Early recognition of deep post-operative infection coexisting with cerebrospinal fluid leak, followed by targeted antimicrobial therapy, temporary cerebrospinal fluid diversion, and staged dural repair, can eradicate pan‑resistant Enterobacter infection, close the leak, and preserve spinal instrumentation. A stepwise multidisciplinary strategy combining repeated meticulous debridement, culture‑directed therapy, and definitive dural repair prevents catastrophic sequelae and enables implant retention with durable clinical recovery.

Dr. Aditya A Agarwal, Department of Orthopaedics, Grant Government Medical College and Sir JJ Group of Hospitals, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: dradiagr@gmail.com

Introduction: Post-operative cerebrospinal fluid leakage and deep surgical site infection are challenging complications after instrumented lumbar fusion, and their coexistence – especially with multidrug-resistant organisms – increases morbidity while jeopardizing neural integrity and implant stability.

Case Report: A 65-year-old woman with diabetes mellitus and hypertension developed persistent wound discharge 1 month after L4–L5 decompression and fusion, with cultures revealing pan-resistant Enterobacter infection. Despite serial debridements and empirical antibiotics, she developed a refractory cerebrospinal fluid leak due to occult dural-tear confirmed intraoperatively with fluorescein localization. Management included repeated meticulous debridement, targeted intravenous and intrathecal colistin therapy, and temporary thecoperitoneal shunting for cerebrospinal-fluid diversion, followed by definitive dural repair with shunt removal that achieved complete infection control and leak resolution. At 2-year follow-up, she was asymptomatic with stable fusion and no recurrence.

Conclusion: Early recognition of deep infection and prompt multidisciplinary intervention are essential to prevent catastrophic sequelae after instrumented lumbar fusion. Tailored antimicrobial therapy, cerebrospinal fluid diversion, and staged surgical repair can clear infection and achieve durable dural healing while preserving spinal instrumentation.

Keywords: Cerebrospinal fluid leak, pan-resistant Enterobacter, spinal surgical site infection, lumbar fusion, multidisciplinary management.

Posterior-lumbar fusion is widely used for degenerative spinal pathology. Despite advances, post-operative complications remain a significant concern. Deep surgical-site infection (SSI) occurs in up to 2–20% of instrumented spine procedures and is associated with morbidity [1]. Risk factors include advanced age, diabetes, smoking, obesity, and revision surgery [1]. A meta-analysis of 41,624 instrumented cases found an overall SSI rate of 2.9% and identified transfusion, hypertension, osteotomy, and the number of fused levels as significant predictors, whereas age, smoking, and operative time showed no association [2]. The same analysis noted that reported infection rates in the literature vary from 0.2 to 16.1% and highlighted the multifactorial nature of SSI, underscoring the need for prospective studies to better define modifiable factors [2]. Early diagnosis using C-reactive protein and imaging and prompt debridement with targeted antibiotics is essential to salvage implants [1].

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage due to dural tears is another important complication. Incidence after lumbar surgery varies widely, with reports ranging from 2% to 20% [3]; a series of 3,179 lumbar-posterior surgeries found an incidence of 3.6% [3]. Risk factors for dural tears include trauma, tumor resection, and adhesions and multiple fusion levels, pre-operative epidural steroid injection, and advanced age increase risk [3]. Unrecognized CSF leaks can lead to pseudomeningocele, delayed healing, infection, and meningitis, management requires meticulous dural repair, bed rest, drainage, and rehydration [3,5].

Management is further complicated by the emergence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacter spp. and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales are considered priority pathogens, and therapeutic options are limited to last-line agents such as polymyxins (colistin or polymyxin B) and tigecycline; resistance to these drugs is increasing [7]. Global colistin-resistance rates range from 3 to 28% for Acinetobacter baumannii and 2.8–10.5% for Klebsiella pneumoniae, raising concerns about a pre-antibiotic era and prompting research into new drugs, combination regimens, and alternative therapies [8].

We report a case of lumbar fusion complicated by an occult dural tear with persistent CSF leak and a pan-resistant Enterobacter infection, illustrating the importance of early recognition, multidisciplinary management, and tailored antimicrobial therapy.

