Salter–Harris IV injury of distal tibial physis along with sagittal plane talar body fracture may be an occult combination in physeal injuries of children and requires high index of suspicion for diagnosis to avoid missing the injury.

Dr. Nishant Bhatia, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Maulana Azad Medical College and Associated Lok Nayak Hospital, New Delhi, India. E-mail: bhatianishant1111@gmail.com

Introduction: Distal tibial physeal fractures and talus fractures are rare injuries in children and adolescents. Even rare is a combination of these two fractures. Axial compression is an accepted mechanism of injury in talus fractures with position of foot at the point of impact determining the extended patterns. A concomitant medial malleolus fracture suggests a supinated foot at the time of impact.

Case Presentation:We report a case of a 13-year-old girl child who sustained a Type IV Salter–Harris injury of distal tibial physis along with a displaced vertical (sagittal) type fracture of the talus body. The uniqueness in our case was that the talar body fracture was a vertical type and that too displaced in the same line along with medial malleolus fragment. Open reduction of both the fractures was done through anteromedial approach followed by minimal fixation with K-wires. Good results were observed at 1 year following the surgery.

Conclusion: Injuries of this nature are very uncommon and even more unusual in pediatric age group. This case report emphasizes the importance of having a high suspicion of uncommon fracture patterns in pediatric age group. Early and prompt diagnosis should be made using CT/MRI as a lot of these injuries may go unnoticed on plain radiographs.

Keywords: Distal tibial physeal injury, Salter–Harris IV, Sagittal fracture of talus, talar body fracture, vertical fracture.

Distal tibial physeal fractures account for about 25–35% of all physeal injuries [1, 2]. Talus fractures are extremely rare in children and adolescents and account for only about 0.008% of pediatric fractures [3, 4]. The most common site to be involved in a talus fracture is neck-body junction; however, talar body fractures are also infrequently reported. In adults, about 16%–19% of talar neck fractures can be associated with a medial malleolus fracture [5]; however, the pediatric counterpart of such an injury pattern (involving distal tibial physis and talar neck) is extremely rare. Even rarer is a vertical fracture of talar body occurring along with distal tibial physeal injury with very few cases reported in the literature till date [6, 7]. Axial compression is an accepted mechanism of injury in such fractures with position of foot at the point of injury determining the extended patterns. A concomitant medial malleolus fracture suggests a supinated foot at the time of impact. A prompt diagnosis and early treatment are needed in such cases so as to prevent the complications of malunion, deformity, avascular necrosis, and secondary osteoarthritis [4, 8].

We report a unique case of a 13-year-old girl child who sustained a Type IV Salter–Harris injury of distal tibial physis along with a displaced vertical (sagittal) type fracture of the talus body. The uniqueness of the fracture pattern in our case was that the talar fracture was in sagittal plane and appeared to have occurred in the same line of direction as the medial malleolus fracture. Open reduction of both the fractures was done through anteromedial approach. Fixation was accomplished with K-wires following which immobilization was done in a plaster cast. We observed good results following surgery. The main aim of this report is to highlight this rare and unique injury pattern and to emphasize the fact that children often have unusual fracture patterns that need a thorough evaluation with advanced imaging by CT/MRI. Meticulous reduction and minimal fixation preserve the blood supply in this notorious area and grant good functional outcome.

In 2019, a 13-year-old girl was brought to our orthopedic emergency following a road traffic accident. She was hit by a car following which she fell into a ditch and sustained injuries to her right ankle. On examination, she had swelling, tenderness, and ecchymosis on the dorsal and medial aspect of right ankle with no neurovascular problems. She was unable to bear weight and her ankle range of motion was painfully restricted.

Radiographs of right ankle and foot showed a displaced distal tibial physeal injury of medial malleolus with fracture line passing through epiphysis with a metaphyseal fragment (Salter–Harris Type IV) (Fig. 1). We could make out a step in the outline of the talar dome which raised a suspicion, and a CT scan was ordered to better delineate the injury.

