Tissue turnover in the Achilles tendon is a very slow process. However, the tendon is capable of retaining its regenerative capacity even in extremely critical biological situations

Dr. Andrea Bisciotti, Orthopaedics of the Knee and Sport Traumatology Unit, Humanitas Research Hospital, Via Alessandro Manzoni 56, Rozzano, 20089, Italy. E-mail: andrea.bisciotti1@gmail.com

Introduction: Tendon tissue turnover is a very slow process. However, some tendons show very unique regeneration capabilities. The Achilles tendon regeneration and maturation process occurs uniformly and centripetally along the entire the length of the neo-tendon.

Case Report: The present case report describes a complete regeneration of the Achilles tendon in a 54-year-old patient with a reinjury to the Achilles tendon following open tenorrhaphy surgery. The regenerative process had a positive outcome despite the patient suffering, at the time, from an infection caused by Cutibacterium acnes.

Conclusion: This case report is a paradigmatic example of how the Achilles tendon is able to maintain its regenerative capacity even in extremely critical biological situations such as after an infection. However, the issue concerning the biological characteristics of the regenerated tendon remains open.

Keywords: Achilles tendon, post-surgical infection, regenerative process, tendon histology, mechanical properties.

The Achilles tendon has an exceptional ability to withstand the tensional forces created during movement. The in vivo peak force withstood by the Achilles tendon has been measured at more than 2.200 Newtons (N), resulting in a linear distribution in the order of 50–100 N/mm [1]. However, during activities such as running, the Achilles tendon transmits forces that are approximately seven times the subject’s body weight. This represents a huge increase to the forces that are normally at play in maintaining the upright position which are about half the body’s weight [1]. Nonetheless, despite its mechanical strength, this is the tendon that breaks most frequently [1]. An Achilles tendon rupture is more frequent in the male population than in the female population and presents two peaks of high incidence: A first peak is seen in the young sports population and a second peak appears in middle-aged people [1]. In recent years, there has been an increase in the number of these ruptures probably due to an increase in sport activities, especially in the so-called “weekend warrior” population [2]. Treatment may be conservative or surgical. In the case of surgical solutions, the principal complications are the risk of re-injury, although less frequent than after conservative treatment, and complications arising from superficial and deep infections. The management of deep infections complicates the patient’s affliction. There is no agreed procedure for treating nascent infections but most literature agrees on the administration of antibiotics and the surgical cleaning and debridement of infected tissues, followed by a second step in which tendon transfer surgery is programmed to replenish any hollows left after cleaning [3]. Tendon tissue turnover is a very slow process that can be defined as “bradytrophic” [4]. However, despite this aspect, several tendons show very unique tendencies toward regeneration [5]. Paradoxically, in some clinical frameworks, the capacity of the tendon to regrow can present negative aspects. A paradigmatic example is represented by the adductor longus tendon which, when affected by severe tendinopathy and subjected to partial or total tenotomy, has the ability to form fibrotic bridges which expose patients, especially athletes, to the risk of recurring injuries [5]. However, the ability of tendons to regrow can also have positive connotations. An example is represented by the semitendinosus (ST) and gracilis (G) tendons: After being harvested for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, long-term follow-up tests showed that these ligaments had the ability to regrow and partially recover their biomechanical properties and thus recuperate function and the ability to transmit muscle strength [6, 7]. In this case report, we discuss an unusual and surprising example of Achilles tendon regrowth.