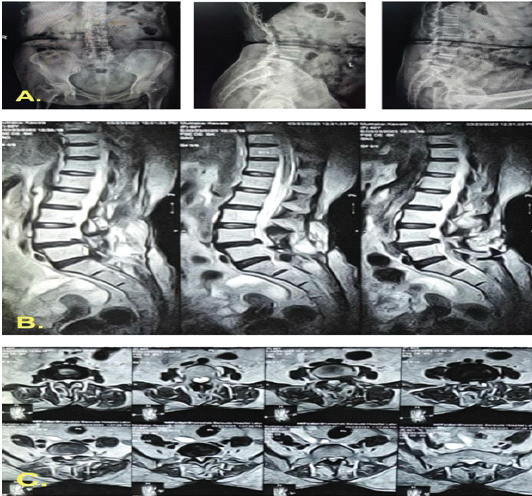

A 65-year-old woman with hypertension, diabetes mellitus (hemoglobin A1c [glycated hemoglobin] 6.8), ischemic heart disease, and a history of L4–L5 lumbar decompression in 2018 presented with chronic low back pain, neurogenic claudication, and urinary urge incontinence. Imaging revealed L4–L5 grade I post-laminectomy spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Pre-operative imaging of L4–L5 grade I spondylolisthesis with spinal canal stenosis. (a) Standing anteroposterior and lateral radiographs at presentation demonstrating L4–L5 spondylolisthesis. (b) T2-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging showing canal stenosis at the L4–L5 level. (c) T2-weighted axial magnetic resonance imaging at the same level illustrating circumferential dural sac compression.

Figure 2: Immediate post-operative imaging following lumbar fusion. Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs showing L4–L5 transpedicular screw-rod fixation with decompression and posterolateral fusion, demonstrating satisfactory implant position.

On August 29, 2023, she underwent L4–L5 transpedicular screw-rod fixation, decompression, and posterolateral fusion (Fig. 2). The procedure and early recovery were uneventful. She was mobilized on post-operative day (POD) 2, maintained on strict glycemic control, and discharged on POD 5, ambulating independently with satisfactory pain relief and stable blood glucose levels. The wound was healthy at suture removal on POD 14.

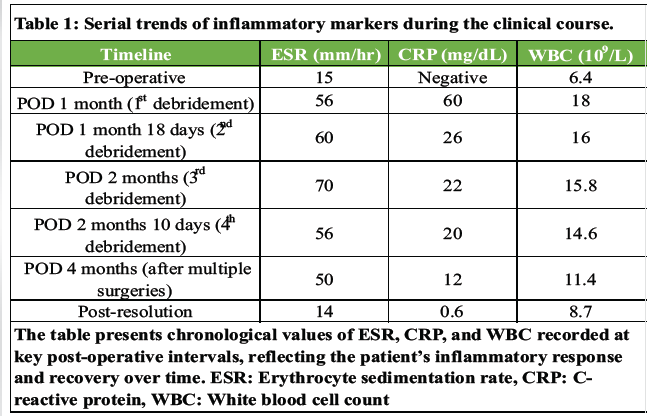

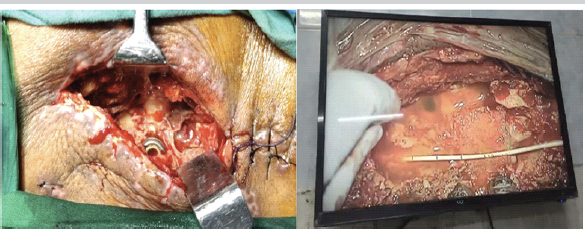

Four weeks later, she developed fever, increasing back pain, and difficulty walking. Examination revealed localized tenderness, swelling, and serosanguineous wound discharge. Inflammatory markers were elevated (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] 56 mm/hr, C-reactive protein [CRP] 60 mg/L, WBC 18,800/μL). Serial ESR, CRP, and white blood cell [WBC] counts were monitored throughout her course, showing correlation with infection activity and subsequent normalization after targeted treatment and definitive CSF leak repair (Table 1). Ultrasound detected a fluid collection, from which 30 mL of serosanguineous fluid was aspirated. Emergency wound exploration and debridement were performed (Fig. 3), with thorough removal of necrotic tissue, biofilm, and infected graft, followed by copious irrigation. No dural tear or CSF leak was identified intraoperatively. Empirical antibiotics (piperacillin–tazobactam and amikacin) were initiated.