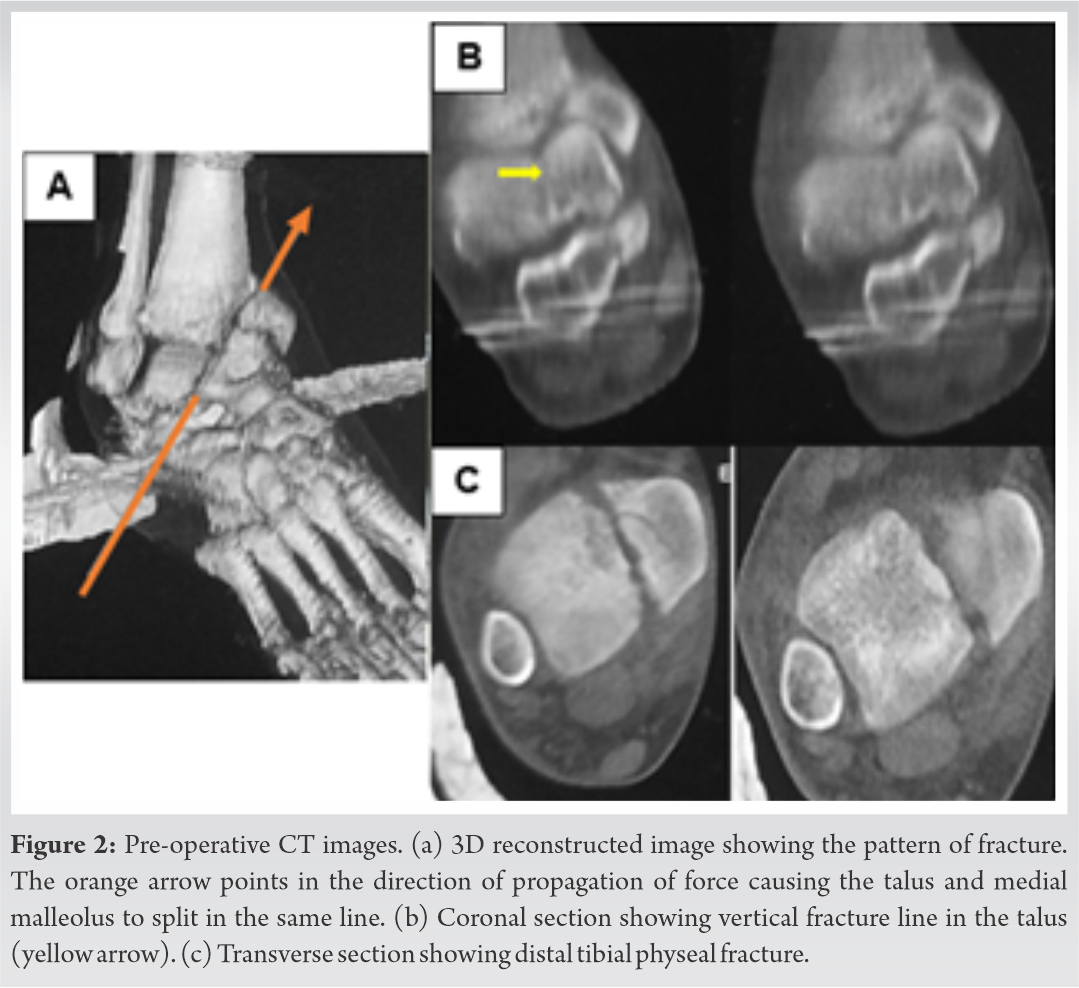

The CT scan demonstrated an oblique fracture line splitting the talar body into medial and lateral fragments with the fracture line passing from proximal medial to distal lateral direction. This fracture line was in line with the fracture of the distal tibia physis (Fig. 2).

The patient was planned for open reduction and internal fixation as there was significant depression (5 mm) in the talar dome. Under general anesthesia and caudal block, in supine position with tourniquet control, a 6 cm long longitudinal incision was given just medial to tibialis anterior (TA) tendon, centered over the ankle joint. The extensor retinaculum was incised, and TA tendon retracted laterally. The joint capsule was incised in line with the skin incision exposing the distal tibial epiphysis and body of talus.

