Matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation or MACI is a successful treatment option for symptomatic trochlea chondral defects following a suprapatellar approach for tibial intramedullary nailing placement.

Dr. John G Lane, Musculoskeletal and Joint Research Foundation, 3750 Convoy Street #116, San Diego - 92111, California, United States. E-mail: jglane@san.rr.com

Introduction:Intramedullary nailing remains the most common method of treatment for tibial shaft fractures. The suprapatellar technique has proven to be useful in gaining and maintaining alignment, especially in proximal one-third tibia shaft fractures. It has been adopted by many surgeons taking trauma call, because it requires less set-up time and allows the surgery to be done with less assistance. We present a case of a femoral trochlea lesion following the placement of a reamed suprapatellar intramedullary nail for fixation of a tibial shaft fracture.

Case Presentation:An active 33-year-old male with no prior history of knee pain sustained a distal tibial shaft fracture and was treated with suprapatellar intramedullary nail fixation. Five months later, he underwent revision surgery with exchange nail placement and reaming via an infrapatellar technique for delayed healing of the fracture with subsequent successful healing. The patient, otherwise healthy, continued to experience persistent anterior knee pain with clunking and inability to arise from a flexed knee position approximately 18 months post-surgery. Magnetic resonance imaging and arthroscopic evaluation of the joint were performed, and a full-thickness cartilage lesion was identified in the central portion of the femoral trochlear groove.

Conclusion: The purpose of the present case is to bring awareness to the fact that the suprapatellar approach to intramedullary nailing tibial shaft fracture fixation can be accompanied by trochlear articular cartilage damage, which can be successfully treated with cartilage restoration.

Keywords: Knee, ACI, autologous chondrocyte implant, trochlear lesion, suprapatellar intramedullary nailing.

Intramedullary nailing (IMN) remains the most common method of the treatment for tibial shaft fractures. Routinely, IMN is performed using an infrapatellar entry point. However, a new approach was developed using a suprapatellar entry point that, according to recent literature, has proven to be superior in improving alignment, especially in proximal one-third tibia fractures [1]. As a result, the suprapatellar technique (SPT) has been adopted by many surgeons taking trauma call, because it requires less set-up time and allows the surgery to be done with less assistance. The infrapatellar approach requires the knee joint to be flexed 90° degrees or greater, resulting in a higher risk of malalignment. In comparison, the suprapatellar approach involves a semi-extended position with the knee bent approximately 15° degrees [2]. This approach allows for better alignment of tibial fractures and a consequently higher rate of union [3]. It has been shown to decrease the risk of malalignment, and overall yield better functionality after recovery than the infrapatellar approach to IMN [4]. The suprapatellar approach to IMN uses the femoral trochlear groove as a guide for nail insertion. While recent literature confirms the benefits of the suprapatellar approach to IMN, few cases have identified the potential risk of cartilage damage to the femoral trochlea [2, 5, 6]. Concerns regarding chondral damage with a suprapatellar approach are the main reason why an extra-articular parapatellar approach has been introduced [7]. Here, we present a case of a trochlear chondral lesion caused by suprapatellar IMN.

A healthy, and active 33-year-old male with no metabolic abnormalities presented to the clinic with persistent knee and tibial pain 4 months post-initial suprapatellar IMN of his left tibia at an outside facility for a distal tibial shaft fracture. The patient was noted to have little callus formation with a persistent fracture line and was diagnosed with a delayed union 5 months post-fracture fixation. He required revision surgery with exchange nailing, using an infrapatellar approach. Despite fracture healing, the patient was noted to have persistent knee pain with clunking on extension. A decision was made to have an arthroscopic evaluation performed. The patient was noted to have full-thickness articular cartilage loss in the central aspect of the femoral trochlea.