Table 1: Serial trends of inflammatory markers during the clinical course.

Despite temporary improvement, persistent serous drainage continued. Deep wound cultures later grew pan-resistant Enterobacter species. A second debridement under local anesthesia was performed at 1.5-month post-surgery, but discharge persisted. A third re-debridement, done 20 days later with neurosurgical assistance (Fig. 4), involved extending the laminectomy to L3. Intraoperative intrathecal fluorescein confirmed an occult CSF leak from the right L4 pedicle screw tract. Targeted intravenous colistin was started.

Figure 4: Third debridement with multidisciplinary management. Intraoperative image showing the third debridement performed collaboratively with the spine and neurosurgical teams. An epidural drain was placed for cerebrospinal fluid diversion, and targeted intravenous colistin therapy was continued for pan-resistant *Enterobacter* infection.

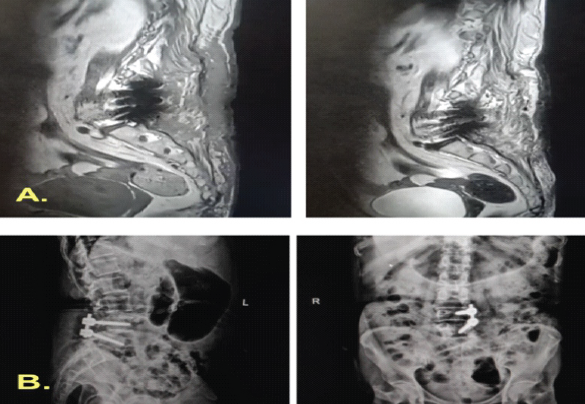

However, by 2.5-month post-index surgery, clear fluid discharge persisted, indicating a refractory CSF leak. A thecoperitoneal shunt was inserted, after which she was discharged. Two months later (4 months from the index procedure), she presented with meningitis and recurrent CSF leakage, suggesting shunt failure. Intrathecal colistin and temporary Mini Vac drainage were administered. Ultimately, 2 months after shunt placement, it was removed, and a primary dural repair was performed under general anesthesia (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Post-operative imaging following fifth debridement and definitive repair. Magnetic resonance imaging and radiographs obtained immediately after the fifth debridement and re-exploration demonstrate removal of the thecoperitoneal shunt and right-sided pedicle screws, with evidence of successful cerebrospinal-fluid leak repair and resolution of the collection.