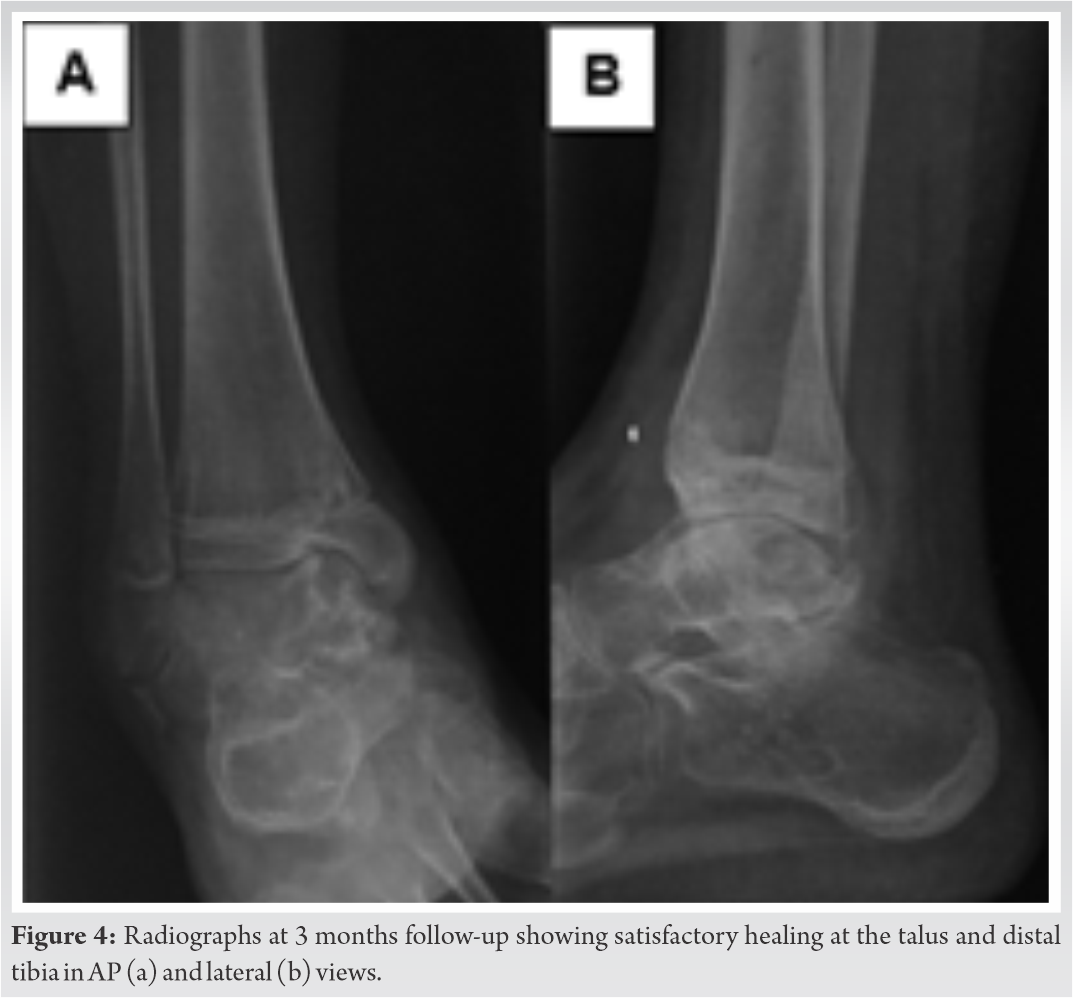

The talus fracture was reduced using Kirschner wires (K-wires) as joy sticks and fixed with three 1.6 mm K-wires. Two K-wires were passed parallel to the joint surface and a third K-wire was passed from proximal medial to distal lateral direction thus obtaining a “cross” configuration. The medial malleolus fragment was then reduced to distal tibia and fixed with two K-wires from medial to lateral direction in an “all epiphyseal” manner so as to avoid damage to the physis. The metaphyseal fragment was small and not deemed suitable for fixation (Fig. 3).

The stability of fixation was confirmed under vision by moving the ankle joint. Layered closure was done followed by immobilization of ankle in neutral position in a below knee plaster slab. The post-operative period was uneventful. Suture removal was done at 2 weeks and range of motion started at 6 weeks. The wires from tibia were removed at 6 weeks, while the talus wires were removed at 8 weeks.