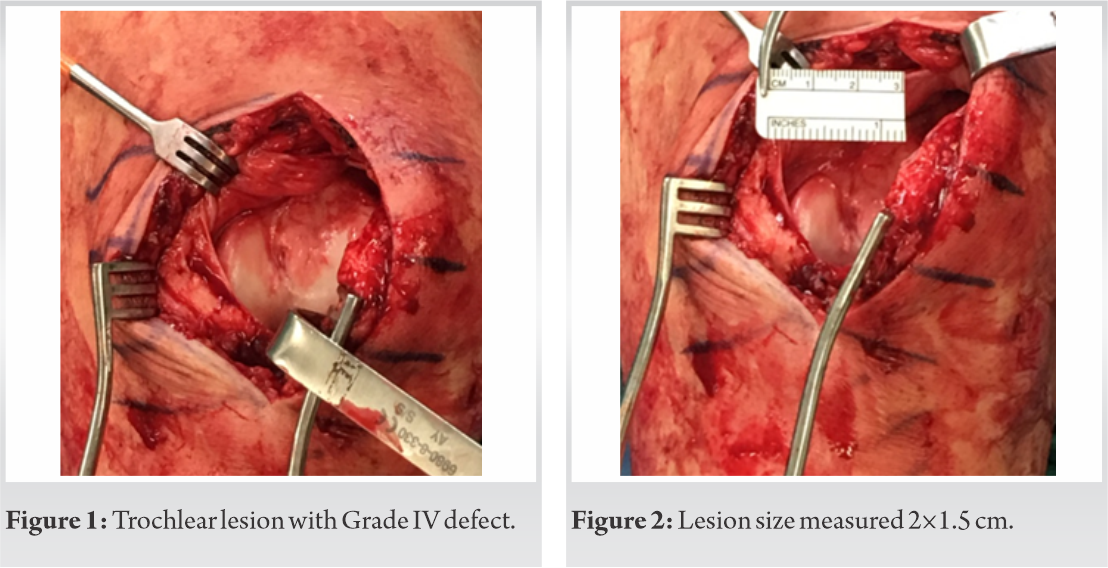

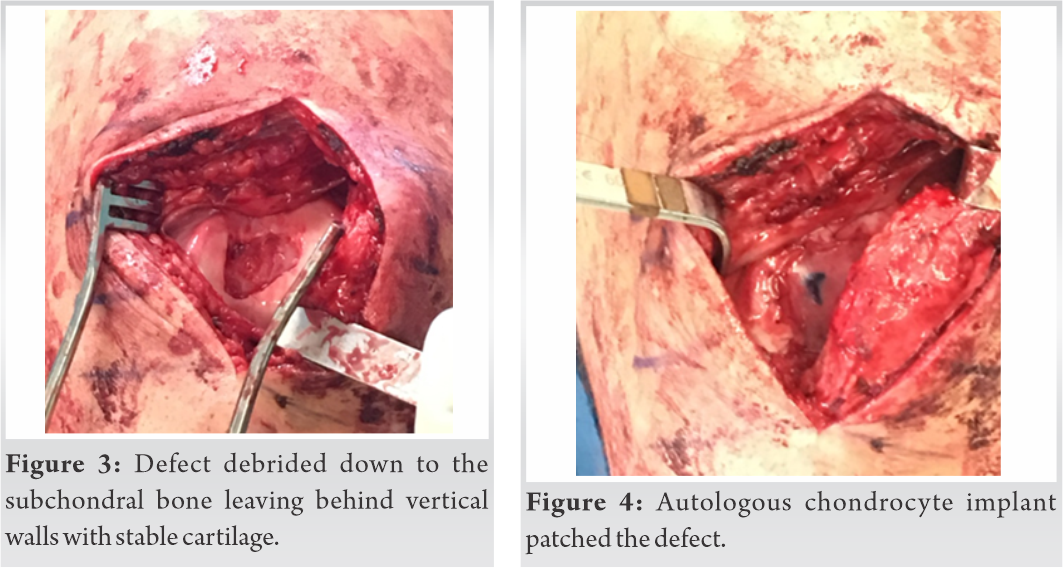

As time passed by, 5 months after the revision surgery and 10 months after the initial procedure, the patient continued to report substantial pain and limited range of knee motion. He was referred for a post-operative course of physical therapy, but despite the physiotherapy, the patient continued with complaints of constant pain with popping, crepitus, and quadriceps weakness due to pain. A patellofemoral brace was prescribed to the patient in an attempt to improve patellofemoral symptoms. Three months after wearing the brace, the patient continued to report unchanged symptoms. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was ordered, which demonstrated diffuse thinning of the trochlear articular cartilage. The patient underwent a knee arthroscopy with hardware removal, debridement, and cartilage harvesting for implantation. The cartilage lesion was evaluated, and it was noted to be 1.5 cm x 2 cm (Fig. 1, 2). Various treatment options for cartilage restoration were considered. Due to the undulating topography of the trochlea with normal appearing subchondral bone, autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) was selected. Fresh osteochondral allograft (OCA) was considered; however, due to the specific shape of the trochlea, locating a fresh OCA of similar shape would have been logistically challenging, and given the young age of the patient, the preference fell on the cell-based therapy. Cartilage was harvested from the notch area in the amount of approximately 200 mg of healthy tissue and shipped to the lab (Vericel, Cambridge, Massachusetts, US). The active ingredients of ACI (Carticel; Vericel, Cambridge, Massachusetts) are autologous cultured chondrocytes propagated in cell culture. Each carticel vial of autologous cultured chondrocytes contains approximately 12 million cells per vial. Carticel use in combination with collagen membrane is considered the 2nd generation of ACI. For the 2nd generation ACI, a type I/III bilayer collagen membrane (Bio-Gide; Geistlich Pharma) was used that resorbs entirely within a few months of implantation. First, the defect template was placed on the collagen membrane and cut to size, after which membrane was placed into the defect, secured with 6-0 Vicryl sutures and fibrin glue, and injected with autologous chondrocytes. The length of time between the biopsy and the implantation of ACI may vary depending on many factors, including the quality and number of cells obtained from the biopsy. On average, this will take 6 weeks; however, cells can be held in storage until a convenient date for surgery is agreed upon between the patient and the surgeon. Seven months later, an autologous chondrocyte implant procedure was performed once authorization was obtained due to ongoing knee pain. (Fig. 3, 4).

At a 2.5-year follow-up, the patient reported significant improvement in the knee symptoms, which allowed him to return to weightlifting, including squatting with weights. Therefore, no additional investigation was necessary.