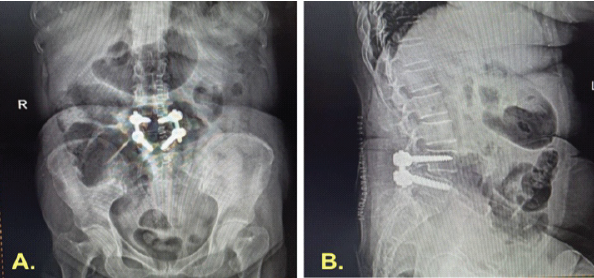

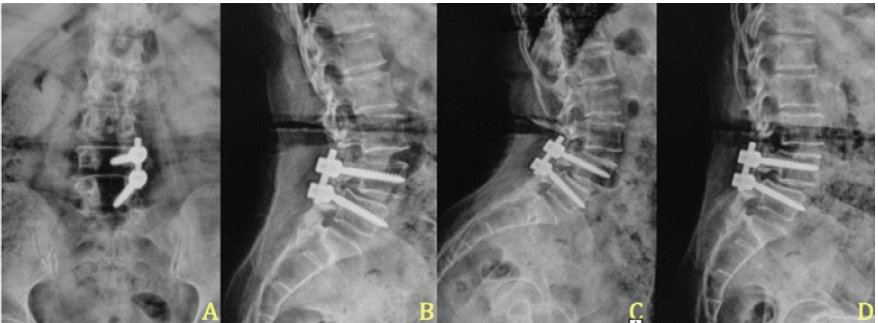

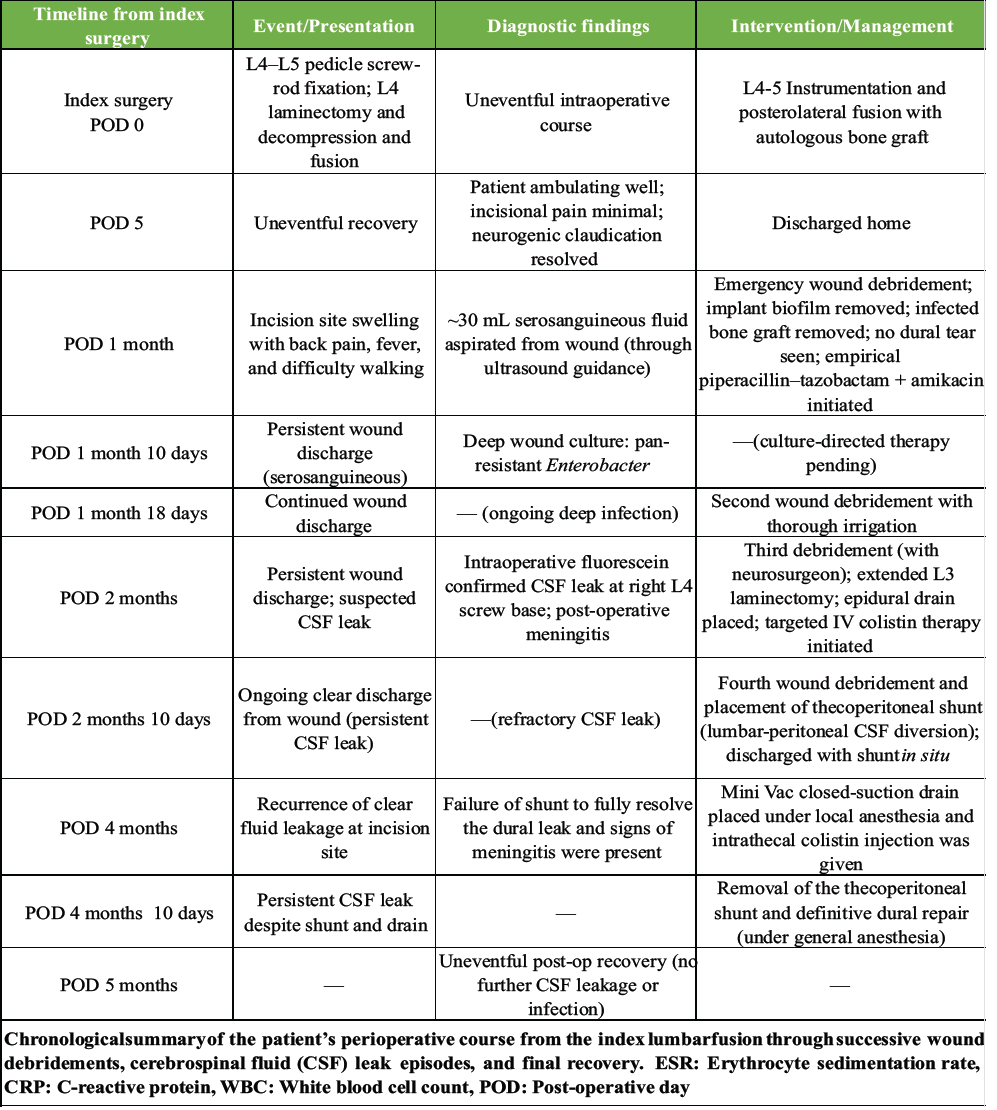

Following the definitive dural closure, the patient’s recovery was uneventful, with complete cessation of CSF leak and resolution of infection. At 2-year follow-up, radiographs confirmed stable fusion and alignment (Fig. 6). The chronological sequence of clinical events, diagnostic findings, and interventions is summarized in Table 2.

Figure 6: Two-year post-operative radiographic follow-up. (a and b) Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs obtained 2 years after surgery demonstrate proper implant placement, restored disc height, and maintained sagittal alignment. (c and d) Dynamic flexion and extension views at the same follow-up show no abnormal motion or listhesis across the fused segment, confirming stable fusion and construct integrity.

