In patients who may have difficulty complying with long-term follow-up, alternative methods to a two-stage arthroplasty should be recommended to treat prosthetic joint infections to prevent mechanical complications of retained spacers.

Dr. Li Yi Tammy Chan, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore. E-mail: chanlytammy@u.nus.edu

Introduction: Prosthetic joint infections (PJIs) remain an undesirable complication after total knee arthroplasties. Two-stage revision arthroplasty is the current standard of care for treating PJIs. However, the incidence of spacer retention for prolonged periods is increasing, with little known about its potential complications.

Case Report: We present a case of a 64-year-old female of Southeast Asian descent who had a cement spacer maintained in-situ for 7 years due to poor patient compliance with subsequent follow-up.

Conclusion: While patients have satisfactory functional outcomes with the cement spacer, it is not meant for permanent weight bearing. Two-stage revision arthroplasties are only as effective as patients’ compliance with subsequent follow-up and surgery. Clinicians must discourage patients from forgoing subsequent follow-up visits and surgery despite satisfactory function and quality of life with the cement spacer in situ to prevent complications related to prolonged retention of cement spacers.

Keywords: Total knee replacement, complications, implant retention, implant failure, bone loss.

With an increasing number of total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) performed, the incidence of complications is also rising. Prosthetic joint infections (PJIs) remain an undesirable complication of joint replacement procedures, occurring in 1–2% of primary TKAs [1]. Surgical options for the treatment of PJIs include debridement, antibiotics, implant retention (DAIR) procedures, and one- or two-stage revision arthroplasties. The current standard of care for the treatment of late-chronic PJIs involves two-stage revision arthroplasty. Two-stage revision arthroplasties involve the removal of the initial implants, thorough joint debridement, insertion of antibiotic-impregnated cement spacer, and intravenous antibiotics, followed by a second-stage arthroplasty [2]. Morbidity associated with spacer-related complications and multiple operations remains a concern [3]. There are limited studies investigating spacer-related complications and detailing the appropriate management of these complications. The aim of the cement spacer in two-stage revision is to deliver intra-articular antibiotics, maintain knee alignment, and prevent soft tissue contractures. Several types of cement spacers exist: static versus dynamic, pre-fabricated versus molded, and custom-made ones [4]. Known complications of articulating cement spacer insertion include implant loosening, cement spacer fractures, and cement debris [2]. Cement spacers used in the treatment of PJIs are typically implanted for 2–3 months, during which patients are given a course of culture-specific antibiotics and monitored for eradication of infection before second-stage revision arthroplasty. There have been instances where cement spacer implants are left in-situ longer than expected, but the long-term safety profile and longevity of cement spacer implants have not been well established. We present a rare case of concomitant cement spacer and peri-spacer fractures occurring in a patient 7 years after initial first-stage revision knee arthroplasty. We discuss the technical challenges and management of this patient, who successfully underwent revision surgery with knee megaprosthesis. We highlight the current literature surrounding the potential complications of cement spacers, risk factors for implant failure, and the fate of spacers implanted for longer periods than expected.

Our patient was a 64-year-old female of Southeast Asian descent with no significant past medical history. She underwent right TKA for primary knee osteoarthritis in 2013 (Fig. 1), utilizing the Stryker Triathlon Total Knee System (Stryker, Mahwah, New Jersey). Her post-operative recovery and rehabilitation were uneventful. Unfortunately, she developed a PJI 1 year later, confirmed by positive knee joint aspiration for beta-hemolytic Group G streptococci. She was treated with the DAIR procedure and 6 weeks of intravenous penicillin G, which led to the biochemical and clinical resolution of PJI. However, she was re-admitted the following year for a recurrence of right knee PJI. Repeat knee joint aspirations showed positive cultures again for pan-sensitive Group G streptococcus. A decision was made to perform a two-stage revision knee arthroplasty.

During the first-stage revision surgery, the arthroplasty implants were removed, followed by a thorough knee joint washout and debridement. Vancomycin-impregnated cement spacers were created via molds (COPAL® Exchange G Preformed Spacers, Heraeus Medical GmbH, Wehrheim, Germany) with Palacos R+G cement (Heraeus Medical GmbH, Wehrheim, Germany) and inserted (Fig. 2). The patient was treated with 6 weeks of intravenous penicillin G and allowed full weight-bearing ambulation 6 weeks after surgery. She was a follow-up outpatient and demonstrated a good recovery with resolution of infective symptoms and normalization of inflammatory markers. Serial radiological evaluations showed a stable cement spacer with no significant bone loss or fractures. However, she refused second-stage revision surgery despite repeated counseling and expressed that she was satisfied with her knee range of motion and functional status with the cement spacer. She was last reviewed in December 2016 and demonstrated a knee range of motion of 30–100° with an intact extensor mechanism, was ambulant with a walking frame, and was fully independent in activities of daily living. She declined further follow-up appointments.