The development of the suprapatellar approach to IMN of tibial fractures has resulted in improved alignment, union rates, and function [3]. The potential risks of the SPT have been widely overshadowed by its proven benefits when compared to the infrapatellar approach. Although risks have been hypothesized, a few cadaveric and clinical studies have been conducted and established the limitations and consequences of the suprapatellar approach to IMN [4, 7]. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses demonstrated significant reduction in total blood loss, post-operative knee pain, reduction in fluoroscopy exposure, and improvement in knee scores [8]. Although there seemed to be no significant differences in pain, disability, or knee range of motion, a few cases documented articular changes and evidence of chondromalacia on MRI [5]. Suprapatellar IMN is commonly associated with anterior knee pain [9]. However, the true cause remains unknown. An ultrasound study found no anatomical differences of the patellar tendon when varying paratendinous or transtendinous approaches to IMN, suggesting that anterior knee pain is independent of the tibial IMN approach used [10]. There has been concern about the potential articular cartilage damage to the patellofemoral joint when using the suprapatellar IMN approach. Studies have evaluated chondrocyte stability when subjected to various amounts of stress and impact [11, 12], and revealed no evidence of chondrocyte death or structural damage until stress levels of 25 MPa were reached [11); however, chondrocyte apoptosis may start at as low as 4.5 MPa [12]. A cadaveric study assessed the degrees of patellofemoral contact pressures resulting from suprapatellar IMN. The results indicated that although the pressure sustained from suprapatellar nail insertion was higher ≈ 2 MPa, it was still below the pressure values that were identified to cause chondrocyte damage in former studies [13]. The clinical outcomes of the suprapatellar approach have been evaluated in the recently published systematic review and meta-analysis [8]. To the best of our knowledge, only one clinical study of suprapatellar IMN has attempted to evaluate the clinical outcomes of suprapatellar IMN. Sanders et al. [14] arthroscopically identified two patients with Grade II chondromalacia limited to the trochlear groove immediately after surgery. Via MRI, however, it was determined that the articular damage was reversed by 1-year post-surgery. Due to these results, it was concluded that there was no significant effect of the suprapatellar approach to IMN on the patellofemoral joint. The authors stated that a limitation to this study was the late introduction of arthroscopic evaluation of the joint [14]. In the Chan et al. paper [5], 5 of the 11 patients had evidence of chondromalacia on MRI. However, there was no correlation between chondromalacia and either prenail or postnail insertion arthroscopy. In addition, no patient in the suprapatellar group with postnail insertion arthroscopic changes had patellofemoral joint pain at 1 year. Our case, in contrast to these results, did not indicate any reversal of the damage caused by the suprapatellar IMN procedure. Instead, a full-thickness cartilage lesion was identified and continued to generate pain, discomfort, and limit his movement over 18 months post-surgery. An ACI autologous chondrocyte implantation procedure allowed the patient to achieve significant improvement in his knee pain and return to weightlifting, including squatting with weights at 2.5 years post-ACI. Awareness of the potential complications of the procedure and knowledge of the appropriate treatment will bring the suprapatellar approach to IMN to a safer standard and will allow for peace of mind of the practitioner.

