosity, producing cornuate-shaped bone. The ANB is usually asymptomatic and is incidentally detected on the radiographs; however, few can be painful due to local mechanical factors such as tension, shearing, or compression forces resulting from twisting injuries or overuse [8]. Among the patients with ANB, the Type II ANB is usually painful. The differential for symptomatic ANB is avulsion fractures of the tuberosity, tarsal stress fractures, arthritis, posterior tibial tendon rupture, and insufficiency. Certain foot pathologies, such as flatfoot and posterior tibial tendon insufficiency, are associated with ANB, which are symptomatic. The symptomatic ANB can be managed conservatively or may need surgical intervention, which has been discussed by [9], who found success in the management of symptomatic cases by Kidner and modified Kidner procedures and [10] also reached a similar conclusion with regards to surgical management of symptomatic ANB cases; however, a definitive guideline for the ANB management is lacking in the literature [11-13]. There are few studies assessing the prevalence of symptomatic and asymptomatic ANB, and no such study is being done in the Indian Population. Accurate diagnosis of the ANB can decrease the rate of misdiagnosis and unnecessary orthopedic intervention in the emergency department in patients with twisting injuries of the foot. Furthermore, appropriate management of the symptomatic ANB can be done if it is timely diagnosed and staged. This study aims to determine the prevalence and pattern of the ANB in the Indian population. Furthermore, to classify the ANB as per the Coughlin classification and assess its relation with age and sex.

The medical records of patients who underwent standard anteroposterior and oblique/lateral radiographs of both feet aged 18 years and above of both genders were included. The study was done retrospectively from July 2023 to July 2024 in the Department of Orthopaedics and Radiology at a Tertiary level institute. Approval for the research was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College, Hospital and Research Centre, Pimpri, with the ethics approval number I.E.S.C./W/219/2024. Patients with previous surgery for the foot, past history of traumatic injury to the foot, skeletally immature individuals, diagnosed cases of rheumatoid diseases, and incomplete documented cases were excluded from the study. The sample size was decided by the following formula n = N × (x+N-1) with a 95% confidence interval and a 5% margin of error and found to be 510 cases, of which 1020 X-rays were taken. A proportion of 11% was estimated based on a similar study of 650 patients at Akdeniz University Hospital [14]. The radiographs of the included patients were reviewed by two independent observers for the presence/absence of ANB. One of the observers is an expert in foot and ankle surgery and the other is a Professor of the orthopedics department. In cases of disagreement, a third observer specialist of foot and ankle was consulted. The primary outcome to measure was the Incidence of ANB in patients consulting the orthopedic outpatient department, secondary outcome measured the classification of ANB into its various subtypes and the total percentage of symptomatic ANB cases. The data of the analyzed radiographs was maintained in a data collection sheet according to their relevant demographics and clinical presentation. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS software v.27, statistical significance was set at <0.05. Differences between groups were assessed using the Chi-squared test for categorical data and analysis of variance for continuous variables.