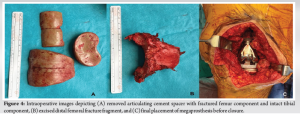

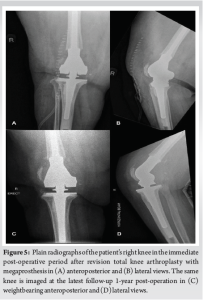

Seven years after first-stage revision surgery, she fell while walking to the toilet and presented with severe right knee pain. Clinical examination of the right knee showed tenderness over the distal femur, healed previous surgical scars, and no effusion, erythema, warmth, or sinus tracts. Radiological evaluation showed a displaced transverse distal femoral fracture with a concomitant fracture of the femoral component of the cement spacer (Fig. 3). Knee joint aspirate cultures pre-operatively were negative for infection. The patient underwent surgery for the removal of the cement spacer and revision arthroplasty with megaprosthesis (Fig. 4) under general anesthesia. Exposure was done via the previous midline incision and medial parapatellar approach. Intraoperative samples of surrounding soft tissue and bone were taken for culture and returned negative for infection. The cement spacer components were removed, and the knee joint was washed thoroughly. Additional caution is taken during the removal of cement spacer components to prevent fracturing of the bone intra-operatively. The interval between cement spacer and bone is first developed with an oscillating saw using a thin saw blade. Once the correct interval has been entered, flexible osteotomes are stacked under the cement space to lift the component off the bone cleanly. The distal femoral fragment was excised and measured to assess the resection level. The femoral fracture was exposed, and the femur was resected based on pre-operative and intraoperative measurements. The final implants used were the Depuy Limb Preservation System Size XXS Femoral Component with a 12 × 125 mm cemented stem and the Depuy Mobile Bearing Tibial Revision Tibia Size 1.5 with a 13 × 60 mm cemented stem and size XXS 14 mm tibial hinge insert (DePuy Synthes, Warsaw, IN) (Fig. 5). In the post-operative period, the patient was allowed to bear full weight as tolerated. Rehabilitation started on the first post-operative day, where the patient was able to achieve ambulation with the aid of a walking frame and gait training with 4-inch kerb step-ups. The patient was given a course of prophylactic antibiotics in view of the high risk of repeat PJI, as discussed with the inpatient infectious disease specialists. The patient was followed up in clinic for 6 weeks and 3 months postoperatively; however, defaulted on subsequent clinic visits. During the two follow-up visits, the patient recovered well and reported no pain or swelling. She was ambulating independently in the community with the aid of a walking frame. Clinical evaluation at the last follow-up visit showed healed wounds, a range of motion of 0–110°, good patella tracking, and stability with varus and valgus stress.

PJIs remain one of the leading causes of TKA revisions. Surgical options for the treatment of PJIs include DAIR and one- or two-stage revision arthroplasties. This patient initially underwent DAIR as she was diagnosed with an acute hematogenous PJI. Recent studies have shown that patients who undergo DAIR have a higher risk of septic re-revision compared to those who undergo an initial two-stage revision [5]. This was observed in our patient, who had a re-infection and subsequently had to undergo a two-stage revision arthroplasty. Two-stage revision surgery is a widely accepted treatment strategy, especially for late-chronic infections. The purpose of the cement spacer is for local delivery of antibiotics as well as maintaining the knee joint [6]. They have demonstrated good outcomes, with a reported infection clearance rate of 85–100% in various studies [7, 8]. However, spacers come with their own set of complications and limitations. Bone cement has a porous internal structure, which can act as a stress riser and lead to decreased strength [9]. Cement-on-cement articulating spacers can lead to wear, the generation of cement particles, implant fatigue, and cement spacer or peri-spacer fractures [10]. Risk factors for spacer fractures include surgeon-constructed spacers, higher antibiotic doses, non-congruent femoral component fit, and significant flexion contracture post-cement spacer insertion [10]. Risk factors for peri-spacer fractures include loose spacers, knee varus or valgus malignments, femoral notching, and poor bone quality around the spacer [10]. Antibiotic choice also affects the biomechanical properties of cement, with vancomycin-loaded bone cement showing favorable properties over cephazolin-loaded bone cement and meropenem-loaded bone cement demonstrating excellent biochemical properties [11]. Spacers are typically left in situ for 6–8 weeks to allow PJI to be treated with culture-directed antibiotics and skin wounds to heal. This universally accepted duration was first described by Insall et al. [12]. Sometimes, cement spacers are left for longer than expected due to continued infection, patient refusal for second-stage revision, medical conditions rendering the patient unfit for surgery, or other unforeseen circumstances such as operative postponements. Despite prolonged spacer retention, many patients, including ours, remain satisfied with their functional status while on the cement spacer. Alden reported 31 patients in his case series with an average implantation time of 26 weeks who were allowed full weight bearing with a cement spacer, of which only one femoral component dislocation and one spacer fracture were reported [6]. Choi et al. reported seven patients who were also allowed full weight bearing and range of motion on an articulating knee cement spacer insertion for more than 12 months. Six patients had well-functioning articulating spacers at an average follow-up of 42 months, with 1 spacer failure due to loosening at a 50-months follow-up [13]. Since patients are satisfied with the cement spacer, it may be a major factor in several patients forgoing or delaying further surgery. In more extreme cases, such as our patient, they may choose to default subsequent follow-up appointments, resulting in prolonged spacer retention. Spacer retention is an increasingly common complication, so much so that Hernandez et al. have proposed it as a 1.5–stage revision arthroplasty option for PJI treatment with an acceptable rate of infection recurrence and implant durability at a mean follow-up of 2.7 years [14]. Although patients can tolerate cement spacers for a longer implantation time than expected, spacers frequently fail for mechanical reasons compared to other reasons, such as re-infection [15]. It is expected that prolonged loading of the cement spacers will lead to progressive implant fatigue and bone wear, predisposing to implant loosening and spacer or peri-spacer fractures [16]. Even in the study by Hernandez et al., 20% of patients with spacer retention showed progressive radiolucent lines on follow-up radiographs, suggestive of progressive bone wear at the latest follow-up [14]. Therefore, cement spacers are not meant for prolonged weight bearing due to the risk of mechanical failure.