Table 2: Timeline of key clinical events and interventions

This case illustrates the complex interplay of post-operative deep infection and CSF leakage following lumbar fusion in a patient with advanced age, diabetes, and hypertension, all factors known to increase susceptibility to post-operative complications [1,2]. Early recognition of infection through clinical vigilance and ultrasound-guided aspiration enabled prompt initiation of empirical antibiotics and urgent surgical debridement, which remains a cornerstone of managing deep infections in instrumented spinal surgery [2,3]. Repeat debridements with meticulous removal of biofilm and infected graft material, while preserving stable instrumentation, are consistent with literature supporting retention of stable instrumentation following adequate debridement [3,9].

The identification of pan-resistant Enterobacter necessitated escalation to targeted intravenous colistin. Because systemic therapy alone often fails to achieve therapeutic CSF levels, adjunct intrathecal administration was utilized to enhance drug penetration and achieve effective microbial clearance, reflecting outcomes reported in similar multidrug-resistant infections [4].

Management of the occult dural tear and refractory CSF leak required a staged and multidisciplinary approach. Intrathecal fluorescein facilitated precise localization of the dural defect, guiding targeted surgical intervention. Temporary CSF diversion techniques — including epidural drainage, thecoperitoneal shunting, and closed-suction drainage — were crucial in controlling persistent leakage and reducing CSF pressure until definitive dural repair could be performed [3,6].

Such complex post-operative infections underscore the importance of a coordinated multidisciplinary approach involving spine surgeons, neurosurgeons, and infectious disease specialists to optimize antimicrobial therapy, facilitate timely re-interventions, and preserve spinal instrumentation [10].

This case highlights the complexity of managing concurrent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak and pan-resistant Enterobacter infection following lumbar fusion. Early identification of infection, repeated meticulous debridement, and the use of targeted intravenous and intrathecal colistin, combined with staged CSF diversion and definitive dural repair, were pivotal in achieving infection control and stable fusion. A multidisciplinary, stepwise approach remains essential for successful outcomes in such challenging post-operative spinal infections.

Early recognition of post-operative infection and timely multidisciplinary intervention are crucial in preventing catastrophic outcomes. Stepwise debridement, targeted antimicrobial therapy, and staged cerebrospinal fluid diversion followed by definitive dural repair can successfully eradicate infection, achieve leak closure, and preserve spinal stability even in cases involving panresistant organisms.

References

- 1. Kalfas F, Severi P, Scudieri C. Infection with spinal instrumentation: A 20-year, single-institution experience with review of pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention and management. Asian J Neurosurg 2019;14:1181-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Zhang X, Liu P, You J. Risk factors for surgical site infection following spinal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022;101:e31634. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Tang J, Lu Q, Li Y, Wu C, Li X, Gan X. Risk factors and management strategies for cerebrospinal fluid leakage following lumbar posterior surgery. BMC Surg 2022;22:30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Singh RK, Bhoi SK, Kalita J, Misra UK. Multidrug-resistant acinetobacter meningitis treated by intrathecal colistin. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2017;20:74-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Hodges SD, Humphreys SC, Eck JC, Covington LA. Management of incidental durotomy without mandatory bed rest: A retrospective review of 20 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999;364:208-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Khan MH, Rihn J, Steele G, Davis R, Donaldson WF 3rd, Kang JD. Postoperative management protocol for incidental dural tears during degenerative lumbar spine surgery: A review of 3,183 consecutive degenerative lumbar cases. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:2609-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Sheu CC, Chang YT, Lin SY, Chen YH, Hsueh PR. Infections caused by carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae: An update on therapeutic options. Front Microbiol 2019;10:80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Sharma J, Dongre V, Pati P, Chauhan A, Sethi S, Khullar S, et al. Colistin resistance and the management of drug resistant infections: An overview. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2022;2022:1562489. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Hegde V, Meredith DS, Kepler CK, Huang RC. Management of postoperative spinal infections. World J Orthop 2012;3:182-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Ghobrial GM, Cadotte DW, Williams K, Fehlings MG. Complications from instrumented spine surgery in older adults: Management strategies to improve outcomes. World Neurosurg 2015;84:703-11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]