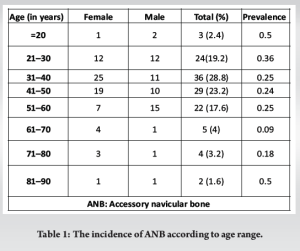

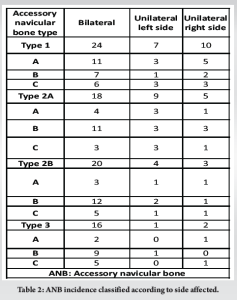

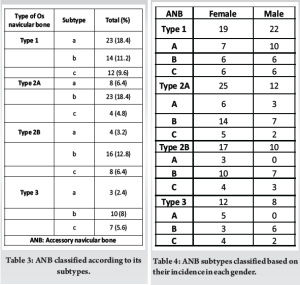

Out of the 1020 X-rays assessed (510 cases) and evaluated it was found that 125 cases showcased signs of ANB in them, which amounts to 24.5% of cases. Within the 125 cases, it was seen that the prevalence was higher in females (n = 72, 57.6%) than in males (n = 53, 43.4%) (Z = 2.39, P = 0.017). Patients aged between 31 and 40 years exhibited the maximum number of cases – 36 (28.8%) followed by the age group of 41–50 which showed 29 cases (23.2%) (Table 1). The incidence of ANB varied by the affected side, with the majority of cases demonstrating bilateral involvement. Where 24 (19.2%), 38 (30.4%), and 16 (12.8%) of the total cases were bilateral for Type 1, Type 2 (A and B), and Type 3, respectively. The unilateral left side was seen in 7, 13, and 1 of total cases for Type 1, Type 2 (A and B), and TYPE 3, respectively, and similarly, the unilateral right side showed 10, 8, and 2 of total cases for Type 1, Type 2 (A and B), and Type 3, respectively (Table 2). The classification of ANB according to their subtypes showed that Type 2A-b and Type 1-a were the most prevalent 23 (18.4%) and 23 (18.4%), respectively, followed by Type 2B-b which was 16 (12.8%) of the total cases (Table 3). The classification of ANB according to subtypes in males and females revealed that Type2a-b was the most common subtype among females, consisting of 14 cases, whereas Type1-a was the most common subtype among men, which consisted of 10 cases (Table 4). In addition, it was found that only 13 cases of the total ANB cases were symptomatic (Type 2 – 9 cases, Type 3 – 3 cases, and Type 1 – 1 case) out of the 125 total cases and rest were asymptomatic.

The incidence of ANB is noted to be between the range of 2% and 25% among the general population [8,15,16]. In our study, 24.5% of the 1,020 X-rays screened (510 cases) showed ANB, corresponding to 125 patients. The prevalence of ANB was commonly seen in females (n = 72, 57.6%) compared to males, in similar studies conducted, it was seen that a prevalence of 55.6% was recorded by [14] and 67.5% in a study by [16]. This study also identified the most commonly affected age group for ANB as 31–40 years, followed by 41–50 years, with females being predominantly affected. This contrasts with the findings of a study by [15], which reported the most affected age group as 51–60 years. The aforementioned study was conducted in a Chinese population, and the discrepancy raises the question of whether ethnicity may influence the incidence of ANB, warranting further investigation. In this study, the majority of ANB cases (%) involved bilateral presentation, with 24 cases classified as Type 1, 38 as Type 2, and 16 as Type 3. Type 2 accounted for the largest proportion of cases, which aligns with the findings of [15], where Type 2 made up 36.8% of cases. However, in a study by [5], Type 3 ANB was the most common, comprising 32% of all cases. This study described all types of ANB based on Coughlin’s classification, with Type 1 and Type 2A-b being the most prevalent, each accounting for 23 cases (18.4%). In contrast, similar studies by [15,16] reported a higher prevalence of Type 1 ANB, at 41.2% and 41.6%, respectively. This notable difference in prevalence raises interesting questions about the factors contributing to the variation between populations. It suggests the possibility of underlying demographic, genetic, or environmental influences that may affect the distribution of ANB types, warranting further investigation to understand these discrepancies more thoroughly. In this study, the overall incidence of symptomatic ANB was 13 cases (10.4%), where the symptoms were attributed solely to ANB, and the most common type causing this was Type 2, with no other underlying etiological factors mimicking foot pain. In contrast, a study by [16] reported four symptomatic cases (3.4%) out of 117, but the type involved has not been described, whereas a study conducted in a Turkish population by [14] found a comparable incidence of 11.7% to our study where the commonest type involved was Type 2 and in a study by [15] the incidence of symptomatic ANB cases was 20.2% which was found to be higher compared to our study and the most common type involved being Type 2, this is owed to the fact there was only inclusion of symptomatic cases of foot pain in their study which has influenced their high incidence of symptomatic ANB cases. The occurrence of symptomatic ANB appears to be influenced by daily activities, with a progressive increase in symptoms seen in individuals engaged in high-demand activities involving the foot and ankle [17]. The clinical relevance of this study lies in distinguishing symptomatic ANB from other pathologies often included in differential diagnoses, such as navicular tuberosity avulsion, tarsal stress fractures, arthritis, flatfoot, or posterior tibial tendon insufficiency. Proper differentiation between ANB and navicular or tarsal fractures requires physicians to understand the natural progression of ANB, as symptomatic ANB frequently appears in young athletes, typically presenting with symptoms during physical activities such as walking or exercising, which can impact their performance. ANB may present in childhood or early adulthood. To our knowledge, this is the first study describing the incidence and anatomic variation of symptomatic and asymptomatic ANB in the Indian population. This study was conducted at a tertiary care center, involving patients from diverse regions and ethnic backgrounds. Understanding the incidence of ANB, its common types, and the populations at risk of developing symptomatic ANB is crucial for early diagnosis, differentiation from navicular fractures, and foot arthritis, and the development of an appropriate management plan. Our study was a retrospective observational, and the morphology of ANB was assessed on plain radiographs, but the use of computed tomography could have aided in a better understanding of the morphology of ANB cases.