Overall, two-stage revision arthroplasties are only as effective as patients’ compliance with regular follow-up and subsequent surgery. Clinicians must make a conscious effort to educate patients regarding the risk of mechanical failure with retained spacers and discourage patients from forgoing subsequent follow-up visits and surgery despite achieving satisfactory function and quality of life with the cement spacer in-situ. In this case, the patient maintained the cement spacer in the right knee for 7 years without major complications. Bone wear and implant fatigue progressed insidiously, cumulating in fractures of both the cement spacer and distal femur after a low-energy fall. Regular evaluation for the development and progress of bone wear and implant fatigue is recommended in patients with prolonged retention of cement spacers. Further research is required to study the long-term safety profile of cement spacers left in-situ and the potential implications of retained spacers for subsequent surgeries.

There is a lack of data on the long-term safety profile of cement spacers left in-situ and the mechanical complications of retained spacers. In patients whose compliance with two-stage revision arthroplasty follow-up is expected to be difficult, regular evaluation for the progress of bone wear and implant fatigue is required. Alternatively, clinicians should recommend other methods to treat PJIs in the above patients to prevent mechanical complications of retained spacers.

References

- 1.Blom AW, Brown J, Taylor AH, Pattison G, Whitehouse S, Bannister GC. Infection after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004;86:688-91. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costanzo J, McCahon J, Tokarski AT, Deirmengian C, Bridges T, Fliegel BE, et al. Mechanical complications of hip and knee spacers are common. Cureus 2023;15:e38496. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garg P, Ranjan R, Bandyopadhyay U, Chouksey S, Mitra S, Gupta SK. Antibiotic-impregnated articulating cement spacer for infected total knee arthroplasty. Indian J Orthop 2011;45:535-40. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voleti PB, Baldwin KD, Lee GC. Use of static or articulating spacers for infection following total knee arthroplasty: A systematic literature review. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95:1594-9. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huffaker SJ, Prentice HA, Kelly MP, Hinman AD. Is there harm in debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention versus two-stage revision in the treatment of periprosthetic knee infection? Experiences within a large US health care system. J Arthroplasty 2022;37:2082-9.e1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alden KJ. Management of prosthetic joint infection following total knee arthroplasty with an articulating antibiotic knee spacer : An Early Experience. J Orthopaedic Experience & Innovation 2021;2. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasarhelyi E, Sidhu SP, Somerville L, Lanting B, Naudie D, Howard J. Static vs articulating spacers for two-stage revision total knee arthroplasty: Minimum five-year review. Arthroplast Today 2022;13:171-5. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munro JT, Garbuz DS, Masri BA, Duncan CP. Articulating antibiotic impregnated spacers in two-stage revision of infected total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012;94:123-5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaekel DJ, Day JS, Klein GR, Levine H, Parvizi J, Kurtz SM. Do dynamic cement-on-cement knee spacers provide better function and activity during two-stage exchange? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470:2599-604. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burnett RS, Kelly MA, Hanssen AD, Barrack RL. Technique and timing of two-stage exchange for infection in TKA. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007;464:164-78. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang LH, Feng YD, Zhang XW, Jin L, Zhou FL, Xu GH. Elution and biomechanical properties of meropenem-loaded bone cement. Orthop Surg 2021;13:2417-22. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Insall JN, Thompson FM, Brause BD. Two-stage reimplantation for the salvage of infected total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1983;65:1087-98. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi HR, Freiberg AA, Malchau H, Rubash HE, Kwon YM. The fate of unplanned retention of prosthetic articulating spacers for infected total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:690-3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernandez NM, Buchanan MW, Seyler TM, Wellman SS, Seidelman J, Jiranek WA. 1.5-Stage exchange arthroplasty for total knee arthroplasty periprosthetic joint infections. J Arthroplasty 2021;36:1114-9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petis SM, Perry KI, Pagnano MW, Berry DJ, Hanssen AD, Abdel MP. Retained antibiotic spacers after total hip and knee arthroplasty resections: High complication rates. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:3510-8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cai YQ, Fang XY, Huang CY, Li ZM, Huang ZD, Zhang CF, et al. Destination joint spacers: A similar infection-relief rate but higher complication rate compared with two-stage revision. Orthop Surg 2021;13:884-91. [Google Scholar]