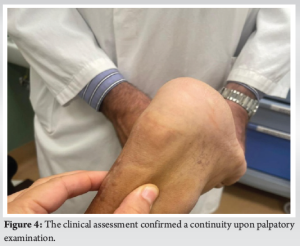

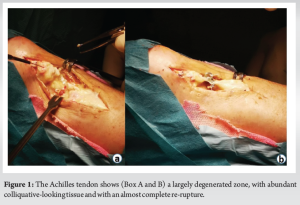

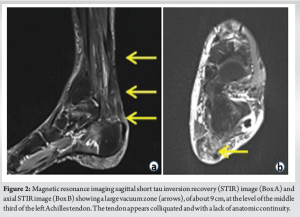

A 54-year-old patient with reinjury to the Achilles tendon following open tenorrhaphy surgery came to our attention. The first clinical signs and symptoms of pain and initial functional impotence in the left Achilles tendon dated to the beginning of March 2021. Clinical and imaging assessments allowed for a diagnosis of left Achilles tendinopathy to be formulated. In June 2021, in the absence of trauma, the patient experienced an episode of stabbing pain in the left Achilles tendon with immediate and total functional impotence: A diagnosis of total rupture of the left Achilles tendon was made. Seven days later, open tenorrhaphy surgery was performed. In the post-operative period, the patient’s foot was immobilized in the plantar flexion position for 1 month after which a rehabilitation period was followed which progressively enabled the complete range of motion and normal gait mechanics of the ankle to be regained. Two months after surgery, eccentric exercises were introduced. During the execution of an eccentric exercise, a new acute stabbing pain in the left Achilles tendon was reported. Consequently, an ultrasound and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were performed which revealed another episode of total tendon injury due to the improper rehabilitation (i.e. early introduction of eccentric exercises). The patient’s foot was therefore again immobilized in the plantar flexion position and another open tenorrhaphy operation using the typical Kessler suture method was carried out after 10 days. About 25 days after surgery, pain was gradually experienced, swelling developed, and a secreting fistula appeared. Swabs and samples of the secretion material were collected with the result of positivity for Cutibacterium acnes. Antibiotic therapy was started for about 2 weeks without resolution of the clinical condition and normalization of laboratory indices. It was therefore decided to proceed with open surgery for cleaning and debridement. During surgery, the tendon appeared largely degenerated and remodeled, with abundant colliquative-looking tissue and with an almost complete re-rupture (Fig. 1). The colliquated tissue was completely removed and 3 tissue samples were sent for culture examination after having undergone wash-out of the indwelling antibiotic. After cleaning and debridement, a solution of continuity of about 9 cm was observed. Following the renewed positivity of the culture tests, the patient underwent two and a half months of antibiotic treatment with Augmentin 1 gram 3 capsules per day and clindamycin 300 milligrams 3 capsules per day. The therapy was maintained for 15 days until the wound and laboratory indicators were normalized. In the post-operative period, the patient walked with Canadian crutches for 120 days. Sessions on the stationary bike were introduced in the rehabilitation plan after 45 days. After 90 days, a control MRI was performed (Fig. 2). During this period, the patient was monitored weekly by the reference surgeon who was awaiting to schedule the next tendon transfer surgery. In the meantime, the patient continued the rehabilitation plan. After 120 days, he was able to perform training sessions with a road mountain bike and then a racing bike (for a total of about 1 h 30 min a day, 5 times a week). A new MRI examination, performed after 11 months, showed an anatomical continuity of the tendon and a complete disappearance of the vacuum zone (Fig. 3). Clinical assessment confirmed a continuity upon palpatory examination (Fig. 4) The triceps surae dynamometric test showed a value of 118 kg on the left versus 153 on the right (difference: 29.6 %). The patient was able to perform the heel raise test and showed normal gait mechanics. Given the positive response to the clinical and imaging examination, it was decided to continue the conservative path with periodic clinical checks every 6 months. At the 18-month follow-up, the patient displayed excellent clinical conditions and did not exhibit pain neither experience an alteration in gait mechanics nor a decrease in muscle strength decrease.

This case report shows how tendons manage to maintain their reparative capacity even in extremely adverse biological conditions such as after an infection. In an 1992 MRI assessment, Cross et al. [8] had already reported the regeneration of the ST and the G tendon after their harvesting for ACL reconstruction. Similarly, many authors have documented the regrowth of the adductor longus tendon after partial or total tenotomy [9-11]. Initially, it was suggested that the tendon regeneration process progressed from the proximal to the distal direction [12]. For this reason, Leis et al. [13] coined the term “lizard tail phenomenon”. However, subsequent studies showed that, following harvesting for ACL reconstruction, the ST and G tendons in particular matured uniformly along the harvested site [14]. Otoshi et al., [15] specifically studied the Achilles tendon regrowth using a murine model and described a regeneration similar to that of the ST and G tendons, in which the regeneration and maturation process take place uniformly along the length of the regenerated tendon. The authors observed that the hematoma scaffold enhances the migration of fibroblast precursor cells from the surrounding peritendinous tissue and from the tendon sheath. Based on these observations, the authors concluded that the Achilles tendon regeneration and maturation process occurs uniformly along the length of the neo-tendon and not in a proximal to distal fashion as suggested by the lizard tail metaphor. Indeed, subsequent studies [5, 16] showed that the Achilles tendon repair took place in a centripetal direction from the peripheral tissue toward the central zone along the entire length of the neo-tendon. This particular type of centripetal regrowth is well described by the doughnut metaphor [5]. In this metaphor, the doughnut ring is the Achilles tendon’s peripheral zone formed by aligned fibrillar structures, and the doughnut hole is the tendon’s central area of disorganization [5]. In agreement with this metaphor, during the reparative process, the Achilles tendon shows a progressive reduction and centralization of the fibrillar disorganization area and thus the progressive disappearance of the doughnut hole. At the same time, the tendon shows a centripetal increase in the peripheral area consisting of healthy tendon tissue [5,17]. However, one question still remains open. Is the quality of the regenerated tendon tissue biologically comparable to that of the native tendon tissue? In animal models, the biomechanical strength in the regenerated ST [18] and Achilles tendon [15] is inferior to that of the native tendon at the 1-year follow-up but shows a trend of increasing strength over time [13]. To the best of our knowledge, there are no human model studies focused on the histological examination of the regenerated Achilles tendon to date in literature. For this reason, further prospective long-term studies evaluating the histological features of the regenerated Achilles tendon are needed. In any case, awareness of the regenerative capacity of the Achilles tendon represents an important point of reflection when considering the medical approach to adopt in those patients for which the surgical approach is not risk-free. Indeed, in such situations, a conservative and “wait-and-see” approach with frequent follow-ups can benefit from the assistance of Nature and tendon biology which, although probably not perfect in histological terms, could provide an important help from a clinical point of view.