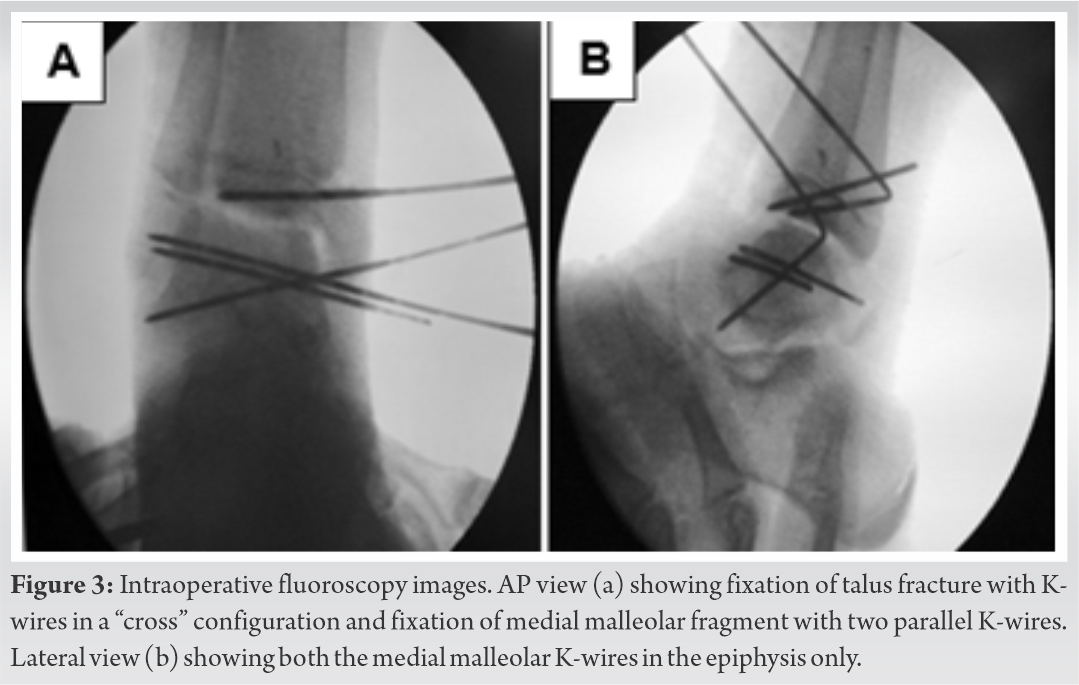

Satisfactory radiological healing was seen at 3 months (Fig. 4) and protected weight-bearing was started. Weight-bearing was gradually progressed, and the patient went on to have a good functional recovery.

At 1 year follow-up, the distal tibial and fibular physes were seen to be near closure. A varus of 5° at distal tibia along with a minimal step in talar dome (Fig. 5a) was noted but accepted without resorting to any further intervention, as the patient had no functional limitation. The patient was ambulating full weight-bearing without pain. She could squat with the heel off the ground. The range of motion was 20° of dorsiflexion (10° less as compared to opposite side) and 45° of plantar flexion (comparable to opposite side) (Fig. 5b, 5c).

Talus fractures constitute around 5% of all foot injuries and body fractures comprise 1% of all talus fractures [9]. In children, the combination of fractures seen in this case (Marti Type III talus fracture and Salter–Harris IV distal tibial physeal injury) are even less common [10]. To the best of our knowledge, only two cases with an injury pattern similar to our case (in children) have been reported in the literature [6, 7].

In the pediatric age group, ankle injuries often leave the ligaments intact and cause bony injuries that are mostly in the form of bruises, hence, easily missed on plain radiographs. In a study by Launay et al., 6% of all the pediatric ankle fractures were seen only on MRI and most of these involved the lateral ankle [11]. Moreover, an MRI study by Endele et al. demonstrated that all their patients of acute ankle injuries had bone bruises and only 10% of them involved fractures [12]. Our case study, therefore, reports a very rare combination of medial malleolus fracture with a displaced vertical type fracture of talar body.

The mechanism of injury thought to be involved in the present case was axial compression in a supinated foot. The axial force, transmitting in an oblique direction from distal-lateral to proximomedial aspect of ankle, caused the talar body to split into a lateral fragment and a medial fragment. As the force propagated further across the joint, it fractured the distal tibial epiphysis, physis, and metaphysis in the very same line as talus, thus leading to a Type IV Salter–Harris injury. As the foot was in a supinated position (plantar flexed and inverted), continued axial compression caused the medial talar fragment along with the medial malleolus to displace proximally, whereas the lateral fragment, along with the intact lateral malleolus and the lateral part of the distal tibia, stayed in its place (Fig. 2).