Awareness of the potential complication of the suprapatellar approach with potential articular cartilage injury and knowledge of the various treatment options for chondral injury, if it occurs, will facilitate care of patients with tibial fractures in consideration of nail placement and treatment of those patients who undergo suprapatellar nail placement with ongoing anterior knee pain.

When patients note ongoing patellofemoral knee pain following tibial fracture fixation with a suprapatellar tibial IMN approach, one should consider the presence of a chondral defect in the trochlea and note that this trochlear articular cartilage damage can be easily managed with the application of ACI.

References

- 1.Chen X, Xu HT, Zhang HJ, Chen J. Suprapatellar versus infrapatellar intramedullary nailing for treatment of tibial shaft fractures in adults. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e11799. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tornetta P. Semiextended position of intramedullary nailing of the proximal tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996;328:185-9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avilucea FR, Triantafillou K, Whiting PS, Perez EA, Mir HR. Suprapatellar intramedullary nail technique lowers rate of malalignment of distal tibia fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2016;30:557-60. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang C, Chen E, Ye C, Pan Z. Suprapatellar versus infrapatellar approach for tibia intramedullary nailing: A meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2018;51:133-9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan DS, Serrano-Riera R, Griffing R, Steverson B, Infante A, Watson D, et al. Suprapatellar versus infrapatellar tibial nail insertion: A prospective randomized control pilot study. J Orthop Trauma 2016;30:130-4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernigou P, Cohen D. Proximal entry for intramedullary nailing of the tibia. The risk of unrecognised articular damage. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000;82:33-41. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zamora R, Wright C, Short A, Seligson D. Comparison between suprapatellar and parapatellar approaches for intramedullary nailing of the tibia. Cadaveric study. Injury 2016;47:2087-90. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Packer TW, Naqvi AZ, Edwards TC. Intramedullary tibial nailing using infrapatellar and suprapatellar approaches: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Injury 2021;52:307-15. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Court-Brown CM, Gustilo T, Shaw AD. Knee pain after intramedullary tibial nailing: Its incidence, etiology, and outcome. J Orthop Trauma 1997;11:103-5. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Väistö O, Toivanen J, Paakkala T, Järvelä T, Kannus P, Järvinen M. Anterior knee pain after intramedullary nailing of a tibial shaft fracture: An ultrasound study of the patellar tendons of 36 patients. J Orthop Trauma 2005;19:311-6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Repo RU, Finlay JB. Survival of articular cartilage after controlled impact. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1977;59:1068-76. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loening AM, James IE, Levenston ME, Badger AM, Frank EH, Kurz B. Injurious mechanical compression of bovine articular cartilage induces chondrocyte apoptosis. Arch Biochem Biophys 2000;381:205-12. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gelbke MK, Coombs D, Powell S, DiPasquale TG. Suprapatellar versus infra-patellar intramedullary nail insertion of the tibia: A cadaveric model for comparison of patellofemoral contact pressures and forces. J Orthop Trauma 2010;24:665-71. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanders RW, DiPasquale TG, Jordan CJ, Arrington JA, Sagi HC. Semiextended intramedullary nailing of the tibia using a suprapatellar approach: Radiographic results and clinical outcomes at a minimum of 12 months follow-up. J Orthop Trauma 2014;28:S29-39. [Google Scholar]