Tissue turnover in the Achilles tendon is a very slow process that can be defined as “bradytrophic”. However, the tendon is capable of retaining its regenerative capacity even in extremely critical biological situations such as after an infection. However, the issue concerning the biological characteristics of the regenerated tendon compared to the original tendon tissue, still remains open.

This case report is a paradigmatic example of how the choice of conservative treatment for Achilles tendon rupture may represent a valid alternative to surgical treatment in all middle-aged patients (i.e. past their fifties) with limited functional demands. Obviously, the patient must be informed about the risks and benefits that this choice entails.

References

- 1.Waggett AD, Ralphs JR, Kwan AP, Woodnutt D, Benjamin M. Characterization of collagens and proteoglycans at the insertion of the human Achilles tendon. Matrix Biol 1998;16:457-70. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarantino D, Palermi S, Sirico F, Corrado B. Achilles tendon rupture: Mechanisms of injury, principles of rehabilitation and return to play. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol 2020;5:95. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winters B, Da Rin de Lorenzo F, Beck D. What is the treatment “algorithm” for infection after Achilles tendon repair/reconstruction? Foot Ankle Int 2019;40(1_suppl):71S-3. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang JH. Mechanobiology of tendon. J Biomech 2006;39:1563-82. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bisciotti GN, Bisciotti A, Auci A, Bisciotti A, Eirale C, Corsini A, et al. Achilles tendon repair after tenorraphy imaging and the doughnut metaphor. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023;20:5985. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kannus P, Józsa L. Histopathological changes preceding spontaneous rupture of a tendon. A controlled study of 891 patients. J Bone Joint Surg 1991;73:1507-25. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voleti PB, Buckley MR, Soslowsky LJ. Tendon healing: Repair and regeneration. Annu Rev Biomed Eng 2012;14:47-71. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cross MJ, Roger G, Kujawa P, Anderson IF. Regeneration of the semitendinosus and gracilis tendons following their transection for repair of the anterior cruciate ligament. Am J Sports Med 1992;20:221-3. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schilders E, Dimitrakopoulou A, Cooke M, Bismil Q, Cooke C. Effectiveness of a selective partial adductor release for chronic adductor-related groin pain in professional athletes. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:603-7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Queiroz RD, de Carvalho RT, de Queiroz Szeles PR, Janovsky C, Cohen M. Return to sport after surgical treatment for pubalgia among professional soccer players. Rev Bras Ortop 2014;49:233-9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bisciotti GN, Chamari K, Zini R, Corsini A, Bisciotti AL, Bisciotti AN, et al. Adductor longus tenotomy in the treatment of groin pain syndrome in athletes: A systematic review. Joints 2023b;1:e602. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rispoli DM, Sanders TG, Miller MD, Morrison WB. Magnetic resonance imaging at different time periods following hamstring harvest for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 2001;17:2-8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leis HT, Sanders TG, Larsen KM, Lancaster-Weiss KJ, Miller MD. Hamstring regrowth following harvesting for ACL reconstruction: The lizard tail phenomenon. J Knee Surg 2003;16:159-64. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carofino B, Fulkerson J. Medial hamstring tendon regeneration following harvest for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: Fact, myth, and clinical implication. Arthroscopy 2005;21:1257-65. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otoshi K, Kikuchi S, Ohi G, Numazaki H, Sekiguchi M, Konno S. The process of tendon regeneration in an Achilles tendon resection rat model as a model for hamstring regeneration after harvesting for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy 2011;27:218-27. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barfod KW. Achilles tendon rupture; assessment of non-operative treatment. Dan Med J 2014;61:B4837. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cook JL, Rio E, Purdam CR, Docking SI. Revisiting the continuum model of tendon pathology: What is its merit in clinical practice and research? Br J Sports Med 2016;50:1187-91. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gill SS, Turner MA, Battaglia TC, Leis HT, Balian G, Miller MD. Semitendinosus regrowth: Biochemical, ultrastructural, and physiological characterization of the regenerate tendon. Am J Sports Med 2004;32:1173-81. [Google Scholar]