The incidence of ANB in the Indian population was 24.5%, whereas the symptomatic incidence was 10.4%. The documented incidence of ANB is comparatively less than the incidence in Chinese and Malaysian populations. Type 1a and Type 2a-b were the most prevalent subtypes in our study in contrast to the previously reported subtypes of other studies. The prevalence of ANB was commonly seen in females in our study along with the most commonly affected age group being 31–40 years. Keeping this in mind, it is imperative to consider ANB as a differential diagnosis when treating medial-side foot pain which may be missed or inadequately treated in our day-to-day clinical practice.

Assessing the incidence of ANB highlights its clinical relevance for early diagnosis and provides appropriate management for the same in our daily clinical practice.

References

- 1.Keles-Celik N, Kose O, Sekerci R, Aytac G, Turan A, Güler F. Accessory ossicles of the foot and ankle: Disorders and a review of the literature. Cureus 2017;9:e1881. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Lawson JP. International skeletal society lecture in Honor of Howard D. Dorfman. Clinically significant radiologic anatomic variants of the skeleton. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1994;163:249-55. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Nakayama S, Sugimoto K, Takakura Y, Tanaka Y, Kasanami R. Percutaneous drilling of symptomatic accessory navicular in young athletes. Am J Sports Med 2005;33:531-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Stolarz K, Osiowski A, Preinl M, Osiowski M, Jasiewicz B, Taterra D. The prevalence and anatomy of accessory navicular bone: A meta-analysis. Surg Radiol Anat 2024;46:1731-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Kalbouneh H, Alajoulin O, Alsalem M, Humoud N, Shawaqfeh J, Alkhoujah M, et al. Incidence and anatomical variations of accessory navicular bone in patients with foot pain: A retrospective radiographic analysis. Clin Anat 2017;30:436-44. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Mann RA, Saltzman CL. In: Coughlin MJ, editor. Surgery of the Foot and Ankle. St. Louis: Mosby; 1999. p. 745-58. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Sella EJ, Lawson JP. Biomechanics of the accessory navicular synchondrosis. Foot Ankle 1987;8:156-63. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Campbell JT, Jeng CL. Painful accessory navicular and spring ligament injuries in athletes. Clin Sports Med 2020;39:859-76. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Randall GW, Butler JJ, Fur RL, Konar K, Rampersad C, Azam MT, et al. Outcomes following surgical treatment for symptomatic accessory navicular: A systematic review. Foot Ankle Orthop 2023;8:2473011423S00371. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Wariach S, Karim K, Sarraj M, Gaber K, Singh A, Kishta W. Assessing the outcomes associated with accessory navicular bone surgery-a systematic review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2022;15:377-84. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Choi YS, Lee KT, Kang HS, Kim EK. MR imaging findings of painful type II accessory navicular bone: Correlation with surgical and pathologic studies. Korean J Radiol 2004;5:274. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Fredrick LA, Beall DP, Ly JQ, Fish JR. The symptomatic accessory navicular bone: A report and discussion of the clinical presentation. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2005;34:47-50. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Kiter E, Günal İ, Turgut A, Köse N. Evaluation of simple excision in the treatment of symptomatic accessory navicular associated with flat feet. Orthop Sci 2000;5:333-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Keles Coskun N, Arican RY, Utuk A, Ozcanli H, Sindel T. The incidence of accessory navicular bone types in Turkish subjects. Surg Radiol Anat 2009;31:675-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Huang J, Zhang Y, Ma X, Wang X, Zhang C, Chen L. Accessory navicular bone incidence in Chinese patients: A retrospective analysis of X-rays following trauma or progressive pain onset. Surg Radiol Anat 2014;36:167-72. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Alsager GA, Alzahrani K, Alshayhan F, Alotaibi RA, Murrad K, Arafah O. Prevalence and classification of accessory navicular bone: A medical record review. Ann Saudi Med 2022;42:327-33. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Mygind HB. The accessory tarsal seaphoid: Clinical features and treatment. Acta Orthop Scand 1953;23:142-51. [Google Scholar | PubMed]