Crosswell et al. managed a similar case conservatively in a plaster cast as both the talus and medial malleolus fractures in their report were undisplaced [7]. The talus fracture in their report was a compression fracture of medial talar cortex (of body) with a horizontal fracture line. Kothadia et al. managed the malleolar component in their case study by closed reduction under fluoroscopy followed by fixation with cancellous screws [6]. This was followed by an arthroscopy assisted reduction and percutaneous cancellous screw fixation of the talus fracture which was a depression type injury of medial talar dome [6]. The uniqueness in our case was that the talar fracture was a vertical split fracture (in sagittal plane) that seemed to be in a continuous line as the medial malleolus fracture. Moreover, both the medial malleolus and medial talar fragment were displaced proximally in the same line. We were not able to find any cases reported with such a pattern of talus fracture along with medial malleolus fracture in children.

We chose to perform minimal fixation using K-wires only so as to limit the iatrogenic damage to the blood supply in the notorious talar region. A close monitoring of the patient is always needed in such injuries as re-displacement, avascular necrosis, and non-union which are not uncommon [8]. In our case, both the fractures showed radiological healing by 3 months and the patient had a good functional outcome. A mild varus of 5° and a minimal step in talar dome were noted at the last follow-up, but since the patient had no complaints of functional limitation or limb length discrepancy; further, intervention was not deemed necessary.

Injuries of this nature are very uncommon and even more unusual in pediatric age group. This case report emphasizes the importance of having a high suspicion of uncommon fracture patterns in pediatric age group. Early and prompt diagnosis should be made using CT/MRI as a lot of these injuries may go unnoticed on plain radiographs. Every attempt should be made to achieve an acceptable reduction while preserving the blood supply in this region. Careful monitoring is required in the follow-up period to timely recognize and treat complications such as avascular necrosis, non-union, angular deformities, and limb length discrepancy.

Salter–Harris IV injury of distal tibial physis along with sagittal plane talar body fracture may be an occult combination in physeal injuries of children and requires high index of suspicion for diagnosis to avoid missing the injury.

References

- 1.Hynes D, O’Brien T. Growth disturbance lines after injury of the distal tibial physis. Their significance in prognosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1988;70:231-3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wuerz TH, Gurd DP. Pediatric physeal ankle fracture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2013;21:234-44. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thermann H, Schratt HE, Hufner T, Tscherne H. Foot fractures in children. Unfallchirurg 1998;101:2-11. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rammelt S, Godoy-Santos AL, Schneiders W, Fitze G, Zwipp H. Foot and ankle fractures during childhood: Review of the literature and scientific evidence for appropriate treatment. Rev Bras Ortop 2016;51:630-9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniels TR, Smith JW. Talar neck fractures. Foot Ankle 1993;14:225-34. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kothadia S, Birole U, Ranade A. Paediatric Salter-Harris Type IV injury of distal tibia with talus fracture. BMJ Case Rep 2017;2017:222226. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crosswell S, Rhee SJ, Wagner WW. Unusual fracture combination in a paediatric acute ankle (combined medial talar compression fracture with medial malleolus fracture in an immature skeleton): A case report. J Surg Case Rep 2014;10:rju100. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meier R, Krettek C, Griensven M, Chawda M, Thermann H. Fractures of the talus in the pediatric patient. Foot Ankle Surg 2005;11:5-10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pearse MF, Fowler JL, Bracey DJ. Fracture of the body of talus. Injury 1991;22:155-6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rammelt S, Zwipp H. Talar neck and body fractures. Injury 2009;40:120-35. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Launay F, Barrau K, Petit P, Jouve JL, Auquier P, Bollini G. Ankle injuries without fracture in children. Prospective study with magnetic resonance in 116 patients. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 2008;94:427-33. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Endele D, Jung C, Bauer G, Mauch F. Value of MRI in diagnostic injuries after ankle sprains in children. Foot Ankle Int 2012;33:1063-8. [Google Scholar]